Friedan's Village

by Marina Budhos

Long before Betty Friedan gave voice to American women’s discontent in her groundbreaking classic, The Feminine Mystique, she was a young mother and wife living in Parkway Village, a tiny, planned garden apartment complex in Queens, New York. This vanguard utopian, international, and interracial community served as her incubator and muse, allowing Friedan to rethink the norm for post-war American families. I grew up there, and though Friedan departed eight years before my family moved in, she was so legendary that I was sure she lived across from me, her parties spilling onto her patio.

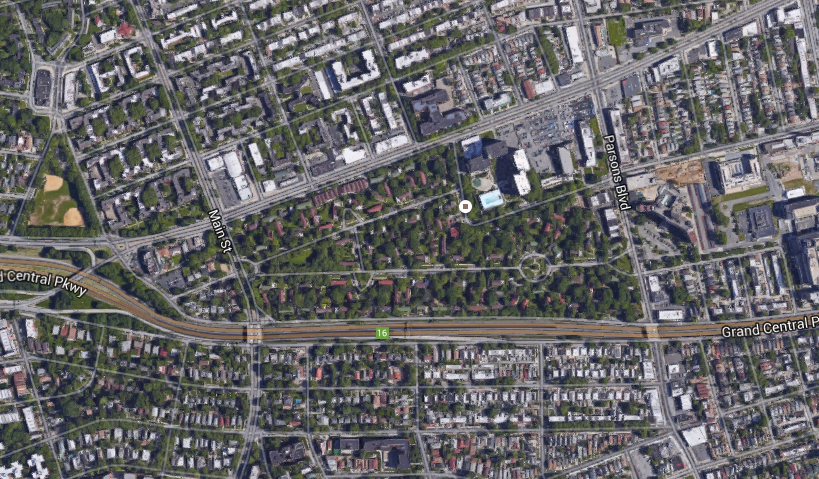

Built after World War II, Parkway Village was the brainchild of Robert Moses: a forty-acre enclave of garden apartments for foreign United Nations employees, many of whom could not find housing because of racial discrimination. Unlike other huge developments that explicitly forbid people of color, such as Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, Parkway Village was open to all races, because no housing for UN employees could violate the UN Charter, which required no “distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.”

