Platform Patched

An update on what was once “the fastest growing media site of all time” from Capital New York.

Upworthy, the website that made its name re-packaging heartfelt liberal content for maximum shareability on social media, is shifting its focus to the production of original content, laying off six staffers in the process.

“Three years ago, when we started Upworthy, we hired people to curate and package meaningful videos,” co-founder Eli Pariser in a statement to Capital. (Pariser launched the company with Peter Koechley in 2012.) “But we are now moving decisively to deepen our focus on original storytelling that supports our mission.”

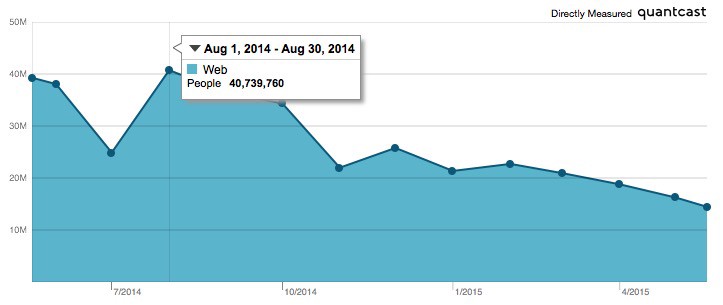

Upworthy is down to about twenty million unique visitors from its peak of about fifty (according to Quantcast). There are a number of ways to explain this, depending on your prior relationship with the site. A fan might say that Facebook has gotten more crowded with both liberal and conservative identity posts, leaving less room for the pioneer of the form. Someone who despises Upworthy’s tone might say that it simply got annoying after a while, or that people got tired of those maddening “curiosity gap” headlines written as if by someone you know, sort of, from high school or maybe work? A founder of the company might refer to “the transition from curation to storytelling” and promise to “decisively to deepen our focus on original storytelling that supports our mission.”

All of these characterizations grant Upworthy — or any pure social site — too much material identity. Here, approximately, is how Upworthy became one of the biggest sites on the internet back in 2012 and 2013: It came up with a way to package preexisting YouTube videos in a way that made them appealing to people who wanted to project certain political and social values to their Facebook friends. This makes sense! Putting a compelling headline and a hard-sell introduction on a video that might have otherwise gotten lost is just good aggregation — the content is free, the payoff is big, and the politics are coherent. What made Upworthy especially explosive was that it was repackaging not just to appeal to people but to a mostly invisible quirk of its distributor — what is sometimes referred to as Facebook’s “long click” metric. Upworthy headlines compelled people to click; long YouTube videos embedded on their site compelled people to stay; Facebook received three very strong signals — clicking, sharing, and time spent — that Upworthy’s content was vigorously engaged with, and treated it as such.

This is how Upworthy, a site that, again, produced primarily video headlines and short captions, became an advocate for using the “attention minutes” metric over page views and unique visitors to measure the success of websites. In early 2014:

We dabbled with pageviews, but that’s a flimsy metric, as anyone who’s suffered through an online slideshow knows (20 pageviews! Zero user satisfaction!).

…

Unique visitors are fine but reward breadth over depth of user experience. Shares per piece of content are quite a valuable signal, but they don’t get you all the way there. And time on site, as Google measures it, works great for e-commerce but is often confusingly broken for media companies.

…

So we decided we needed a new approach. If we’re trying to maximize attention for meaningful content, let’s actually solve for that.

Later that year, in a campaign against “clickbait” in the News Feed, Facebook publicly discussed its feelings about time-on-page.

If people click on an article and spend time reading it, it suggests they clicked through to something valuable. If they click through to a link and then come straight back to Facebook, it suggests that they didn’t find something that they wanted.

So it seemed like they were aligned: platform and content producer, happy and theoretically in sync and producing great numbers for one another. But that was an excessively letter-of-the-metrics interpretation of things. Upworthy was succeeding according to metrics favored by Facebook, but not necessarily by doing the things Facebook believed those metrics would cultivate. A reader might spend five minutes watching a video on Upworthy and leave satisfied, but the site neither created the video nor hosts it — it would have been created by yet another party and hosted on YouTube, a site owned by Google. For Facebook, this is fine but not optimal: Why not just embed the YouTube video directly into News Feed with the same headline and description? Better yet, why not just host the video directly on Facebook?

Facebook-native video took off with the Ice Bucket Challenge, the success of which Facebook summarized in August and later used in explaining its vision for video. Seeing opportunity, publishers started publishing more videos, and more professional videos, as soon as they could. Posts that linked to embedded videos, or even videos that had been embedded on Facebook from YouTube, seemed clunky and less immediate next to Facebook videos that played automatically. Facebook video grew astonishingly fast, and this is what happened to Upworthy:

In one view, early Upworthy was a human-powered apparatus that exploited a temporary glitch (or, at best, intermediate design feature) in Facebook’s platform to grow and, depending on the intentions you ascribe the site’s founders, promote its general cause. It was an extraordinarily weird exercise that will only seem weirder in retrospect; it made sense at the time because it shared an extraordinarily weird context — particular configuration of the Facebook News feed — with the people reading it. A reasonable plan in a situation like that is to use your momentum to raise money and readership while gradually transitioning into something less temporary and contingent, or at least finding a new weird space to fill — the next explosive video-embed-to-website-to-Facebook viral combination. Viral Nova, the most startlingly cynical of its round of viral sites, is performing its slow backwards dance into legitimacy right now.

But platform circumstances can change a little faster than you expect. Sometimes they change in your favor. Other times the company that unilaterally controls those circumstances looks at your success and eventually sees its own failure.