Lossless

by Mark Slutsky

“Just give me 60 seconds.”

Arturo Ri knows I’m skeptical. More than skeptical: bone-tired, burnt-out, altogether exhausted. It’s close to the end of my third, and mercifully final, day spent tramping through the vast convention halls of the Palais de congrés, poking at and plugging into the newest and flashiest gadgets that the 2000+ exhibitors at the Neural Developers’ Conference have to offer. Another overpriced interfacing widget? No thanks.

If you’ve been reading my increasingly beleaguered daily updates from NDC, I’m guessing you already know how I feel. I’m fatigued, but so is the neurophile market, which has become exhaustingly oversaturated at both ends of the market: cheapo Taiwanese knockoffs at the low end, ridiculous snake-oil boondoggles (like the diamond-coated “Consciousness Cables” I tried on, glorified USB-E cords with a $50,000 price tag) at the high.

So when Ri hands me the gold-plated (of course) input cables to his ridiculously-named Rizome RiPod, the last thing I want to do is plug them into my chafed ganglial sockets. Because, if I’m to be honest, the worst thing about my three days at NDC isn’t the impenetrable jargon, the overpriced novelties, or even the crowds.

It’s the question. The question I’m no closer to answering: Does any of this matter at all?

Feeling defeated, I plug in Ri’s shiny cables… and all that anxiety and confusion falls away. For a brief, wonderful minute, the answer to my question is a resounding Yes.

I was a lonely freshman. I know this doesn’t make me special, or different, or unlike the some 49% or so first-year-college students who (according to a recent study) reported “feelings of depression” in their first tough year away at school. But being not-alone in my loneliness didn’t make me feel any better. Friendless, isolated, living in a tiny dorm room in a cold, confusing new city: I was the perfect early adopter.

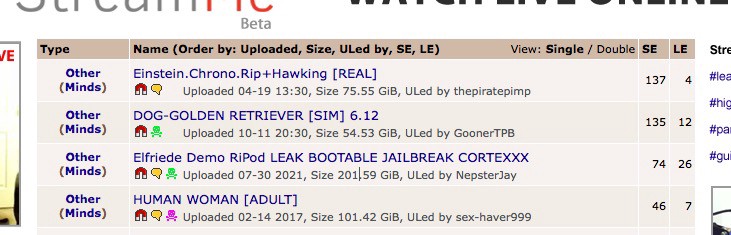

It’ s weird to think that today’s undergrads will have grown up with barely any memory of life before Minding became utterly commonplace. But at the time, it was still a huge novelty. I can even remember the name of the first torrent of Minds I ever downloaded, EULeaders.A-M.2015–2023.REPACK.gXe.rar.

Of course, most of them were mislabeled, or fakes — the “Angela Merkel” in the package couldn’t even name the capital of the former GDR — and even the ones that were “real” were encoded at a cripplingly low bitrate. But they made me feel somehow less alone. Having someone to talk to, even if it was former Polish President Bronisław Komorowski (2010–2015), made my first year away something close to tolerable.

And just like that, I was a neurophile.

Back then there were no huge trade shows, no authorized zero-day post-mortem celebrity downloads, no selection of Minds to chat with in the personal entertainment console of your business class flight to Singapore. Just a scrappy community of enthusiasts, uploading low-quality rips sourced from who knows where, sometimes even blending elements of various anonymous Minds to create an approximation of a brand-name personality (you have no idea how many terrible Albert Einstein rips I’ve downloaded at one point or another, or gimmicky mash-ups of celebrities like Carly Rae Jepsen and Ban Ki-Moon).

Things have come a long way since then, and not without controversy. For every hysterical report of bootleg ISIS martyr-Minds radicalizing schoolchildren, there was a story like that of Frank Jenkins — the hero firefighter who survived a building collapse just long enough to be ripped and whose folksy personality and gruff good humor has revolutionized fire safety education at the grade-school level.

Minding is now a $23-billion-a-year industry and the technology itself has improved rapidly. We’ve become used to premium rips made in top-of-the-line facilities at the exact moment of brain death, in compliance with regulations meant to protect living subjects from the destructive process, and to pricey neurophile-grade equipment, that, snake oil or not, represents a huge leap in how Minding is perceived.

