The Quantified Baby

Last week, I was sitting on the couch at the end of a long day. I had an itch. I pulled out my phone. I opened my email, nothing new; Instagram, no baby photos to post; I didn’t even bother opening Twitter. “Oh right, Baby Connect,” I said to myself. I opened the app, which I have used to track Zelda’s sleeping and eating since she was just a few months old, and saw its familiar home screen. No recent entries. For three days, I had entered nothing. A new phase of life, one where my daughter’s sleep-wake cycles are quantified only our heads, had begun.

I didn’t come to obsessively tracking her with an app purposefully: It happened, almost, by accident. But I am a controlling, note-taking kind of person, so it shouldn’t surprise anyone that it happened. When I began consciously trying to put my daughter on a sleeping schedule, she was just four weeks old. In the first four weeks of her life, we had rolled with the punches, trying to pretend she was sleeping when we wanted to be asleep, and watching with wonder her capacity for daytime snoozing during all manner of racket. But by the time that month had passed we were exhausted, and having read a book called The Baby Whisperer in desperate moments of lucidity, I decided to try to nudge her toward a more human way of sleeping.

The Baby Whisperer (who is sadly RIP) suggested that the link between a baby’s eating and sleeping were all-important, and that, therefore, the most important thing was to know precisely when they eat and sleep. Doesn’t sound particularly revolutionary, but in the earliest days of parenting, I couldn’t have told you how many times a day my baby ate: Ten? Five hundred? When she cried, we fed her. That often seemed to work but it made for a lot of confusion. The Baby Whisperer claimed that if I knew how often she ate, I would begin to see patterns, and patterns, she went on, were the key to knowing when your baby was tired.

So I did what she suggested: I got a notebook. I began writing down every feeding, every time she went to sleep, and every time she woke up. At the earliest point, based on her age — four or five weeks — the chart in the book said she would probably need to sleep after being awake for an hour and a half. On paper, doing the math was sort of complicated: She woke at eight, needed to sleep again ninety minutes later. But she actually went to sleep seventy-five minutes later. Then she should have slept for an hour-and-a-half, but she actually slept for twenty-six minutes, so… when should she sleep again? In an hour-and-a-half? I still have these notebooks. They are horrific enough that I try not to look at them. One day often took three full pages of calculations, and at times, my husband would say, “This is insane, what are you doing? Why are you trying to force her onto a schedule like this?” And he was right — it seemed nuts. But I wasn’t REALLY forcing her. I was just observing, writing everything down.

Patterns did emerge, and her sleeping and eating started to look more like the chart in the book, until it eventually looked almost EXACTLY like the chart. I also noted that her moods seemed dramatically improved; she stopped crying so much. This was enough encouragement for me.

When Zelda was about four months old, we hired a nanny to come a few days a week. I needed to go to the dentist and the doctor, and I was thinking about working. She was on board with the concept of the baby’s schedule from the moment I met her, which was one of the many, many reasons I liked her so much. Val understood how important Zelda’s “good sleeping” was to me. She understood that I didn’t subscribe to the “never wake a sleeping baby” theory because I wanted her to sleep allllll the way through the night, so I often woke her after she’d been sleeping for just an hour. I showed her the pad of paper where I tracked everything. I tried to explain my, by now, extremely annoying system of marks and symbols.

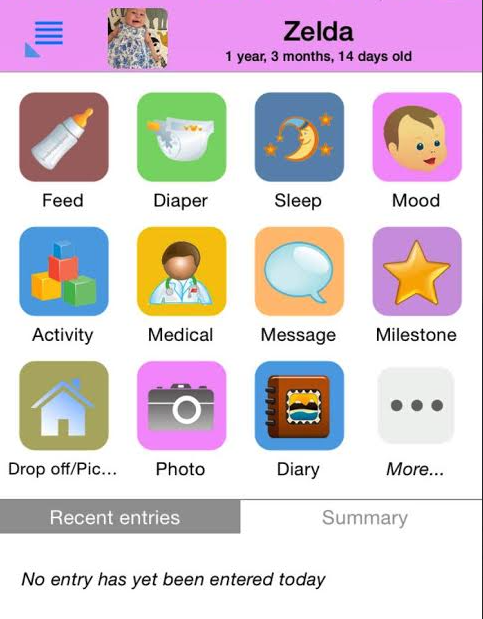

Val suggested, almost immediately, an app she had used with other families: Baby Connect. It tracked everything just as I was doing, but on your phone. I wouldn’t have to add up each nap and nighttime sleep at the beginning of each day (which, in hindsight, definitely seems borderline insane); it would track all that for me. It would also track when she ate, and how much. I said something like, “Okay neat, I’ll check it out,” but inside, I revolted. I was attached to my paper system. A goddamned iPhone app?

I downloaded it anyway. I added myself, and my husband, and Val. Almost immediately, I could see the advantages, despite its clearly lacking design sense and interface. If I wasn’t around, I could open the app and see when she was sleeping, assuming whoever was with her had updated it. But updating it was easy: Open the app, push the button that says “sleeping,” and the timer begins. No more looking at the clock, no more doing the math in my head. “She’s been asleep for forty-seven minutes.”

We switched over to the app easily. I could see how much she’d slept in a day, a week, or a month, in charts or bar graphs. I could see how much she was eating — and back then, when she only “ate” milk, it seemed to matter so much. My life seemed to get easier. And though Zelda was pretty consistent, tracking her variances of a few minutes or an hour each day gave me a sense of control — not over her, but over myself. I could let go, just a little. I didn’t have to do so much math in my head. I could forget exactly when she went to bed, as long as I hit the button on the way out of the door of her room.

It became a reflex, something I didn’t think about. Until I noticed last week, that after almost sixteen months, I’d stopped. I had weaned myself from tracking her food slowly, around her first birthday, as Zelda drank less and less milk and ate more and more food within the general framework of three meals a day. Val and I agreed: It didn’t make much sense anymore to say, “Yes, she had lunch.” Of course she did. But I continued to cling to the sleep tracking, partly because it was still the most volatile day-maker/breaker: If something wakes her up from a nap after forty-five minutes when it usually lasts two or more hours, it’s going to show in her demeanor. So every day, we hit the button at night. We hit it when she woke up in the morning. We hit it again when she went down for, and got up from, first three, then two, and finally now one nap. We tracked all of it. Day in, day out, so that I know how long she slept on my birthday last year — fourteen hours and fifteen minutes; or Josh’s — thirteen hours and forty minutes; or on New Year’s Eve — thirteen hours and sixteen minutes. I know that she slept four hundred and forty hours in both December and January. None of this, in hindsight, is useful. But in the moment, it certainly felt like it was.

In the first year of a baby’s life, there is a lot of talk of milestones. Milestones increase over time in their impressiveness, starting with the almost humorously sad: the first time the baby lifts its head, or rolls over. Then they sit up, crawl, and walk. I didn’t encourage much of anything, and Zelda still seemed to develop generally along the same lines as most other babies — most of the major events happening when I was least expecting them, and least prepared. We rolled with the punches each day, forgetting quickly that just a few weeks ago, she couldn’t hold up her head or wave.

Now I’ve rolled through my own milestone. The itch is gone. I needed desperately to track every moment my daughter slept, until I didn’t. These days, Zelda applauds me when I pick up her toys or wipe off the tray of her high chair: She knows I’m accomplishing something and she wants me to know she thinks I’m doing a good job. I assume (or hope) that if she knew that I was obsessively tracking her sleeping and eating for the past sixteen months but suddenly and without warning went cold turkey one random night last week, she might clap then too.