All My Cats Are Dead

by Mikki Halpin

My cat died last month. He had a good life — fifteen long, treat and cuddle-filled years during which he loved parties, burly men, sleeping with his head on mine, eating cardboard — and a good death.

Scientists who study such things say that we should all aim for “compression of mortality” — a long and healthy life, and then you die real fast. You don’t linger, you don’t make any tough decisions; you just live and then you die. My cat did compression of mortality like a champ. He started acting odd, was quickly diagnosed with a serious brain tumor, and went a couple of days later.

It’s hasn’t been that hard to accept that he’s being dead; it’s been hard to accept living without him. I’ve been crying a lot. For the first time in more than twenty years, I don’t have a cat. There is no one excited to see me when I get home, there is no one who will watch BBC period pieces TV with me and think they are having the best time ever, and there is no one whose delight in a piece of string can take my mind off of things. (I’m single!)

Of course, everyone keeps telling me to get a new cat. Or just assumes I will. But no fucking way. No fucking way am I getting another lovable, adorable, cuddly, affectionate, loyal little creature who is in fact a ticking time bomb set to explode my heart into a thousand pieces at some unknown point in the future. (I’m single.)

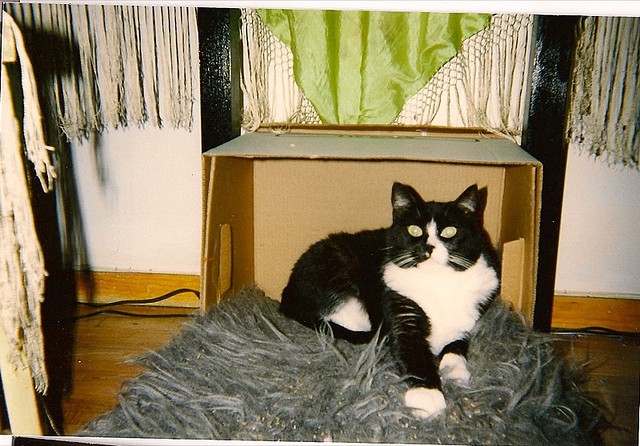

My first cat, Monster, was unplanned. I was going through a breakup — in the nineties, I was always going through a breakup — and had scuttled out of my apartment for errands before going back inside to lie on the couch, watch the OJ Simpson trial, and mull over whether life was worth living. At the hardware store on Santa Monica Boulevard, they had just found a little teeny black and white kitten, who had been pretty horribly abused. She had cuts and what seemed to be burns. She looked like the world had let her down and no one could be trusted; she looked like how I felt. I left my groceries at the hardware store and took her home.

The kitten, who turned out to be a year or two old — she was just tiny for her age — immediately went under the bed. She stayed there for about six months, with the only proof of life being a pair of glowing green eyes staring back whenever I put my head down to check on her or to introduce her to someone. My friend Ron asked if I was sure she wasn’t an owl. I got her out to go to the vet and get a clean bill of health, but otherwise my main contact with Monster was when I lay in bed at night, motionless, until she thought I was asleep: I’d listen to her scurry out to eat her food and use the litterbox before scurrying back under the bed as quickly as possible.

One night, as I was lying there, I felt a little beat of warm breath on the right side of my neck, and a faint purr. She had snuggled her tiny self on my shoulder, trusting and trembling at the same time. I held my breath and didn’t move, and she lasted about two minutes before diving back to her hideaway. (This, of course, is why I named her Monster — what else lives under the bed?)

After that, things progressed slowly, but steadily. Monster’s confidence was measured in inches. First she was ok being on the bed, at night, with me in it. Then she progressed to being on the bed during the day, under the covers, with me in the next room. Eventually we got to the point where I had to get a bigger desk chair to accommodate her on my lap as I worked. She remained terrified of other people — especially men — but gradually grew to rub against their legs and play fetch.

