The 'Real' Steve Jobs

Steve Jobs is a three-act play written by Aaron Sorkin and directed by Danny Boyle, whose facts, such as they are, largely come from Walter Isaacson’s authorized biography of the same name. It is a superbly acted drama, but by far the most dramatic thing about it will be the internet’s reaction when it goes into wide release on October 23rd, because Steve Jobs is less about a product visionary than it is about a deadbeat dad who denies fathering his daughter, grudgingly accepts some culpability in her existence after reaching a low point in his career, then finally achieves resolution with her, which allows him to go on to do some truly great capitalism. All the while, this man is nagged by some haters while preparing PowerPoint presentations to announce some immaculately designed new computers, two of which, according to the film, are total failures.

If there are only two ways to portray Steve Jobs — as a visionary genius whose flaws weren’t really flaws because they were necessary to the practice of his genius, or as a deeply flawed megalomaniac who happened to be a visionary genius (maybe???) — Steve Jobs takes his genius for granted, if only to settle on the latter interpretation. This is the core of why people devoted to his company, his products, and their personal interpretation of his ethos will find Sorkin and Boyle’s film to be deeply offensive — because it inverts their preferred narrative of Steve Jobs and What He Means. (It will be especially offensive to those who, in an attempt to touch Jobs, have patterned themselves after him and decided that they are design or business mavens whose gift to the world is their extraordinary taste; it will feel like a personal attack on their entire mode of being.) To the extent that internet outrage manifests, it will be directly proportional to the success of this movie and its ability to concretize certain elements of Jobs’s public image through the virtuosity of Michael Fassbender’s performance, which is animated less by the man than the icon*.

The structure of the film is aggressively straightforward: It portrays in real-time(ish) a fictionalized account of the moments leading up to the launch events of the Macintosh in 1984 (Act I), the NeXT Computer in 1988 (Act 2), and the iMac in 1998 (Act III). As the film attempts to cram a redemption narrative, a complicated web of interpersonal relations, and more than twenty years of history into a series of backstage scenes at marketing events, it bends time and space greatly to produce an “impressionistic portrait” of Jobs. As Danny Boyle told the Wall Street Journal, “The truth is not necessarily in the facts, it’s in the feel.” And it does seem to feel… right, in many ways? Still, some of the odder results of the time warp include Jobs being aged several years, his hair grayed and his body slimmed down and slipped into his uniform of an Issey Miyake black mock turtleneck and Levi’s 501s at the 1998 iMac launch, the film’s climax, two years ahead of the onstage debut of the personal uniform he wore professionally for the rest of his life*.

Steve Jobs bends people too, but its attempted rehabilitation of former Apple CEO John Sculley, mostly known as the man who forced Steve Jobs out of Apple and led the company down the path that nearly killed it, will probably be called out the hardest. Steve Jobs shoves a backbone up Steve Wozniak’s backside as well — mostly, one suspects, because Seth Rogen can only play one part, which is Seth Rogen — so that he can ask the questions that every Jobs doubter poses: “You’re not an engineer, you’re not a designer… so how come, ten times in a day, I read, ‘Steve Jobs is a genius’? What do you do?” Who’s going to be so mad about that, especially since it has Steve Wozniak’s approval? (Never mind the uneasy parallel between the film, where Jobs suggests that Woz’s public criticism of him was a result of being manipulated, and that in real life, Woz offered his approval of the movie after being paid two hundred thousand dollars.) One can only imagine how the nerds will perceive Kate Winslet as Jobs’s longtime colleague Joanna Hoffman, who functions in the film as Jobs’s consigliere and conscience (and who appears at the iMac launch in the film, even though IRL she had retired by then).

But it cannot be over-stated how much screenwriter Aaron Sorkin is not exaggerating when he says that Lisa Brennan-Jobs is “the heroine of the movie.” For all of the people who show up at product launch after product launch after product launch to dutifully move their story forward — never forget the Apple II! — or to spout an endless stream of Sorkin-tuned quips at Jobs, the film pivots around his relationship with his daughter Lisa, which veers from inhumane to endearingly awkward, and which becomes thoroughly entwined with Jobs’s success as a businesshuman; consumerism abhors deadbeat dads.

