Doomed

One Saturday morning this summer, I was sitting on my couch working on my book. It was early. The windows were open, and I could hear my neighbor and her toddler out in their yard playing and singing. Their voices drifted over in a burbly, companionable way, not too loud, not too soft: “If you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands (clap clap).”

My book’s a novel, and one thread is set in the late nineteenth-century Arctic. That morning I was reading about Robert Peary, the American who claimed to have reached the North Pole in 1909, the first to ever do so. (Peary rejected Frederick Cook’s claims that Cook was the one who made it there first, in 1908.) Now if they ever issued a series of nineteenth-century Polar explorer trading cards (snow-crusted beards, fur hats; think of the profits!) Peary’s card would be the card I least cared to keep. Short version: He was a dick. Still, I had been in a stir of sympathy for him all that week as I read the accounts of his different expeditions — five in all, the first one in 1886 — and sensed how, with each trip, he was growing increasingly desperate and haggard, feeling his chances at glory running out. On one expedition, undertaken when he was forty-two, he traveled for so long and through such intense cold that he lost eight toes to frostbite. EIGHT TOES! Only his little toes were left. He had his feet bandaged up, had his men strap him back to his sledge, and kept going. That is how badly Peary wanted to reach the North Pole.

There’s a part of my brain that can’t experience anything right now — reluctant admiration for a dead explorer, listening to a neighbor and her child playing (if you’re happy… clap clap), exhilarated feelings, sad stripped feelings, whatever — without an accompanying low scampering hum of “what of this can I use for the book, what of this can I use for the book.” I’ve been working on it for three years now, a long time. It’s been a largely good period — I’ve been engrossed, I know myself lucky. Still, it doesn’t escape me that I’ve grown shabby while working on it. The Arctic’s melted and melted some more. The little baby across the street has become a clapping toddler. Sometimes I’ve felt like the entire venture was a terrible, terrible mistake, but we’re — me and it — strapped together now and there’s no going back. Then I think, “Wow, maybe you can use that feeling for the book.”

If you’re frostbitten and you know it, amputate (thunk thunk).

In 1897, a Swede named S.A. Andrée and two companions, Nils Strindberg and Knut Fraenkel, departed in a hydrogen balloon for the North Pole. Their plan went like this: Launch from a specially constructed hangar near Spitsbergen, in Norway; follow favorable air currents to the North Pole; drop a buoy over the pole (written in invisible ink on the side of the buoy: “Sweden waz here! In your face, Norway!”); then float on, possibly to the other side of the world. Maybe they’d descend in Siberia. Or Alaska. Or San Francisco. Who knew how far they might go! Andrée predicted that his balloon, the Eagle, might stay aloft as long as 30 days. As Alec Wilkinson writes in The Ice Balloon, his excellent account of their journey, Andrée packed a tuxedo for the trip, just in case.

The trip’s sponsors included Alfred Nobel and the King of Sweden. Their involvement gave the enterprise some of its air of viability. Andrée’s character also made the plan seem plausible (or plausible-ish). He was not — on the surface at least — either quixotic or romantic. He was an engineer. His day job was in the Stockholm patent office. (His balloon was a marvel of ingenuity and good mechanical design, with a special system of guide ropes and sails that would allow him to steer and a little stove that could be lowered twenty-five feet from the basket so that the men could cook without the balloon exploding.) He’d been to the Arctic once before, as part of Sweden’s delegation for the International Polar Year of 1882, and acquitted himself well there. He believed that hydrogen balloons specifically, and air travel more generally, offered a solution to a problem — how to reach the North Pole — that thus far sledges and ships hadn’t been able to solve.

The words “assured” and “calm” come up in many descriptions of him. Explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson wrote of him, “Andrée was tall, handsome, and modest. The world thought of him as young, although it could, when it wanted to justify its confidence in him, point to his forty-two years.” In the two portraits I’ve seen of him, his face looks as smooth and imperturbable as a balloon’s surface if a balloon ever had an enormous blond mustache.

The forces that drove him — that is, that made him a person fascinated by hot-air balloons and flight, someone who liked to float along the curve of the earth, free from all ties — went mostly un-verbalized, though they must have made themselves felt in person. You can hear some of this animating spark in his recollections of the man, John Wise, who first taught him about aeronautics. Wise had, Andrée wrote, made about four hundred flights in his long life:

He had flown [balloons] in sunshine, rain, snow, thunder showers and hurricanes. He had been stuck on chimneys, smoke stacks, lightning rods, and church spires, and he had been dragged through rivers, lakes, and over garden plots and forests primeval. … The old man himself, however, had always escaped unhurt and counted his experiences as proof of how safe the art of flying really was.

The Eagle’s departure in 1897 was something of a repeat performance. The summer before, the balloon had been brought to this same island near Spitsbergen, unpacked, and inflated with hydrogen. It was ready; the voyagers were ready; the international press was certainly ready. A favorable wind was not. Andrée needed a south wind, steady and not too strong. It never presented itself and the window of travel closed. The balloon was deflated, and Andrée had returned to his work in the patent office to await his next opportunity. Soon after, one of his two companions dropped out of the expedition, announcing in several public spots that he now believed the trip impossible.