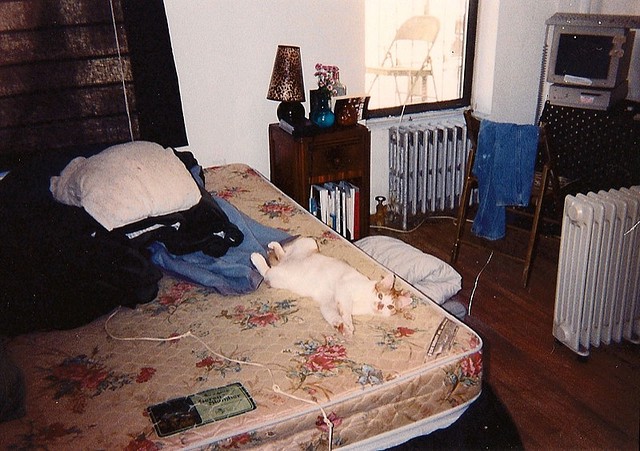

Once, I went to NYC for a week, and while I was gone she had gained several pounds. The vet explained that cats who are afraid of abandonment often overeat in fear that their food supply would dry up. We moved to NY, and settled into a little apartment near Gramercy where we spent the first few nights sleeping on a blanket on the floor. After my stuff arrived, my job started, and for the first time, Monster was home by herself all day, and sometimes at night, because I was going out.I hadn’t really thought about how this might affect her. She became incredibly needy whenever I got home, leaping into my arms, and often forcing me to carry her around like a baby while I cooked dinner or attended to other things. Neighbors who could see into my kitchen through the airshaft reported that she often sat on the windowsill and stared at them mournfully all day.

“She needs a friend,” the vet told me, going so far as to pull out a prescription pad and write “friend” on it, to make it more scientific. I was dubious. Two cats seemed like a lot for one woman in a fairly small apartment. What would potential dates say? Plus, twice as much litter? Twice as much food? What if Monster didn’t like the new cat? What if I didn’t?

A little while later, the vet called, saying he had found two kittens on the way to work, and that I should come in and meet them. They were both orange and white. One was cute, slightly neurotic and shy (a girl) and the other was a not overtly bright but very outgoing (a boy). My heart went out to the girl, but the boy seemed like what Monster and I needed.

Monster and Barrycat (named for his deep bass purr, odd when coming out of a four-pound kitten) fell in love immediately. She raised him and taught him manners, grooming, and all the ways of cats. Barrycat was everything Monster and I were not — carefree, goofy, freely affectionate, and kind of a slut. They slept with their arms around each other and their faces touching and it was beautiful.

One day, when Barrycat was two, I came back from a hike day and found him in a corner, unresponsive. The animal hospital said that he had acute thrombocytopenia, which means that he wasn’t making enough platelets. In cats, the disease is incredibly hard to spot; the damn little stoics will hold on until they get so sick there isn’t much to do. Barrycat died on the operating table when his organs shut down, and the hospital made the mistake of letting me in the room to be with him in his last moments. I ended up covered in his blood, and spent hours in the room they set up for us, morning his stiff little body, wrapped in a towel. I could only kiss his head.

I decided then, no more cats for me. It was the most traumatic thing I had ever been through, more visceral that the death of friends and other tragedies. I was wholly responsible for his little life, and I had not properly taken on that responsibility. Most people didn’t notice what was going on — 9/11 had just happened, I had just gone through another breakup, and I was just trying to carry on — though one a coworker kindly said in the elevator, “I know you are upset, but I haven’t seen you eat in a week.”

Monster suffered even more than I did. She walked around the apartment, looking for Barrycat, crying. She began licking her fur off. She stared at the neighbors again. Dr. Skip gave me the same advice: Get another friend. He even went so far as to suggest getting one who looked like Barrycat, which truly seemed like bullshit.

I went to a few shelters, but just the sight of the cats, and the thought of giving my heart to one made me feel sick. Monster went on Prozac. It helped — she seemed much less distraught, and some of her fur kept growing back. But I couldn’t help thinking about what the vet says. If what she needed was love, shouldn’t I give that to her?

I kept going to various shelters. For the most part I would walk in, then walk back out, crying. My goal in life is to avoid pain, and this seemed to be walking right into it. The fact that this was really for Monster was my way out. I wasn’t getting a new cat — she was.

