Who Controls Rent Control?

by Brendan O’Connor

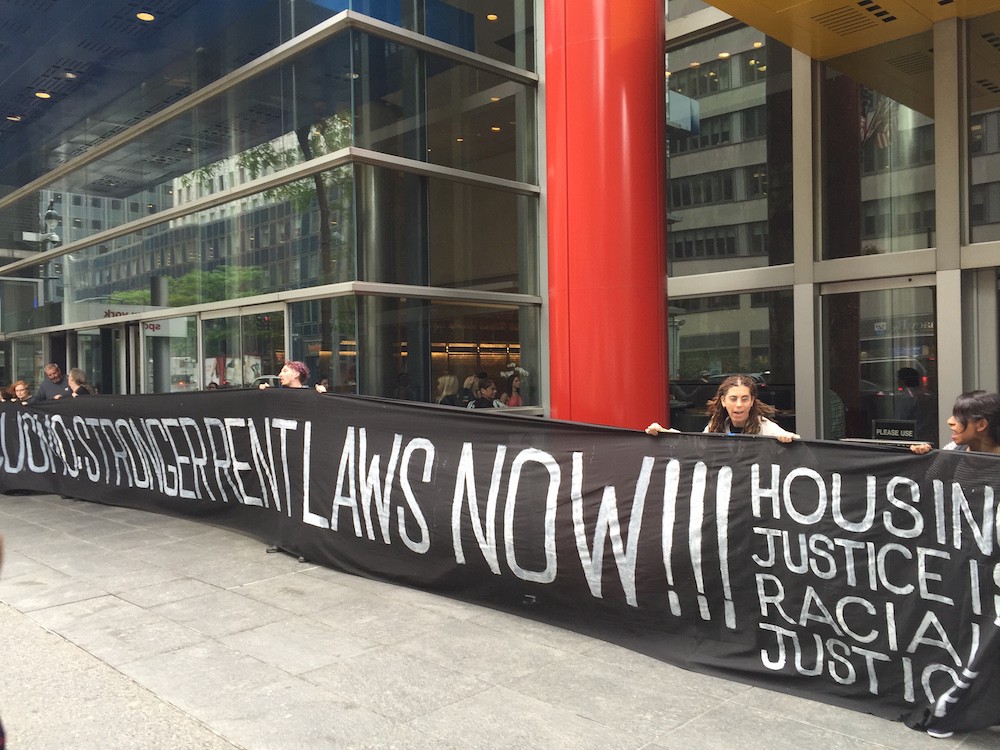

On Thursday morning, seven people were arrested outside Governor Andrew Cuomo’s office in Midtown Manhattan. They were there for a demonstration primarily intended to motivate the governor to strengthen the state’s rent regulation laws, which are set to expire on Monday. There are approximately one million rent-controlled and rent-stabilized apartments in New York City, which house over two million people. If rent regulation laws are allowed to lapse, the city’s already-shrinking stock of those apartments would disappear completely: Landlords would be able to charge market-rate rents once their current leases are up.

In New York City, there are two kinds of rent regulation: rent control and rent stabilization. According to the 2014 Housing and Vacancy Survey, of the city’s 2.2 million rental units, forty-seven percent are rent stabilized and 1.2 percent are rent controlled. “Rent control” is the older of the two programs, and generally applies to apartments in one- or two-family buildings built before 1947. (Rent-controlled apartments can only be bequeathed to family members who were living in the unit for two years before the original tenant vacates it.) “Rent stabilization” generally applies to apartments in buildings, built between 1947 and 1974, comprising six or more units. Both limit the amount by which landlords can increase tenants’ rent when renewing leases; however, rents in rent-regulated apartments can still be increased incrementally over time and eventually, once they hit twenty-five hundred dollars per month — and a tenant vacates the apartment — they become “deregulated,” and can be listed at market prices. (This threshold was raised from two thousand dollars per month in 2011, the last time rent regulation laws were re-negotiated.) This is called vacancy decontrol.

There are other, related loopholes in the laws that landlords can use to deregulate their rent-regulated apartments more quickly. When a landlord makes major capital improvements to a building, or improvements to individual apartments, they can permanently increase rents to cover the cost. (This accelerates the pace at which an apartment is likely to hit the twenty-five-hundred-dollar threshold.) Also, when an apartment vacates, landlords receive a vacancy bonus: They can increase the rent for the next tenant by as much as much as twenty percent.

These loopholes give landlords powerful incentives to harass rent-regulated tenants — who are often elderly — out of their apartments. On Thursday, outside Governor Cuomo’s office, one woman, who went by the name Carmen and has lived since 1997 in a rent-stabilized apartment in Ridgewood, situated along the rapidly gentrifying L-train corridor, told me that her landlord began harassing her after a period of disability. At one point, she left her walker out in her hallway overnight, and he threw it out, she said. He has also cut off the power to her apartment, and threatened to sue her over her service dog. Carmen’s landlord has already raised her rent by three hundred dollars, she said, and he wants her out so he can raise it another thousand.

Until very recently, Governor Cuomo was not understood to be a friend to tenants or their interests. As U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara lay waste to the Albany legislature earlier this year, indicting Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver in January on corruption charges relating to his connections with New York City real estate industry and Senate Leader Dean Skelos in May on corruption charges relating to his connections with the New York City real estate industry, Cuomo suggested that radical renegotiation of the rent-regulation laws would not be appropriate. “Albany is somewhat — has a lot going on right now,” he told the New York Observer in April. Activist groups, frustrated with the governor for not having pushed hard enough for an overhaul in 2011, sensed an opportunity. “Low- and moderate-income tenants who live in more than 1 million rent-regulated apartments are at a breaking point because of the failure of leadership in Albany,” the Alliance for Tenant Power wrote in a letter to the governor later that month. “On your watch, the housing affordability crisis has grown dramatically: entire neighborhoods have been turned into gilded enclaves that cater primarily to infamously wealthy real-estate donors.”

