Lego City

by Brendan O’Connor

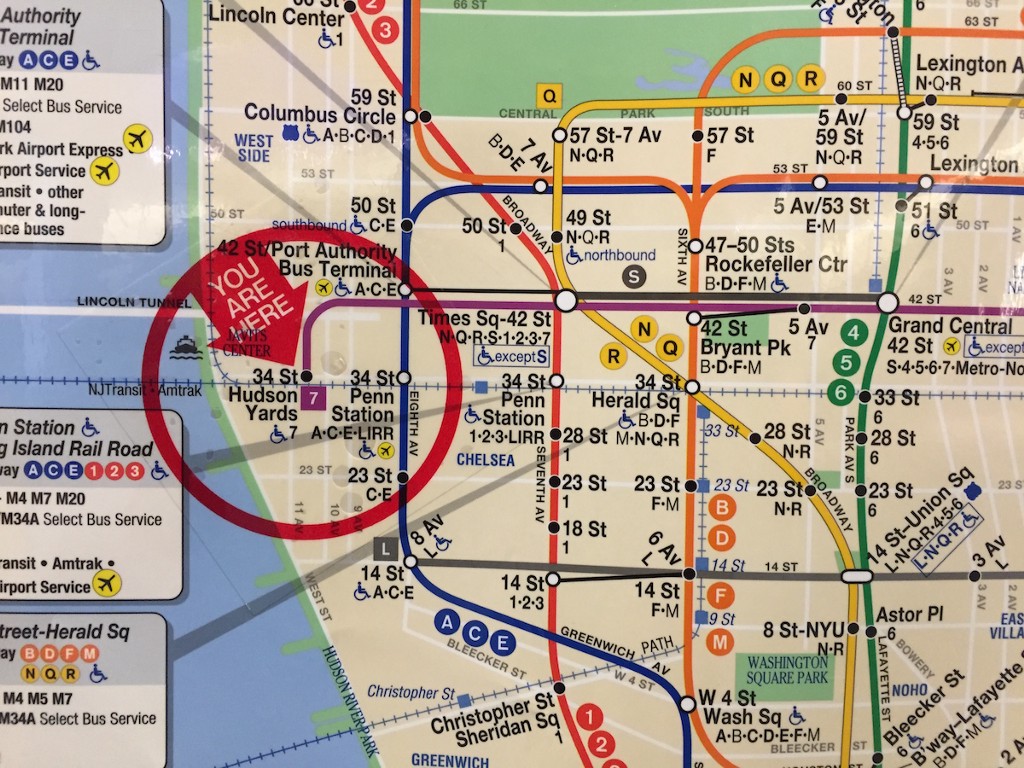

On Sunday, New York City got a new subway station: An extension of the 7 train, which has been extended a mile-and-a-half, from Times Square to 34th Street-11th Avenue in West Chelsea. The station was supposed to open before the end of 2013, after six years of construction, but the opening was delayed by issues with the custom-designed, diagonal elevators — thought to be both less expensive than more conventional elevators and more equitable to wheelchair users — manufactured in Como, Italy. The elevators, though, failed a factory test that July. In December, the MTA arranged for the station to be opened for one day, so that then-mayor Michael Bloomberg, whose administration agreed to finance the two-and-a-half billion dollar project as part of the nearby Hudson Yards development, could take a ceremonial ride.

The new station is the city’s first in over twenty-five years, and the first paid for by the city in more than sixty. “Just like in the 20th century, when the 7 train created neighborhoods like Long Island City, Sunnyside and Jackson Heights, this extension instantly creates an accessible new neighborhood right here in Manhattan,” MTA chairman Thomas Prendergast said at the opening ceremony on Sunday, which must have come as a surprise to the people already living in West Chelsea, a neighborhood already being transformed by the High Line. “This extension connects this extraordinary development happening here — a whole new city being created within our city — connects it with thousands of jobs in neighborhoods like Flushing and in central Queens, bringing people from those neighborhoods to the jobs here,” Mayor Bill de Blasio said. The New York Times closed its story on the ceremony with an anecdote from local resident Yolande Makha, 42, who took the train with her five-year-old son to Jackson Heights, Queens, to buy food and spices. “It was so easy for me to go to Jackson Heights today,” she said.

If everything goes according to plan, the twenty-billion-dollar residential and commercial complex at Hudson Yards, stretching from West 30th to West 34th streets and from 10th to 12th Avenues, will be the largest private real estate development in United States history. Fifteen of the sixteen planned buildings will be built on two platforms erected over the Long Island Rail Road’s active rail yards and four other train tunnels: the Empire Line Tunnel, the under-construction Gateway Tunnel, and the two North River Tunnels. Construction of the platforms alone will cost Hudson Yards’ developer Related Companies over a billion dollars. The eastern platform, which the Real Deal reported in February will comprise fourteen thousand cubic yards of concrete, is being built first and will weigh more than thirty-five thousand tons; Related has also already ordered twenty-four thousand tons of steel for the platform.