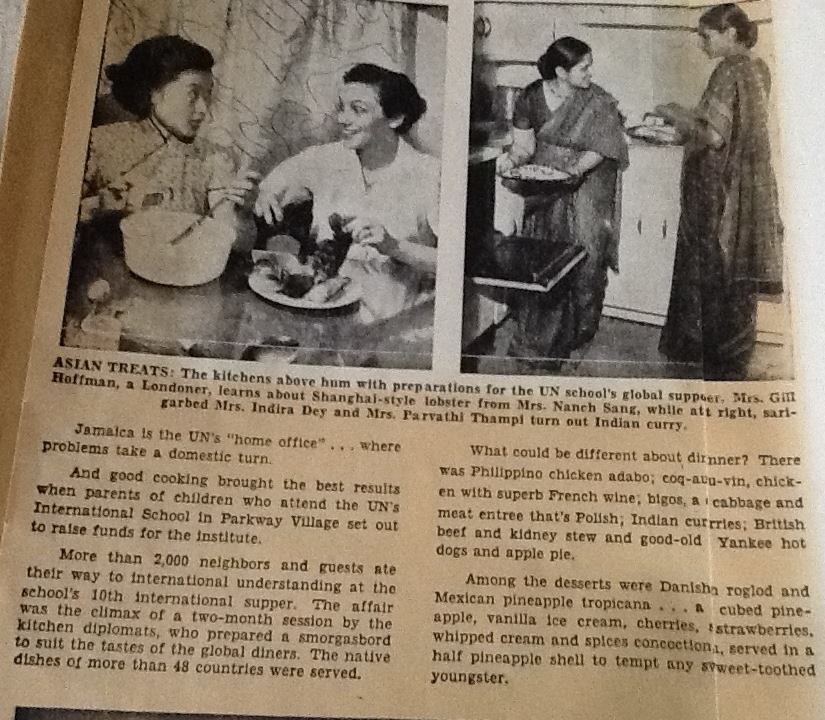

As a result, Parkway blossomed into an oasis of racial integration and international cooperation that was profiled in newspapers and magazines like the New York Times and Collier’s, which characterized it as “living proof” that the ideals of the UN “can work out on Main Street.” Ralph Bunche, the first man of color to win a Nobel Peace Prize lived there, as did Roy Wilkins, head of the NAACP, as well as Babe Ruth’s widow, who was known to give nice tips and hot chocolate to the boys who shoveled her walk. Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Truman came to visit the cooperative nursery school; Paul Robeson’s wife used to show up for parties. The local children were gathered and photographed for the cover of a seminal jazz album, Evolution of the Blues. And Latin American author Ariel Dorfman would remember Parkway Village as an international paradise, before McCarthyism drove his leftist father out of the UN and the country.

Friedan wound up in Parkway because she spotted a notice in a newspaper that the community had apartments for ex-GIs and newspaper correspondents. During a lunch hour at her job, she took the subway out and was so enchanted by the enclave and its spirit of equality that she convinced others to join them, such as Dick Carter, an award-winning journalist who would become the biographer of Jonas Salk. Once in Parkway, through the International Nursery School, their circle would quickly extend to William Jovanovich, the unconventional and daring publisher of Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovich, and Tom Wolf, later vice president at ABC News. These couples — young, liberal, and creative — formed a kind of quasi-commune, sharing meals, creating a babysitting pool, children running in and out of the shared yards. “I loved the concrete daily life of that community … the politics of it, the bonds we formed with other parents at the nursery school,” Friedan wrote in her memoir Life So Far. “We became an extended family for each other, but we also made close friends with Mexican and Iranian families, and French and Swiss we met. All of us were so happy in that community.”

