The Rise of Armchair Marketing

Here is something worth staring in the face:

Burger King sent McDonald’s an open letter proposing that the two fast food chains team up to create a hybrid “McWhopper” burger to celebrate Peace Day on September 21st. Burger King suggested that the “ceasefire” would take place at a single pop-up shop halfway between the corporations’ headquarters, with all proceeds going to the Peace One Day charity.

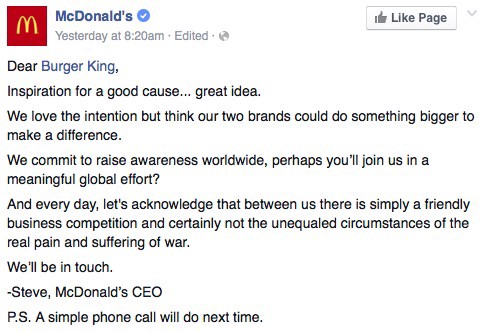

Burger King’s marketing campaign included a video, some social media posts, a special website and full-page ads in the New York Times and Chicago Tribune. In response, McDonald’s posted this on Facebook:

The campaign took the work of “seven agencies,” including David, which helped Burger King create its “Gay Pride Whopper” campaign. (Someone who worked on that project described the process to me, shortly after the ads ran and between drinks at a party so maybe not precisely, as a difficult fight against extensive market research suggesting many of Burger King’s customers would be unhappy with the concept. A large contingent within the company agreed, but were eventually overruled by the company’s fairly new and unusually young CEO, who insisted he saw a major advertising opportunity. Anyway!)

The campaign seems to have been successful in at least one way. It garnered lots of media coverage, most of which adhered to the spirit of the campaign — jokey, but not too jokey, because there’s a charity involved — and which inherited its legitimizing verbs. “McDonald’s politely declines Burger King’s offer of world peace” is the title of the story quoted at the beginning of this post.

Major brands interact, publications produce coverage. Strange? Like basically everything, sure, if you think about it. Unusual? Not at all. It doesn’t demand much of an explanation beyond “these types of things normally do pretty well on Facebook” or “people are going to be talking about this anyway, so we should post about it.”

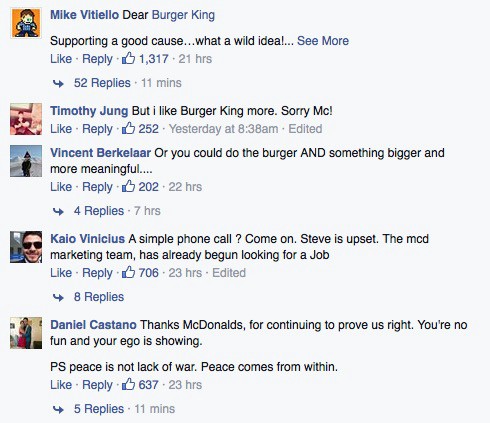

What publications might be missing, however, is just how people are talking about it. The top comments below the McDonald’s post are interesting. They’re not about the stunt, or even about McDonald’s or Burger King.

Some more:

And:

Most notable is the amount of scorekeeping going on: many of the highest-voted comments are criticizing not only McDonald’s as a brand but the company’s brand strategy — these actions are being received earnestly but with a full and demonstrated awareness of their execution as marketing. It’s armchair brand management, expressing interest and concern not just in the company or its products or its marketing, but in the optics of its marketing.

Denny’s joined over the weekend:

This is a brand dream — a vision of a future in which they are dramatically empowered, at least in comparison to the publications they used to depend on for coverage — and a transitional demonstration. Burger King’s placement of an ad in the New York Times led to countless articles in publications, which reached — largely through social media — a great but difficult-to-quantify number of fans, whose reactions would be influenced in part the source of the story; its simultaneous posts on Facebook, which used the Times ad as a mere prop, garnered huge and direct interaction, and ultimately set the venue for the response from McDonald’s. Which prong of this campaign do you think is going to come up in more meetings this year?

That the comments they produced are jarringly straightforward is a triumph of context, and a testament to the power of simplified, streamlined consumption that a front-to-back, top-to-bottom managed system like Facebook can provide. The irritated or confused or cynical comments we might be accustomed to seeing under a typical #brandwar story, even on Facebook, might just be attributable to messiness and noise — people reacting to coverage and aggregation and links rather than to the matter at hand, because they’re seeing something that, really, they don’t much want to see, or they’re seeing something they wanted to see delivered indirectly by an inexplicable middleman with a chip on its shoulder.

Here were have a much simpler hierarchy, and one within which publications — the ones that would have previously noted and recorded brand interactions with, at best, a slight gesture of antagonism — would just be getting in the way, and so are marginalized: Brands, which are verified, are performing on a special stage alongside celebrities and politicians, who are also verified, to an increasingly well-sorted unverified audience that is ready to cheer them on or tear them down within boundaries established by the platform on which they’re engaging. It’s Facebook’s intentional design and structure of authority expressed through human behavior, and it’s translating startlingly well.

In conclusion, congratulations to all brands, forever.