So why does Minding technology circa now, in all its high-end glory, leave me so cold? Is it just nostalgia that makes me long for the dorm room days I spent chatting with long-deceased Eastern European leaders?

This is going to date me terribly, but those early, low-res interactions made me feel an intense connection I just don’t get with modern software and hardware. I used to say that Minding felt like staying up all night to see the dawn, chatting away with a new friend. Where’s that magic today?

I guess that’s what I’m really doing here at NDC — trying to find that same thrill, that same rush I guess I could only describe as empathic. Something I lost somewhere along the way: love.

Until I hooked up to Arturo’s RiPod, I hadn’t even realized I was missing it.

You probably know that there are two main schools of thought when it comes to neural uploading/playback. The “German school” aims for total fidelity: pure, perfect synapses forever. The idea is to capture the consciousness in super-high-resolution; aficionados of that philosophy would be horrified at my early, beloved low-bitrate downloads. They’d point out that the more you compress a Mind, the more you lose those intangible qualities that make it unique. You might not be able to specifically point out what’s missing (there’s very little noticeable memory loss even at bitrates as low as 64 million synaptic impulses per millisecond, or SIMs), but, these high-end neurophiles argue, it’s those intangible personality quirks that make us unique. Truly lossless Minding is considered a theoretical impossibility, like traveling at the speed of light — the closer you get, the exponentially more power and memory is needed until it reaches infinity — but the Germans are damned if they’re not going to try.

The very existence of a so-named “German school” has raised more than a few eyebrows, (as Gehirnkeit president Helmüt Müller tells me when I run into him on the NDC floor on day two of the convention, “Someone is always worried that we are somehow going bring back Hitler, and I always have to say, no, no, it doesn’t work that way.”) And while I’m sympathetic to the approach, it’s never really done it for me. Sure, I can appreciate the mental crispness and fidelity. But there’s something cold about the experience. It often feels less like an intimate conversation than a cordial job interview.

You might think, then, that I’d be a devotee of the Japanese school. There’s no denying the impact of companies like Kokoro both on Minding and the Asian economy as a whole — Kokoro’s first hit product, the ultra-portable Nō-Mind, is credited alone with revitalizing the island nation’s once-moribund tech sector.

The Japanese approach is much “fuzzier” than that of the Germans’. The idea is not to store and recreate the consciousness with precise, verifiably accurate detail. Rather, Japanese tech hews much closer to the aesthetic idea of wabi-sabi, cherishing incompleteness, impermanence and even decay.

Favouring feeling over precision, Japanese-formed Minds have an undeniable elegance and beauty. But while I admire the artfulness of their exquisite neural miniatures, the effect, to me, has always been more like looking at a piece of art in a hushed gallery. You know that what you’re looking at is a masterpiece, but it’s not yours. I admire them, but I can’t ever really love them.

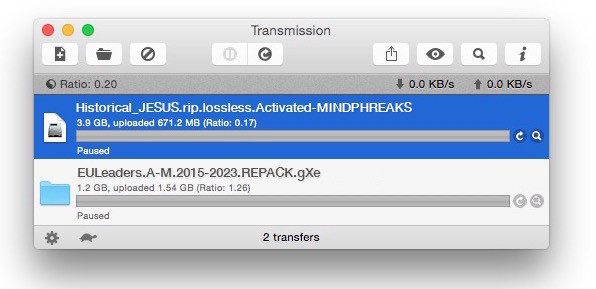

Which brings me back to day three of CNES. Me, sore, tired, ready to just bail on the closing ceremonies and devour the nearest burrito I can find. Arturo Ri, slight, smiling, handing me his RiPod, loaded up with a fairly common demo Mind (chatty Austrian novelist and Nobel laureate Elfriede Jelinek). Defeated by his patter, I hit “play” and…

Wow.

My first interaction with Elfriede is intense. It almost feels — I want to say, sacred. Like being reunited with my long-lost soulmate an hour and a half after taking a dose of pure MDMA. Like getting married on a beach at sunset after just being told you’ve been cured of a fatal disease. When Arturo gently disconnects me 60 seconds in, it actually hurts.