In the meanwhile, the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen — feared dead after an absence of three years — had returned from the north: 1. not dead 2. with a new farthest-north record for Norway 3. still gloriously handsome and 4. with a giant sackful of heroic, amazing tales. (This is why the Nansen Polar explorer trading card is always the most popular. What can you do with a rival like that? The fucker was even a great writer.)

All of these incidents — the failed attempt of the year before, his friend’s defection, Nansen’s resurrection — would have been swirling around in the air at the 1897 launch. In Wilkinson’s description of those weeks, everyone sounds tense, snappish. I picture the scene as a few dozen mustached men — engineers, carpenters, journalists, etc. — slinking around the giant, wind-blown balloon house on the water, trying to not trip over ropes and getting in each other’s way as the tethered balloon rattled and rolled around like an impatient spirit. Each day everyone anxiously considered the weather. One day the wind was too blustery. On another, it came from the wrong direction. Finally a day came where conditions looked favorable. Still Andrée hesitated. Strindberg and Fraenkel grew openly impatient. Finally, he relented. They’d go.

It was July 11th. Farewells were made. The three aeronauts got into the basket. The final cables restraining the balloon were cut. The balloon rose. It knocked against something and Andrée was heard to say, “What was that?” Then they were off.

The spectators rushed outside and watched as the balloon dipped toward the water, touched against it, recovered and began to climb its way to the sky. To some of the observers it seemed impossible that it might clear the distant hills but it did.

In an hour, the balloon was nothing but a speck.

The three passengers were never seen alive again.

A brief sidetrack: I’m often struck/amused by how the accounts of Arctic journeys from this period can be seen as mirroring the stages of creative pursuit (minus the frostbite and scurvy). It begins with the person seizing on their plan in a burst of euphoria and optimism. Everything seems possible (“Why, I might even need this tuxedo when my balloon lands!”). This exhilaration is soon mingled with dread and panic. The explorer who has announced to enough people that he’s going to the North Pole will… eventually have to leave for the North Pole. The writer who has told her editor, “Sure, I’ll write that thing” finds… she has to write that thing.

The journey is embarked on. It’s found to be a hundred times more involved and awful than foreseen. Equipment is shed, loads are lightened. Proposed outlines jettisoned. And still the mountains that looked so close that morning end up being far, far away.

Elation gives way to trudging. Trudging gives way to despair.

Even Nansen — glorious, perfect Fridtjof Nansen — was not immune to this. From his book Farthest North: “Here I sit in the still winter night on the drifting ice-floe, and see only stars above me. … Thought follows thought — you pick the whole to pieces, and it seems so small — but high above all towers one form… Why did you take this voyage? … Could I do otherwise? Can the river arrest its course and run up hill? My plan has come to nothing.”

If you’re hungry and you know it, pemmican (chop chop).

The aeronauts’ first night aboard the Eagle was lovely. They skimmed along through the dark, over the clouds. Andrée’s journal entry makes him sound cold but content. When dawn came, the clouds had broken and he could see the surface beneath him. “The snow on the ice a light, dirty yellow across great expanses. The fur of the polar bear has the same colour.”

That day the balloon dropped down to the ice and bumped along the ground. Hydrogen balloons lose height in shadow and fog — fog now enclosed the Eagle. The men threw out whatever they could spare to lighten the load. The balloon didn’t rise but continued to scud along the ice. This eventually made Strindberg motion-sick, which gives a sense of how odd and concussive it must have felt. They continued this lurching, hiccupping progress over the next day. The party sent off carrier pigeons (thirty-six were on board) with messages of their progress. They ate chocolate biscuits and drank ale — this part doesn’t sound too horrible. Having risen in the air, they looked down and saw a polar bear swimming in a channel of water beneath them.

The balloon came down for good on July 14th.

As Wilkinson records in The Ice Balloon, the three had “made the longest flight ever, having been aloft for sixty-five hours and thirty-three minutes…” They’d traveled more than five hundred miles, but because of the zig-zagging of their path this put them “about 300 miles north of where they started, approximately 300 miles from the pole.”

Only one of the carrier pigeons made it back. The message gave their coordinates along with an “All well on board.” A couple buoys later turned up as well. But after 1900, nothing — no word, no Nansen-like return.

For decades the fate of Andrée and his companions was a great mystery. The men’s remains were eventually found, in 1930, in the lee of a cliff on White Island (now called Kvitøya). Strindberg’s body was buried in a cleft between two rocks, giving the impression he’d died first. Andrée’s body was propped against a rock, legs extended, in a pose that made him seem as if he were waiting. Fraenkel’s body lay nearby, frozen under deep ice. Polar bears had torn at both Andrée’s and Strindberg’s bodies.

Their final days are still mysterious in many ways. It’s not known how or exactly when they died. The most convincing theory I’ve seen was advanced by Stefasson in his 1938 book Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic. He posits that Strindberg died in early October, after breaking through the ice while hunting a polar bear. Andrée and Fraenkel, he thinks, may have died soon after from asphyxiation when snow blocked the ventilation pipe of their cooking stove. But this is all conjecture. (Wilkinson gets more into the different theories here.)

