The Stages of Amazon Grief

The Stages of Amazon Grief

What is Amazon? asks the New York Times.

Clutching her golden trophy with two hands, the creator of “Transparent,” Jill Soloway, thanked both Amazon and Mr. Bezos. Mr. Tambor called the company his “new best friend.”

It was a remarkable moment, considering that only months ago Mr. Bezos and Amazon were being cast as the enemies of American letters. The company’s long-simmering conflict with book publishers over e-book prices had broken out into open warfare, with Amazon going so far as to delay shipments of certain Hachette titles deliberately — a move that invited the collective wrath of the literary world. The host Stephen Colbert directed an obscene gesture at Amazon on national TV.

The juxtaposition says a lot about Amazon’s unusual place in American culture. At the same time that the company was effectively engaged in a book blockade, it was producing what is now an award-winning series that tackles the ambitious subject of transgender people.

And then, not two days later:

Woody Allen is going to write and direct his first television show for Amazon, the studio announced Tuesday morning. The half-hour show has already received a full season order and will be available exclusively on Prime Instant Video in the U.S., U.K. and Germany. Its air date is still undecided.

Here we have an opportunity to avoid a mistake that’s so far been made by every creative industry given option to make it: to engage with Amazon as a conscious cultural force rather than a clear-minded, if sometimes misguided, data-driven financial operation with major but incidental cultural effects. To give credit to Amazon for taking a chance on the excellent Transparent is correct; to characterize that chance as anything but strategic is not. Amazon sees a possible path into the new TV industry through prestige programming, and it has a recent example in Netflix. But it also sees other possible paths, which people tend to ignore: through the soft and nice and star-anchored Alpha House; through its endlessly loopable children’s shows; through the “charming” (and strange! and interesting) Mozart in the Jungle; through a legendary film director who has been publicly accused of the molestation of a child (not to mention its various untapped pilots, which included, among many others, a corny low-budget apocalypse thriller, a musical-comedy series about working at, basically, the Huffington Post, and a Zombieland show).

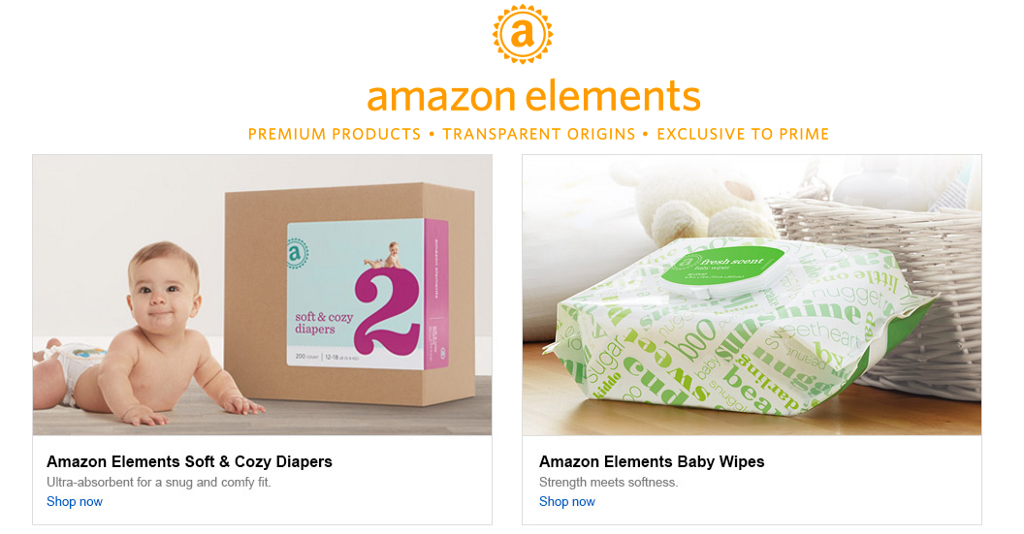

As a cultural effort its TV plan alone is incoherent; but, again, as a set of TV industry plays, it makes some sense. Every new industry Amazon enters gets a fresh expression of its core expansionist vision, rendered in a native-enough vocabulary that has the effect of convincing competitors that Amazon is actually just one of them, which is never true — not in books, not in diapers, not in TV. Electronics retailers, perhaps a less precious bunch, did not muse on the strangeness of Amazon’s choice to sell tablets and jeans and books and soap; it was not necessary to their egos. “Amazon’s place in American culture” is only “unusual” if you believe the company to be, against all prior evidence, something that it’s not.