What TV Does To Itself

Here is an excellent piece by Emily Nussbaum about “what advertising does to TV” at a time when the two are necessarily clutching each other closer and closer:

Viewers have little control over how any show gets made; TV writers and directors have only a bit more — their roles mingle creativity and management in a way that’s designed to create confusion. Even the experts lack expertise, these days. But I wonder if there’s a way for us to be less comfortable as consumers, to imagine ourselves as the partners not of the advertisers but of the artists — to crave purity, naïve as that may sound. I miss “Mad Men,” that nostalgic meditation on nostalgia. But embedded in its vision was the notion that television writing and copywriting are and should be mirrors, twins. Our comfort with being sold to may look like savvy, but it feels like innocence. There’s something to be said for the emotions that Trow tapped into, disgust and outrage and betrayal — emotions that can be embarrassing but are useful when we’re faced with something ugly.

This is a call to action, almost, but perhaps it’s better read as a eulogy, or as content-creator self-care. “To be less comfortable” with a brand as character or a product as plot is only an option when the two are somehow at odds — if not in practice, then somehow in spirit. And as easy as it is to dismiss the craven CONTENT IS CONTENT people, who are not so much making arguments as they are stating what needs to be true for their businesses or industries to thrive, it’s not clear what we’re really aiming for here. Where is the threshold for an honest transaction between artist and patron and corporation? Surely what animates an argument like this isn’t passion for a particular kind of limited commercial, or for the importance of whatever line product placement allegedly crosses. “Those of us who love TV have won the war” is a statement dependent on what the war was about. To give TV the credit it deserves? For what? For imitating forms politely regarded as less crass or commercial, only to be consumed, shortly, by one considered by the same people to be the crassest of all?

From earlier in the piece:

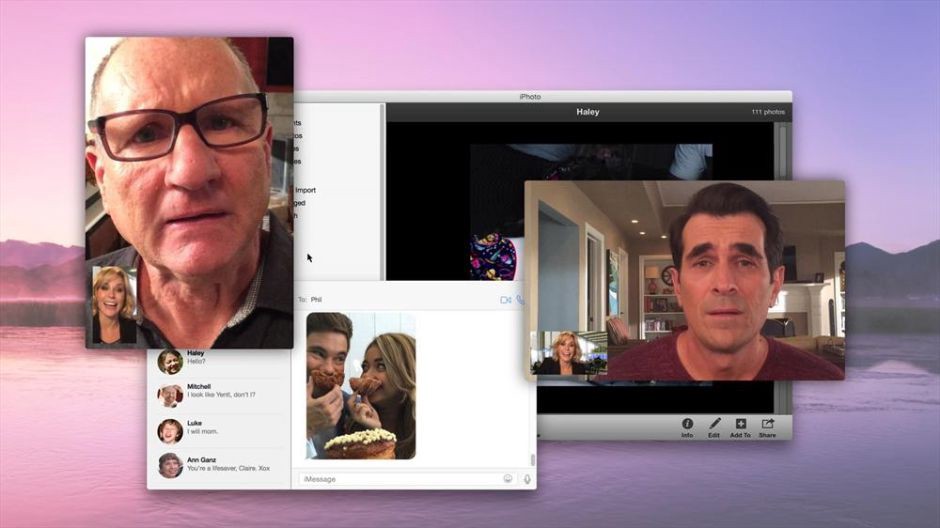

Product integration is a small slice of the advertising budget, but it can take on outsized symbolic importance, as the watermark of a sponsor’s power to alter the story — and it is often impossible to tell whether the mention is paid or not. “The Mindy Project” celebrates Tinder. An episode of “Modern Family” takes place on iPods and iPhones. On the ABC Family drama “The Fosters,” one of the main characters, a vice-principal, talks eagerly about the tablets her school is buying. “Wow, it’s so light!” she says, calling the product by its full name, the “Kindle Paperwhite e-reader,” and listing its useful features. On last year’s most charming début drama, the CW’s “Jane the Virgin,” characters make trips to Target, carry Target bags, and prominently display the logo.

Now, regarding that Modern Family episode, a Qz post from earlier this year:

FaceTime, Messaging, Safari, iTunes, Reminders, iPhoto and even the iCloud all make appearances at one time or another, but non-Apple apps like Facebook, Instagram and Google also get some screen time. The result is an episode that’s incredibly effective and very funny, without ever actually seeming like an ad. In part, that’s because — surprise! — Apple didn’t pay a cent to be involved.

We also learn that a previous episode, which revolved around the acquisition of an iPad, was uncompensated as well. Product placement wasn’t even necessary; but permission was. “Show producers sought out and received Apple’s blessing,” the piece notes. Its headline, presumably not compensated:

Modern Family’s’ Apple-centric episode is product integration at its best — and great TV

Where does a discussion about sanctity or truth or firewalls or checks and balances start, here, concerning this show about a happy family that loves Apple products? (A show you can watch soon after airing on iTunes, or on the Hulu app in your iPhone, iPad or Apple TV, which is available NOW in the Apple iOS App Store — please rate, thank you.)

What is a critic even supposed to ask for? And on behalf of whom? And maybe that’s what the piece is about, ultimately: still not knowing, even during the twilight of an industry, when things should be clearest.