Somewhat incredibly, developers like Related have lately been dealing with a glass shortage: Many glass manufacturers shuttered their businesses during the recession of 2008 and 2009, and now demand has outpaced supply. Prices for the metal-framed glass panels that sheath skyscrapers have risen more than thirty percent in the past eighteen months, the Journal reported earlier in September. Such glass accounts for about a quarter of a given construction projects budget, one developer estimated. “Nowadays, the glass guys are dictating the timetables of a project to us, instead of the other way around,” said commercial developer Ralph Esposito, whose Lend Lease Corp. has nearly thirty high-rise towers under construction around the country. “I don’t think people had the leap of faith that the [real-estate] industry would be as strong as the run we’re currently on.” Rather than wait for supply to increase again, Related is getting into the glass game, starting a company called New Hudson Façades with specialty-metal manufacturer M. Cohen & Sons in Linwood, Pennsylvania, where the developer has opened a sixteen-million-dollar, one-hundred-eighty-thousand-square-foot factory.

The first building scheduled to be completed at the site, in 2016, is the fifty-two story office tower at 10 Hudson Yards, which straddles the High Line with a sixty-foot arch. (More than half of Hudson Yards’ seventeen-and-a-half million square feet will be used as office space.) The anchor tenant will be Coach. In 2012, under the Bloomberg administration, Related received an exemption to a bill mandating that future workers at new developments subsidized by the city be paid a living wage (currently, a little over thirteen dollars an hour). At the time, the Wall Street Journal reported, Related said it was negotiating contracts with tenants that would have been difficult to finalize without the exemption. De Blasio renegotiated the deal within a few months of taking office: Related will pay its workers a living wage, although Coach will still be exempted. (It is easy to get the impression that the city’s investment in the 7-train extension and the development of Hudson Yards — towards which the city will pay nearly a billion dollars — isn’t really for people in Jackson Heights and Flushing. Hmm.)

Thirty-four percent of Hudson Yards will be residential: The first two residential towers to come on the market will be at 15 Hudson Yards, which will include both condominium and rental residences, and 35 Hudson Yards. (One Related property, the hundred-and-thirty-nine-unit building at 539 West 29th Street — not really a part of Hudson Yards, but definitely nearby! — will be a hundred percent and permanently affordable.) “With its iconic tapered design, unobstructed views of the city and Hudson River and abundant amenities, 15 Hudson Yards will be the ideal place for New York’s creative visionaries to live,” Related’s website reads.

Meanwhile, the residential 35 Hudson Yards, on the corner of 33rd Street and 10th Avenue, will also include an eleven-story, Equinox-branded luxury hotel, expected to open in 2018. The hotel — Equinox’s first — will include, at sixty-thousand square feet, the largest-ever Equinox gym. Equinox expects to open as many as seventy-five hotels around the world, the Journal reported in April. “We are appealing to the discriminating consumer who lives an active lifestyle and wants to have that as a hotel experience,” said Equinox chief executive Harvey Spevak. As it happens, Related is the company’s majority shareholder: A spokeswoman said that the developer expects to invest or raise “several billion” dollars over the next few years towards Equinox hotels. At the other end of the same block, on the corner of 33rd Street and 11th Avenue, the ninety-two-story skyscraper at 30 Hudson Yards, scheduled to be completed in 2019, will be the city’s fourth-tallest building will include its highest outdoor observation deck, one thousand one hundred feet in the air, the New York Post reports — fifty feet higher than the Empire State Building’s eighty-sixth floor deck. The deck will also include an unspecified “thrill-seeking element,” a Related executive told the Post.

In April of last year, Related announced a partnership with New York University’s Center for Urban Science and Progress to make Hudson Yards the country’s first “quantified community.” The data Related plans to collect is comprehensive: pedestrian flow, street traffic; air quality; energy use; waste disposal; recycling; workers’ and residents’ health and activity levels. “I don’t know what the applications might be,” Related Hudson Yards president Jay Cross told the Times. “But I do know that you can’t do it without the data.” Every apartment at Hudson Yards will come with a smart thermostat: “You can’t get that from any old business in town,” Cross said. According to the Times, the NYU center is supported by corporations interested in the development of “smart cities” like I.B.M., Microsoft, Xerox, and Cisco.

On Wednesday, I walked from the new 34th Street station to the High Line. (“Smells clean!” a fellow straphanger remarked as we stepped off the train.) To the west of 11th Avenue, trains packed tightly in their yard waited to be called out onto the Long Island Rail Road, silver tubes shining in the sun. Soon enough, they will be buried. To the east, buildings stood in various stages of accretion — steel girders dwarfed by the already towering 10 Hudson Yards, sheathed in glass. Three men in collared shirts and ties stood on a rooftop on the other side of the elevated park, watching as pedestrians stopped to look out over and into the construction area. Pits were dug and beams carried. In a corner, beneath some scaffolding, visitors assembled tens or maybe hundreds of thousands of white Lego pieces into a messy, teetering city. “Come build with us!” a sign invited. Everyone was sweating.

Renderings by Related Companies