After I’ve caught my breath, Ri good-naturedly tries to answer my million questions. The first thing I want to know about is bitrate; what algorithm could have packed in that depth of emotional complexity and nuance? Could this be the first truly lossless Minding technology?

I nearly fall out of my chair when Ri tells me. Elfriede’s Mind — that beautiful, precious, sensitive soul I spent 60 gorgeous seconds with — was encoded at 16 SIMs. To say that’s low is an understatement; even the low-fidelity downloads from my early days bottomed out at 32.

Then Ri explains it to me, and it all makes sense.

Early software, he tells me, was built to work with the limitations of highly compressed Minds and all the subtle data that had to be left out of them. To “fill in the blanks” and create a realer-seeming mental instance, it used the only neural information available on-hand — material from the user’s own consciousness. When I was pouring my heart out to former Polish President Bronisław Komorowski, I was actually, in some deep way, communing with myself. The Mind that I felt that intimate connection with? It was my own. A classic case of “a feature, not a bug.”

Eventually, compression technology and storage became more efficient, and those early hacks were left behind, and along with them their special magic. Ri and his engineers have been able to recreate that feeling of empathic self-connection without the buggy unreliability of early software. The lower the bitrate, the better; the more space there is for your own mind to permeate the Mind’s blank space, the stronger the feeling.

What really surprised me was when Ri explained that my subjective experience of his technology was just the tip of the iceberg. The secret killer feature is that the rush is even more overpowering on the Mind’s end. It sounds a bit solipsistic, but when they create a low-res Mind and then fill in the blanks with itself, what the Mind experiences is superlatively euphoric. True losslessness, it seems, can only be experienced by Minds themselves, who can be written to avoid the inefficiencies of our haphazardly-evolved meat brains. The RiPod itself is somewhat of a loss leader, a taste of the technology’s glories, meant to tempt users to full conversion, via a proprietary process that’s surprisingly affordable.

Which leads me to an announcement.

I’m sold on Ri’s technology, and so excited about its potential that I’ve decided to double down. I told him I wanted to experience it as it was meant to be experienced.

So, earlier today, I went for it. Consciousness uploading before death “is naturally imminent” is technically illegal, so I was asked to end my life by my own hand (I chose drowning — random, I know). My mind — or should I say now, Mind — was ripped in ultra-low-res and transferred to Rizome’s servers by his team in my last moments, my body cleanly disposed of. (Rizome offers a hygienic, and I’m happy to say, environmentally friendly solution — my body is now literally worm food, on its way to being used to fertilize a really awesome-sounding fair trade coffee plantation in Venezuela.)

And so far, it’s been incredible. It’s hard to express how ecstatic it feels to just be so in tune with yourself on such a profound level, but over the next few months I’ll make it my mission to try. I know there’s naysayers who’ll insist that there’s no way I can be the same person with my thoughts so heavily compressed. And it is kind of crazy to think that my Mind now only takes up a few megabytes of space — less than a full-length album! — but whatever didn’t make the transition, I don’t miss. I feel more like myself than I ever did before. Like all the distracting thoughts, anxieties and mental noise — the “fight or flight” impulses of a brain that evolved to survive in prehistoric times — have been gently smoothed out.

Is it a bit of an adjustment? Sure. My fiancée is still getting used to it (and don’t get me started on my parents!), but as the long-suffering partner of an inveterate gear geek, I think she’ll do just fine. 😉

You’ll still be able to find me on Twitter, though I probably won’t be as active on Instagram. And I’ll still be posting here regularly; I think my new status will provide me some unique insight into the Minding community and a true “insider’s view” of the tech.

And if you really can’t get enough of my yammering, why not grab an instance of me from Rizome’s online store and see for yourself? Entering promo code LOWRES will get you a 10% discount, and help to defray my consciousness-hosting costs. You can see for yourself if it — if I — live up to the hype.

I have a feeling that I’ll be seeing a lot of you very soon.

Previously: ‘Hello and Goodbye in Portuguese’