It will no doubt be pointed out that while Jobs initially attempted to abandon his first daughter — who, the film did not make clear, did eventually take his name and come to live with him — he was devoted to the family he designed with his second wife, Laurene Powell Jobs, who apparently worked to derail the film, a fact that will be taken on its face to mean that the film is necessarily bad. The messaging to pre-empt the movie on this front has already begun: While Tim Cook’s letter to Apple employees on the third anniversary of Jobs’s death mentions only products and vision, the one released yesterday, for the fourth anniversary, pointedly mentions his family twice:

Steve was a brilliant person, and his priorities were very simple. He loved his family above all, he loved Apple, and he loved the people with whom he worked so closely and achieved so much…. He told me several times in his final years that he hoped to live long enough to see some of the milestones in his children’s lives. I was in his office over the summer with Laurene and their youngest daughter. Messages and drawings from his kids to their father are still there on Steve’s whiteboard.

What will get not a little lost amongst the people who care, above all, about fidelity to their vision of Steve Jobs, is that Steve Jobs is on its own merits, a self-consciously weird movie that goes to extraordinarily lengths to avoid being a generically shaped biopic (and yet…), and that maybe its clearly tenuous connection to reality truly is tangential, and that it will not change the already largely fixed iconography of Jobs, who has been beatified as a tyrant saint in boardrooms throughout corporate America and Silicon Valley, even if it manages to remind people that for a portion of his life he, like most men, was a terrible father.

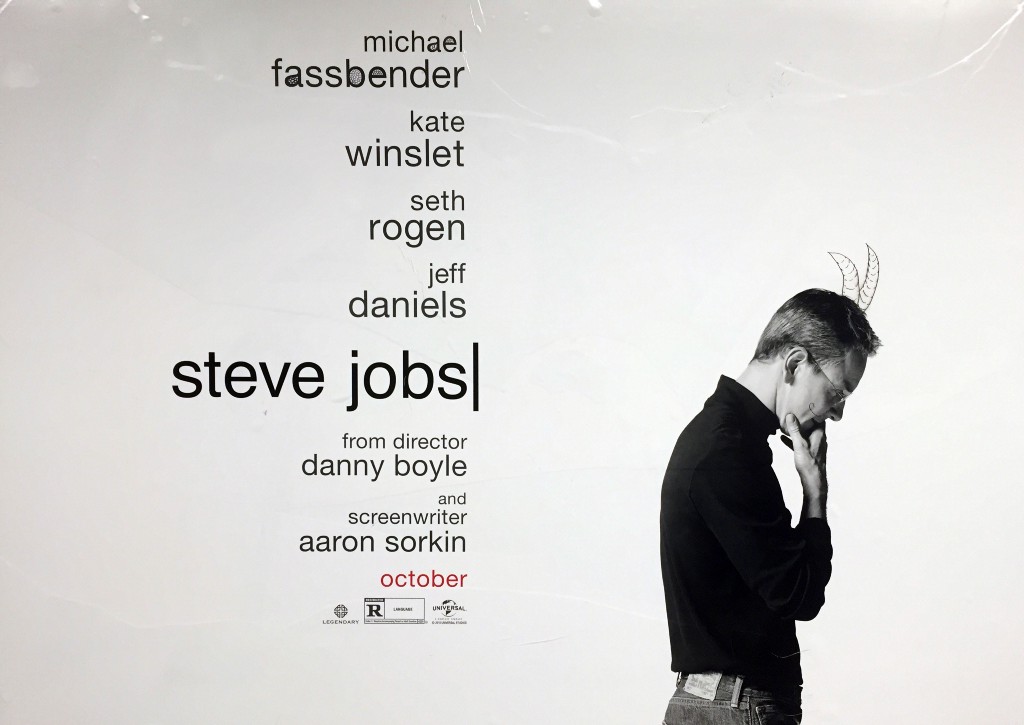

Photo of poster grafitti taken in an NYC subway station

*Given the attitude toward Isaacson’s book in the Apple community (that it fails to capture the Real Steve Jobs, which is to say, the Good Steve Jobs), it is worth pausing to note Andy Hertzfeld’s take on the book: “Steve Jobs got the biography that he wanted and deserved: a best selling, well written, unbiased, comprehensive account of his life and work by the biographer of Einstein and Franklin. As much as he valued simplicity, Steve was a complicated man, full of contradictions, so there’s plenty of room for many different takes on his life and legacy.” I do think it’s fair to say, however, that separate from the issue of whether he properly recorded Steve Jobs’s life, Isaacson didn’t fully grok his subject.

*Although he wore the uniform in Newsweek that year, he wore a suit again when introducing iMovie in late 1999, before wearing the uniform onstage at Macworld San Francisco in January 2000.