The Humbling and Inspiring Tale of the Game That Proved Hitler's Name Is Still Worth at Least A...

The Humbling and Inspiring Tale of the Game That Proved Hitler’s Name Is Still Worth at Least A Million Dollars

by Rob Dubbin

You probably know about Godwin’s Law, which states that as an argument escalates, it becomes more and more likely something will be compared to Hitler. The idea seems almost quaint now, when fascism makes headlines and snakes its way into every political argument, Godwin constantly poking his head into frame with a cardboard cutout of Hitler, waving it around for attention.

Some months ago, I was invited — very excitedly by a game designer I respect — to play a new game, a work-in-progress even, called “Secret Hitler.” If you have played Mafia or Werewolf, it’s a party game like that, where people divide into factions and trade hidden information to expose each other. They’re all games where you can sort of performatively be an asshole to your friends — lie to their faces, manipulate them against their own interests, “evil” type stuff that is mostly okay as long as everyone feels real-world safe.

At the time, I knew Secret Hitler shared a designer with Cards Against Humanity, the game of politically incorrect sentence completion so wildly successful that it spawned a whole cottage industry of large-scale marketing stunts. This very winter, Cards Against Humanity mailed 8 nights of Hanukkah presents to 150,000 customers who’d paid $15 each, including a 1/150,000 share of an original Picasso. Everyone who bought in — I’m one of them — gets to go to a special website and vote on whether the framed sketch is donated to a museum, or laser-cut into 150,000 pieces. However we vote: It’s an impressive feat of logistics, driven by a keen sense of how to manufacture outrage and generate publicity.

Even with this context, the title “Secret Hitler” extended something of an aggressive invitation. It’s endemic to the Mafia/Werewolf game genre that whoever the bad guy is, someone has to pretend to be that person. I’ve never been particularly comfortable getting into the mindset of a secret gangster or werewolf, but next to Hitler they both seem to offer a pretty chill headspace. It almost surprised me how quickly I declined to play this game, leaving the party pretty much in that same sequence of motions. Then I forgot about it.

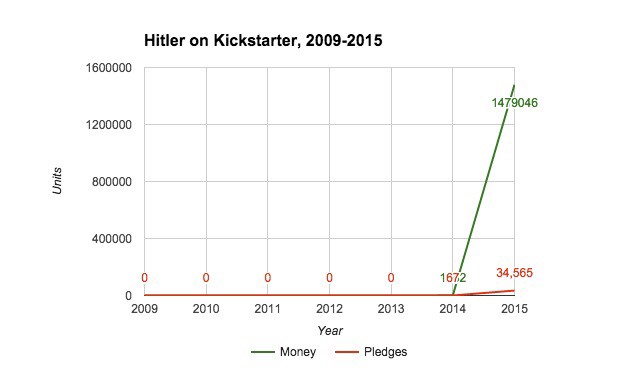

…Until a month ago, when Secret Hitler launched a crowd-funding campaign. Its goal was $54,000, but it crossed the finish line with nearly $1.5 million in pledges. Which do you think is better, looking at it like the Hitler game got a lot of money, or that it got a lot of pledges? Either way, 2015 was a banner year for Hitler on Kickstarter:

(Note the massive year-to-year increase over 2014’s successfully funded “Killing Hitler With Praise And Fire Choose Your Own Path”)

Did you know the Nazis had a style guide? All kinds of stuff in there: logos, uniform standards, just some really tight overall branding. Typefaces. It’s all done up in this kind of angular, Teutonic lettering that makes a goddamn heck of an impact. It lives here, and I understand if that’s not something you want to click on or experience. For me, it helps that I can’t read German.

You could also check out some dope Nazi typography on the Secret Hitler Kickstarter page, where it’s everywhere. In the campaign intro video, on the cards, and all over the page as pre-rendered images, because I guess modern browsers don’t ship with Reich-standard fonts. You’re not gonna lose me just for using these symbols, I’m all for evoking a time and a place. But they printed endorsements with it! If I had tested this game, and in good faith given its designers a positive blurb, and they printed it in the Nazi font on their website — well, did you do that? If so, how do you feel about it?

I’m not a prude about using Hitler’s name. I believe it should be known. But I also believe his name has power, and have consistently felt an immediate wrongness around how Secret Hitler has deployed it. There should be a high bar for invoking this person, and there should be such a thing as falling well short of it. I wonder if someone walked into a US Trademark office and sheepishly filed these papers.

The people who made Secret Hitler advertise it as a playable psychological model of how totalitarianism takes root. Their sales pitch also reassures that the game “doesn’t model the specifics of German parliamentary politics.” Which makes sense: just as all art must draw some line around reality, so did Secret Hitler’s designers pick and choose from the horrific totality of actual-Hitler’s work, isolating just the right parts to weave into their party game. You don’t want to bum people out with this stuff.

Of course, it’s also a laudable goal to want to make people sensitive to fascism, and the dynamics that can help it along. Here are a few to watch out for. One is desensitizing people to fascism’s consequences. Another is to reframe its historic perpetrators as little more than mascots and thematic bunting. A third way to make fascism seem appealing is to demonstrate its remarkable ability to move units. As a game, Secret Hitler claims to be about subverting the mechanisms of tyranny. As a marketing campaign, it seems to rely on emulating them.

At best, Secret Hitler is a clever and enjoyable party game wrapped in a ghastly skein of totalitarian semiotics, with one of the most infamous names of the 20th century attached like a warhead to the title. It’s designed to shock, and obviously with me it succeeded. It’s possible this whole thing just has you thinking “Fuck yeah, Secret Hitler, I know exactly what we’re doing on Ryan’s bachelor weekend now.” The Kickstarter has already concluded in triumph, and Secret Hitler will forever pair with Cards Against Humanity in countless duffel bags.

To be clear, I don’t challenge this game’s existence. Hitler’s agenda targeted every Jew, and so it is every Jew’s birthright to make whatever garbage they want with that legacy. The design team has already taken their shot at the critique that Secret Hitler is gross, announcing a set of stickers that will ship with the game for anyone who’s offended or would like “to pretend that historical figure Adolf Hitler didn’t exist.” So you can rebadge your copy with Trump, or South American Junta Mustache Guy, or Santa Claus. This sweaty attempt to satirize the offended is laced with the anxiety of having committed to doubling down on an aesthetically bad bet.

The deepest irony is not that this game will become a financial success while dwindling ranks of present-day Holocaust survivors tread water at the poverty line. That’s less of an irony and more of a melodramatic truth. The deepest irony is probably that Santa Claus sticker. Because: Could these exact rules have been called “Secret Santa” and tracked a cutthroat St. Nick’s brutal rise to power in a gritty, prewar North Pole? Certainly. Would that have been a better game and a better joke? I say yes. But would it have sold as many copies? Not a chance.

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.