The Robustitude of 'Robust'

by John Patrick Leary

“Tender and Delicate Persons have so many Things to trouble them,” wrote Francis Bacon in 1625, “which more Robust Natures have little Sense of.” Two centuries later, when the New York City minister Thomas de Witt Talmage visited Boston, he was impressed by its people’s robuster natures. “When a mutton chop is swallowed of a Bostonian it gives up,” he wrote in Around the Tea Table, “knowing that there is no need of fighting against such inexorable digestion.” For the women of Boston, it is no longer fashionable to be “delicate.” Instead, Talmage observed, “they are robust in mind and always ready for an argument.”

“Robust” is not often used this way today, to describe bodies and constitutions: now, it is most common as an economic term, almost always accompanied by “growth” or “economy,” or as a way of marketing olive oil, coffee, wine, and tea. It’s a standby in the “creative-class” argot in which “innovation” is the greatest of all virtues. Consider the precious gentrifiers of Philadelphia’s Edward Bok Vocational School, who are building a craft-beer bar and incubator for “Do-It-Yourself (DIY) innovators, artists and entrepreneurs” in a South Philly public school recently shuttered by state budget cuts to the city school district. Bok is a “robust” structure, built to last — or so the WPA workers who built must have thought. Now its sturdy joists and hardwood floors will support “a critical mass of creatives,” which must weigh a lot.

Its overuse in the press and by technology workers has been parodied by a newly coined noun formation, “robustitude” (although some in the tech sector use “robustitude” perfectly earnestly). Penn State’s English department, perhaps anxious that students and parents see a literature degree as professionally weak, describes its curriculum as “robust.” It is a popular political term of art, to describe the “robust debate” that politicians say they welcome, especially when they don’t. For example: when Barack Obama ways he hopes to have a “robust debate” on his Iran policy with Republican rivals, clearly he’d rather not. When Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker signed a law gutting the state government’s open records law, allowing legislators to work in secret, he claimed that the move would promote “robust debate with state agencies and public employees over the merit of policies,” which was obviously the opposite of what it was meant to do.

New York Times, June 16, 1900

In the 19th century (and the first half of the 20th) “robust’s” collocates — the words appearing most often alongside it — were “constitution,” “vigorous,” “ruddy,” “healthy,” and “manly.” “Only robust teachers for Chicago,” declared a New York Times story pinpointing teachers’ “physical weakness” as the public schools’ biggest flaw. “Robust growth,” meanwhile, was a phrase still favored mostly by seed catalogs selling hardy flower bulbs. Imperial British soldiers were often described as “stout and robust,” and military service would make a man out of nearly anyone, even on the losing side. Carlton McCarthy, in his memoir Detailed Minutiae of Soldier Life in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861–1865 — strong title, Carlton — wrote that the experience of Confederate soldiering was fortifying, even in defeat. “Many a weak, puny boy was returned to his parents a robust, healthy, manly man,” he recalled.

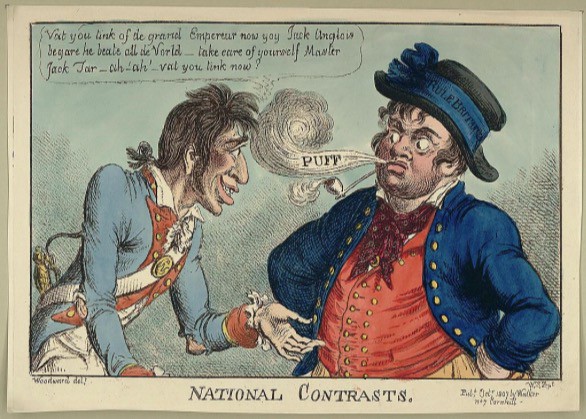

“National Contrasts” (published in London, 1807): A robust Jack Tar blows smoke in the face of a ragged Frenchman in Napoleon’s Army

“Robust” began to be associated with national economies, rather than individual bodies, after World War II; this usage surged in the 1980s, and reached its current popularity in the late 1990s. Ronald Reagan’s economic advisors were fond of the term, invoking it with regularity as the 1982 and 1983 budgets were released amidst a recession.

New York Times, January 4, 1954

Its usage for the U.S. economy seems to track with such moments of economic crisis or uncertainty. Writing of Ronald Reagan’s 1982 budget, US News and World Report wrote that “the President’s advisers predict that a brisk snapback from the recession, beginning in the spring, will launch the economy on several years of robust, uninterrupted growth.” And it is used this way today, as any search of the newspaper or Twitter will show: “Is the US economy sufficiently robust to begin the return to normality?” asks the BBC. “What the US can’t live without is robust economic growth,” said David Axelrod on ABC News in 2010. Or, as @VetsWivesForTrump declares, “We must grow the world’s strongest, most robust economy and cut spending in order to reduce the national debt.” Indeed, its old roots in militarism help explain its popularity among nativists like @VetsWivesForTrump and the popular British neofascist blogger David Vance, who tweets that “if all EU countries followed the robust approach of Hungary, the hordes of Invaders might think twice before seeking to impose themselves.” To stop ISIS, opined a Fox News host, we need a “more robust, manly version of Christianity.”

Wall Street Journal, February 8, 1982

The virile connections endure even for those off the racist right. A robust economy is also often also a “healthy” one. These metaphors treat the economy as a body — a fit, stout paterfamilias that provides for all the nation’s children. Robust growth is equally shared, in the way that a expanding balloon, or Pop’s vigorous pot belly, gets fattest around the middle. Hence the adjective’s common association with “buoyed,” as in “buoyed by robust growth”: the United States would flounder but for its stout, buoyant chum, the economy. The masculine “robust” metaphor raises the question of the gender pay gap, but direct uses of “robust” in connection to women’s wages are comparatively rare. One of the few is a 2014 White House Press release on “the Importance of Ensuring a Robust Tipped Minimum Wage.” Is a “robust” economy necessarily so for women workers? Such questions — of equality, rather than sheer size — may be too delicate for our modern “robustitude” to swallow.

It’s no accident that economic “robustitude” has risen alongside the rise of “lean,” “nimble,” and “agile” as economic buzzwords. Nimble firms require fewer workers, working more, in the service of “growth.” The robust economy is a beast whose inexorable digestion must be fed, preferably by the choice cuts laid off from a nimble, lean corporation. The robust monster is never full.