Last weekend, Cuomo wrote an op-ed for the New York Daily News committing to closing all of the aforementioned loopholes. “While the Legislature has it in their hands to negotiate the specifics of the debate, there is one point that is non-negotiable: Their work will not be done unless and until they pass a law to strengthen and extend tenant protections,” he wrote. “I will call them back into session every day if necessary until tenants are protected with new regulations.” The legislative session ends next Wednesday.

Also set to lapse on Monday is the controversial 421-a tax exemption, which is granted to developers who build on underutilized land. (The meaning of this piece of bureaucratic vocabulary does not seem especially fixed.) A developer who is building on unused or underutilized land does not have to pay property taxes for a set period of time — usually between ten and twenty years. If the developer is building a condominium building, the property taxes for the people who buy those condos will be lower; if the developer is building a rental building, the rents will be lower, because the overall expense of building the building was lower (temporarily). “It does produce some affordable housing,” Tom Waters, a housing policy analyst with the New York Community Service Society, told me. “But it’s an expensive way to do it.” According to a study published by NYCSS last month, 421-a costs the city over a billion dollars a year.

Because the price of land in New York City is so high, developers I have spoken to all say that without 421-a or an equivalent program, there is no incentive to build affordable — or even, in some areas, market-rate — housing. “If I didn’t have 421-a, I would concentrate on commercial building,” George Xu, a developer with projects in Long Island City, Flushing, and Bushwick, told me. “We would be very reluctant starting residential projects.” He added, “If there’s less supply, demand goes up, and then rents go up. And that’s no good.” After all, developers are capitalists: They are businesspeople; they’re building buildings because it makes them money, not because housing is a right. (Even if housing is a right.)

However, tenant advocacy groups — like those that gathered outside Cuomo’s office on Thursday morning — suggest that not only is 421-a too generous to developers, but also it functions as a kind of Trojan horse for gentrification and displacement, facilitating the development of buildings that will, in a matter of ten, fifteen, or twenty years ultimately price out a neighborhood’s residents when the tax exemption expires. This, along with weak protections for rent-regulated tenants, has probably done more than anything else to engender the housing crisis that New York City finds itself in today.

Activist groups approved — cautiously, skeptically — of the governor’s position in the Daily News. “What the Governor proposes… are exactly what tenants need,” tenant advocacy coalition Real Rent Reform said in a statement. “Further, given the fact that the current rent laws were negotiated by two individuals who have subsequently been arrested for corruption schemes involving the real estate industry, it is clear that these laws are the product of corruption and cannot be allowed to stand.” (The reference here is to Sheldon Silver and Dean Skelos, who, along with Cuomo, constitute Albany’s three men in a room, a trio which the governor once referred to as “the three amigos.” Of the three, Cuomo is the last man standing — that Bharara may indict him, too, now seems likely.) Tom Waters, the author of the Community Service Society’s report on 421-a, and also of a more recent report that found that rents have risen thirty-two percent citywide since 2002, told me, “There are two things to our advantage: We have a mayor who is strongly aligned with tenants’ rights, and the legislature is embarrassed over the indictments.”

It remains to be seen whether the governor will — or even can — deliver. “Key staff have left, his poll numbers are dropping, and more people are willing to publicly stand up to him,” Ava Farkas, executive director of the Metropolitan Council on Housing, told City Limits. “So in that context, his recent embrace of stronger rent laws is a bold but risky position to take if he’s anything less than serious about making it happen. If he delivers, he’s a hero to millions of tenants and he will have re-established his dominance over Albany. If he fails — especially after so publicly putting his brand on it — it tells that State and the political world that his time as the ultimate power broker is over.” Earlier this week, Capital New York reported that Cuomo was working on a deal that would link strengthening rent regulations with an education tax credit that would incentivize donations to private schools over donations to public schools. Very few people are happy about this, and certainly not anyone outside Cuomo’s office on Thursday. “We have to choose between a place to live and a place to send our kids to school,” one demonstrator said. “Great.”

There, is however, a way forward — and one that would absolve Cuomo of responsibility for enacting policies that might displease landlords. (Among both developers and activists, that 421-a will be renewed in some form seems to be a foregone conclusion — the real estate industry is just too powerful an entity to allow something so beneficial to completely disappear.) If the governor were to call a state of emergency — and what is the housing crisis if not that? — the City Council and mayor could strengthen rent laws themselves, without waiting for Albany to do so. At City Hall on Thursday, Councilman Jumaane Williams asked the governor to do just that. In this way, Williams is calling Cuomo’s bluff: There is, in fact, a straight-forward means to accomplish the end he said he wanted to accomplish in the Daily News piece last weekend; now, we will find out whether that is what the governor really wants after all.

Outside Cuomo’s office, tenants and activists banged pots and pans and stretched a long, black banner across the doors to the building, obstructing people on their way to work. “Governor Cuomo you can’t hide / we know you’re on the landlord’s side,” they chanted. And, “Get up, get down / there’s a housing crisis in this town.” Speaking into a bullhorn, Carmen from Ridgewood implored sleepy commuters to care. “You are just as much at risk,” she said. “If you’re not awake yet, you better wake up.”