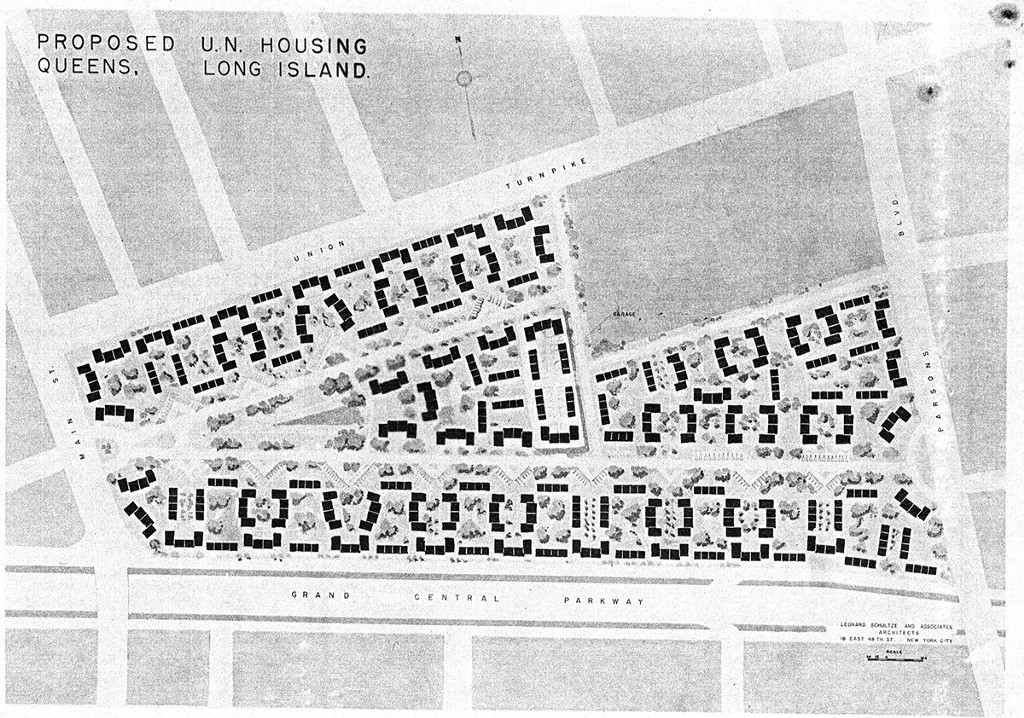

What Friedan experienced was a product of the physical layout of the village, which had been designed by Leonard Schultze and Associates, an architecture firm known for their planning of post-war “cities within cities,” which drew from the tradition of the “garden city” movement in England. Garden cities were seen by urban planners and architects as a way to reinvigorate city living, offering many of the amenities of the suburbs — grassy, open space — while serving a segment of the urban middle class that rejected private home ownership. These were self-contained communities featuring a careful sculpting of the landscape around two-to-three-story buildings that were set within green spaces. Similar communities were built in Queens — Sunnyside Gardens, Jackson Heights, and Forest Hills Gardens — standing in contrast to both the huge, multi-story apartment complexes being built in the city and the individual homes multiplying in suburban Levittowns.

In the village, long apartments opened on to large, shared yards and courtyards and playgrounds, with the complex centered around a large village green. The only place I have ever visited that resembled Parkway was a kibbutz. And while Parkway did not have the extensive communal activities and structures of a kibbutz (though there were lots of organizing activities around playgrounds and international festivals), there was a feeling that every home was everyone’s home. For parents, to live here meant a kind of giving over, as children ran up and down the winding paths, in and out of apartments. When I grew up there, the general rule was that we could roam as far and wide as wanted inside of the village, so long as we came home when the street lamps blinked on. Even then, in the spring and summer evenings, there were so many adult gatherings, that most of us would bolt outside again, comforted by the sound of tinkling and adult voices shifting through the trees.

The most common critique of Friedan and First Wave feminists is that they were really only speaking for white, middle-class, educated stay-at-home housewives, but Friedan’s ideas were first inspired by her interaction in Parkway Village with women from very different backgrounds and countries. During that early period in Parkway, as she developed her brand of feminism, she was not writing from the mainstream center of America, but from a slightly Bohemian vantage which broke down the isolated existence of the housewife, allowing her to stand back to critique American womanhood and begin to imagine other possibilities.

As historian Daniel Horowitz has noted, after being fired from a union news agency when she became pregnant with her second child — a story that was often told by Friedan in later years as a turning point in her developing feminism — she transformed The Villager, Parkway’s local newsletter, into a vigorous outlet, profiling foreign women who offered a different vision of womanhood, working at careers, organizing politically, and knowing how to rely on networks of other women — while making sure their husbands did their share of domestic duties. Of a Filipino resident with six children, Friedan wrote: “American women who find it difficult to combine a career with even one or two children could learn from Mrs. Mendez, who got her children and diplomat husband to do much of the housework.” In another article, Friedan revealed that women from abroad often felt sorry for American women “whose lives were severely restricted by their obligations as homemakers and mothers.” Parkway was the alternative that Friedan glimpsed: not the nuclear family that locked housewives into numbing isolation, but a place of patios and conversation, of women of all nationalities sharing childcare and dishes across the yards.

In 1952, Friedan helped to lead a tenant’s strike, which was sparked by a proposed rent hike that threatened to capsize the community. Friedan and her fellow activists fired off telegrams to President Truman and the presidential candidates; they argued that Parkway Village was an example that could be expanded on a large scale, and that it represented our hope for raising a new generation of children, free from prejudice. Major political figures were enlisted in the fight, including Jacob Javits and Nathan Straus, the former US Commissioner on Housing. The tenants’ fight was covered by many newspapers, and even made it to the New York Times editorial pages, with a plea to save “this living example that the peoples of the world can live harmoniously together.” The group succeeded in a temporary stay, and then the landlords agreed to modified rent increase — sixteen percent, as opposed to the originally proposed thirty-two percent.

