The Twitter Question

Jay Kang’s tight narrative of “the nation’s first 21st-century civil rights movement” is vital reading:

Since Aug. 9, 2014, when Officer Darren Wilson of the Ferguson Police Department shot and killed Michael Brown, Mckesson and a core group of other activists have built the most formidable American protest movement of the 21st century to date. Their innovation has been to marry the strengths of social media — the swift, morally blunt consensus that can be created by hashtags; the personal connection that a charismatic online persona can make with followers; the broad networks that allow for the easy distribution of documentary photos and videos — with an effort to quickly mobilize protests in each new city where a police shooting occurs.

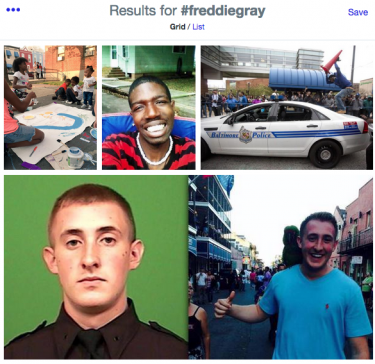

We often think of online activism as a shallow bid for fleeting attention, but the movement that Mckesson is helping to lead has been able to sustain the country’s focus and reach millions of people. Among many black Americans, long accustomed to mistreatment or worse at the hands of the police, the past year has brought on an incalculable sense of anger and despair. For the nation as a whole, we have come to learn the names of the victims — Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Tony Robinson, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray — because the activists have linked their fates together in our minds, despite their separation by many weeks and thousands of miles.

In the process, the movement has managed to activate a sense of red alert around a chronic problem that, until now, has remained mostly invisible outside the communities that suffer from it. Statistics on the subject are notoriously poor, but evidence does not suggest that shootings of black men by police officers have been significantly on the rise. Nevertheless, police killings have become front-page news and a political flash point, entirely because of the sense of emergency that the movement has sustained.

Left unconsidered — in favor of issues like if and how the movement work should through the existing power structures of the current legal and political system — is the vexing question of whether the movement should rely so heavily on Twitter to publicly organize, engage, and spread its message. Twitter isn’t merely a profit-seeking corporation — it’s one that is, of late, in disarray, meaning that with each passing day it grows more beholden to anxious shareholders. The shift toward revenue generation has already produced some profound effects in the shape and flow of the network as it turns inward to more effectively capitalize on its existing users while it desperately attempts to acquire new ones. Beyond the loftier questions of like, what it means for the movement with respect to political economy and the media and whatever, in time, there could be practical consequences for using Twitter to sustain a social movement. If Twitter becomes no longer amenable to these kinds of voices, where can they go next?