Their journals, equipment and Strindberg’s rolls of film were found with the bodies. From these journals and photos it’s possible to piece together their journey across the ice to White Island.

After the balloon landed on the ice, they spent a week transferring its contents onto sledges. These sledges, once packed, weighed hundreds of pounds. The three then started walking back towards land and people, but choosing a route that would allow them to do some exploring along the way.

The ice in the Arctic isn’t smooth — it’s shaggy and ridged and filled with jagged, razor-y bits and hummocks and other obstacles to bark your shins against. There are pools of cold water to slip into (whoopsie-daisy!) as well as leads — or channels — in the ice to clamber across as you attempt to skip from floe to floe. In some places you might have to hack at the ice with an axe to make your way. In others, where the ice is new and thin, you might have to crawl, spreading your weight, so the ice won’t break beneath you.

All of this the men accomplished while also maneuvering sledges that weighed, basically, as much as upright pianos. And a boat! Sometimes they toiled like this for twelve hours a day. Andrée’s journal mentions the ice’s ceaseless “cracking, grinding and din.” It was always churning, night and day, and as the men walked in one direction (southeast), the current beneath the ice was moving them in another (southwest) until they finally gave up and changed course.

The sailors who found their bodies thought the three men had simply died of cold and exhaustion. As one put it, “The cold finished them.” This too seems possible.

The final page of Andrée’s water-damaged journal:

………… …… …… bad weather and we fear ……

………… …… we keep in the tent the whole day

………… …… …… so that we could

………… …… …… …… on the hut.

………… …… …… …… to escape

………… …… …… …… …… like

………… …… …… …… out on the sea

………… crash … …… …… grating

………… …… …… …… … driftwood

………… …… …… …… to move about a little

………… …… …… …… ermits

If a bear tries to eat you, shoot him first (bang bang).

Andrée’s journey is peripheral to the research I’ve been doing for my book. I came across the final journal entries in an anthology, and found them haunting. Another book I read mentioned Andrée in passing, the writer intimating that he’d gone forward with the flight only because he was too cowed to bow out, and this impression stayed with me (even though I no longer think it’s accurate). It’s one thing to float toward the North Pole in a hydrogen balloon having other people think it’s a terrible idea; quite another to be floating along thinking it yourself.

In The Ice Balloon, Wilkinson makes a convincing case that it was likely more complicated that that:

I don’t think he left because he was afraid not to. I think he left because he could no longer imagine not leaving.

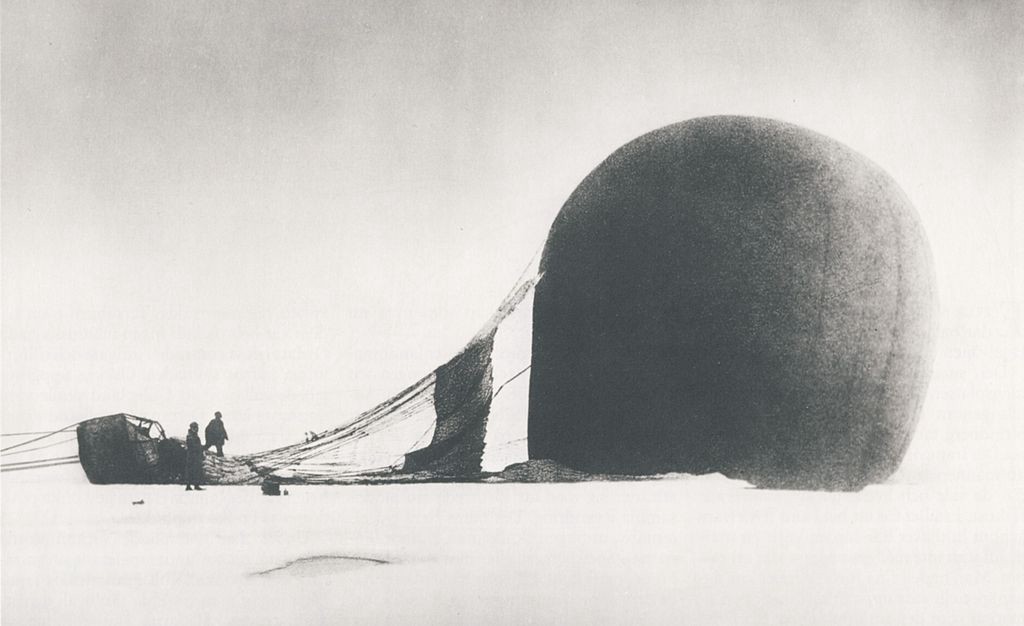

This seems true. So much of what interests me about the Arctic are the ways it’s like life, but with all the motivations and character flaws exaggerated and set against a blank icy-white backdrop, so all the outlines stand out more sharply. Look at that giant grey balloon lying on its side on the snow and ice — that was once someone’s big beautiful doomed irresistible idea. Why did he go? Because it was his idea, and he had to see how well it could do.

Photos courtesy of Grenna Museum/ Andrée Expedition & Polar Centre. All three photos were taken by Nils Strindberg, a member of the Andrée expedition.

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.