In 1956, Friedan and her husband went in search of more space for their growing family. They tried, valiantly, to re-enact the paradise they had found, scheming with Parkway friends and UN officials to buy land up the Hudson to build, as Friedan wrote, their own “truly future-minded cooperative, each with our own houses, a common library, pool, tennis court, as well as a nursery school.” The plan failed, as it “came up against violent opposition,” when local authorities discovered their “dream of a utopian international community” would be interracial.

The Friedans’ eventual home in Rockland County was hardly a faceless suburban subdivision. Set against the rugged bluffs of the Palisades, thirty minutes outside New York City, the Nyack area was also a Bohemian outpost, similar to Parkway Village, with its own storied history of artists and theater and film personalities. (My husband’s parents, Broadway set designers, would eventually build a house there; from their living room, I can see straight down to River Road, where Friedan would eventually pen The Feminine Mystique in a rambling Victorian.) Staying home with three young children, Friedan would regret their decision to leave Parkway — “I felt that I would never again, ever, be so happy as I was living in Queens,” she remarked in It Changed My Life, her personal history of the women’s movement. That ache of frustration and loss would partly impel her later monumental work, The Feminine Mystique. “I realized later that the kinds of community bonds that had sustained our otherwise ‘dysfunctional family’ in Parkway Village … were more important than an extra bedroom and a view of the Hudson River.”

A photo of Marina in Parkway Village, age six

Friedan’s earlier Parkway vision of raising the next generation of children free of prejudice largely came true. My family moved from Hollis, Queens, into Parkway Village in 1964, one year after The Feminist Mystique was published. We had fled a racially homogenous neighborhood, where the police once showed up at our door to report “the black man that was on our lawn” — my father, a dark-skinned Indian immigrant; we took over the apartment from one of the original GI families, who were retiring to Florida. As I was growing up, all over our community, in those airy apartments, mothers enacted Friedan’s revolution: They marched for peace and women’s rights; some pushed integration plans in the public schools, as if to mold our surrounding, neighborhoods into Parkway’s image. (The plan backfired during the tumult of the 1968 teacher’s strike and the racial splits of the time) They went back to school; they started the first women’s center in the borough of Queens; they divorced; they moved elsewhere, started again, and remade their lives.

By the early seventies, the social upheavals that were sweeping the nation crashed right into Parkway, where the counter-culture bloomed — impromptu rock bands playing on the Green, high schoolers holding radical meetings in the basement laundry rooms. But there was an undertow to all this change. Parents separated, were increasingly absent, leaving empty apartments to become havens for lots of risky teenage experimentation. As a private community, we were off-limits to the police, so the Green became an open drug market. Stories of drug overdoses, dropping out, were not uncommon. By the mid-seventies the city was bankrupt, the public schools troubled, and more middle-class families were leaving. A few staunch Parkway Villagers moved out — some to the suburbs, others to a new complex in Manhattan, Waterside Towers, which had opened up next to the United Nations International School.

In the eighties, the complex was converted to a co-op, making it harder to continue that same social cohesion that I experienced growing up. Yet its legacy endures: Friedan’s early motherhood and my childhood in Parkway remind us of a time when cities looked to intentionally engineer middle-class living. That backbone of post-war middle-class rental stock was crucial to the New York City of the fifties and sixties — it kept not just firefighters and nurses and teachers within the city limits, but the creative class, too. Parkway Village stretched that idea further — to racial integration and international cosmopolitanism. Given how racially divided the city during Parkway’s early decades, it was a radical notion. It meant that for children like me, the children of Friedan, the social order looked different than the rest of America; we carried within us a vision of what it might mean to live in a more mixed and equitable world.

All photos — except the final one — courtesy Marina Budhos; diagram via the Parkway Village Historical Society