At the PetSmart in Union Square, I saw a big orange and white kitty who had a bunch of kittens in the cage. The cat was grooming some of the kittens and letting the rest sleep on what looked to be a very comfortable, expansive, soft white belly. I looked closer at the sign on the cage and learned it was a boy named Pepito. I liked the way he was taking care of the kittens. It seemed to be what we needed. “Oh we always put the kittens in with Pepito!” said the volunteer. “He loves them and takes care of them.” Sorry, kittens. I took Pepito home.

I named him Fritz, because he was obviously German, and because meeting him had reminded me of the scene in Little Women where Jo spots Fritz Baer through the keyhole, playing with his nephews. His last name was Newman, because he was … our new man. (Monster’s last name was Halpin. We were a blended family.)

Monster and Fritz were never as close as Barrycat and Monster, because who could be, but they were lifelong buddies, grooming each other and cuddling all day when I was at work. They went through several severe illnesses with me, and a couple of surgeries, where it seemed like I would never get up off my couch and that was fine with them.

Two years ago, round Christmas, Monster got very sick. The vets told me to prepare to say goodbye, and I couldn’t. I could. Not. At that point, she was the longest relationship of my adult life. I had lived with her for more than half of it. I had lived with her longer than I lived with my parents. We had crisscrossed the country twice. We had been through a lot of boyfriends. I rocked her back and forth every night whispering, “Please don’t die. Please don’t die. I’m not ready. I’m not ready.”

She pulled through, much to the surprise of everyone except me. I knew she wouldn’t go until I could handle it. So I set out to treasure the time I had left with her. I worked at home as much as possible. I was already depressed, and reclusive, so I hardly went out, which cost me some friendships but thrilled her to no end. Fritz was her best buddy but I was still the number one light of her universe. I had a bad accident and shattered my ankle, which meant I spent another few months flat on my back on the couch. The cats both took advantage of the human-sized heating pad and the glasses of water I conveniently left around for them to drink out of.

By now, Monster was nineteen. I was on a trip to DC when my cat sitter called to say that she was acting a little strange — hiding, not talking, and not eating. I took the train home immediately, filled with dread but also with a bizarre sense of peace. I was prepared. We went to the hospital, and they said it was her time. I won’t say I wasn’t shaking and crying — I won’t say I’m not crying right now — but I was ready. I held her in my arms, and she put her nose in my neck, just like she did that first night, and she was gone. My heart, and my partner.

Somehow, I was able to get through work. I think it weirded people out. At work, I could pretend she was still at home, mostly. At home, I tried to fathom how Fritz must have been feeling. For most of his life, he had spent twenty-four hours a day with his best friend. Now he was stuck with me and I mostly cried and told him I was sorry.

People kept asking when I was going to get Fritz a friend, but this time I was determined to end the cycle: I would find him another home before another potential heartbreak entered my house. But Fritz seemed to love being an only cat. He was getting on in age, and had never gotten to be the center of attention. Now, if he got the prime seat on my lap while I was reading, he didn’t have to deal with Monster worming her way in to join him. We moved to a much smaller apartment, where a second cat would have been a pretty big inconvenience anyway.

Last month, like I said, Fritz had to leave. He snuggled like a pro until the very end. I couldn’t make it to his cremation, but the cemetery let me send all the amulets and treats that I wanted him to take with him to the afterlife, and promised to tell him that I loved him. His ashes are up on my little altar, next to Monster’s and Barrycat’s

People are already asking when or if I am getting a new cat, and I admit that I have an occasional twinge of loneliness that seems to be particularly cat-shaped. Then time telescopes and I see the inevitable end, another little jar of ashes. Sometimes I joke that if I could find a cat guaranteed to die after I do, I would consider adopting again.

There are upsides, honestly. No more litter. No more cat hair on my clothes. No more cat hair on my friends’ clothes. No more getting sitters when I travel, or rushing home to feed someone. No more chewed-up tulips. And I feel safe now. The unconditional love of a pet is a joy and a weight. They teach us that we can make another being happy just by being ourselves, and that sometimes, for no good reason, love and happiness end. I can take that lesson, and Monster’s, Barrycat’s, and Fritz’s love with me, but I can’t take on another cat.