Free Joan Didion

by Haley Mlotek

All human life is subject to trends, or maybe the more accurate term is “patterns,” but the more I look, the more annoyed I become; where once I would have seen consensus, I now only see cliché. This is what scientists call “aging,” and if I’m correct, it involves a complete and full-body exhaustion towards the things, places, and people that once brought you a kind of compulsive and consuming energy.

But this is also the reason I’m so opposed to the idea of distance, critical or otherwise; I do think we should put our foot down every so often and say something that will no doubt embarrass us in ten years. When people ask me if they should get tattoos, I always say yes; when people ask me if they should write weird, controversial things, I always say yes; if they should dye their hair, accept a job, move to a faraway place, yes. I am an enabler of the highest order, because making these mistakes — tattoos, hair dye, jobs, and writing are all equally terrible mistakes, no exceptions — are the best ways to mark time. “I thought that was a good idea?” is the most powerful statement ever uttered in the history of history.

So I’m curious about the bad decisions we all make, and the ripple effects that occur when enough people of a certain community decide to more or less unanimously embrace a thing, place, or person as the sole representative of humanity’s most intangible qualities: taste, intellect, beauty, and the thing that pervades all of those positive attributes, worthiness. If we are tasteful and smart and beautiful, we maybe, perhaps become worthy of the attention we crave; but how, the community wonders, can we communicate all of those ephemeral ideas inside one physical body or presence?

The answer is Joan Didion. Or at least she’s the answer for a certain type of person, and of course, this being an essay written by a young white woman in her late twenties, I not-so-secretly mean a certain type of me. Joan Didion is a living stereotype and I only mean that in the most literal definition of the term: Joan Didion functions as a mental shortcut. Joan Didion requires very little explanation to a very large group of people, representing a class of consumers who tend to be young, female, upper middle class, white, and somewhat inwardly tortured, a group of people that just so happen overlap with the people who point to the game-changing minimalist chic clothing of Phoebe Philo, current designer of Céline, as evidence of their taste, without actually buying or wearing any of her designs.

The decision to marry these two living shortcuts into an advertisement was a kind of fashion synergy we see maybe once every five years; a time when one cultural arbiter meets another in unexpected and perfect harmony, when two complimentary aesthetics meet in both brands and humans. The image was perfect. The intentions of the brand behind the ad were, I felt, a trolling of the most epic order. There is only a slight difference between “trolling” and “knowing your audience better than they know themselves,” and Céline walks that line perfectly: a case of correlation not being causation. I didn’t feel trolled because Céline was mocking me, or us, but because I had been so thoroughly and effectively target marketed, an experience that is like being a deer in branded headlights. We’ve been seen! I panicked. They know too much!

So what is it that Céline knows about what we know about Joan Didion? I would personally say that we know Joan Didion as a kind of artist who achieved something most people never do in their own lifetime: a fevered, passionate, entirely unexamined fandom that treats Didion and her work as fait accompli, a fact no longer up for debate, or at least not up for debate if you want a seat at a certain table.

The question is not if Joan Didion deserves this praise. Joan Didion is one of the greatest writers Western culture has ever produced or had, and that is, it’s true, not up for debate. She is a writer who makes people buy books; whose name functions as a euphemism for a certain kind of writing style; who has created some of the most pervasive cliches within and about writing. Her legacy is settled: She has become important, definitive, something greater than a single person or article or book can ever be.

In the process of beatifying Didion, we’ve lost our ability to see her as a person and a writer who wrote some things that lots of people think are very good, the end. This is completely anecdotal, but in the last year or so I’ve had numerous conversations with intelligent, reasonable women who have leaned across dimly lit bars to whisper, “I don’t think I like [redacted],” Joan Didion being one of those names, as though this were shameful. The other names included books that “everyone” loved, writers “everyone” read, people who write essays or fiction or biographies or run blogs or edit magazines but who are by means saints or gods, categories of people that you can’t disparage in a normal speaking voice lest a vengeful force throw a lightning bolt right into your heart. “I don’t think I like Knausgaard,” they whisper, as though anyone has ever legitimately enjoyed reading a volume about his struggles.

As a classic enabler, it is my job in these situations to validate this as a worthy choice. But you know what? It is! Not liking Joan Didion is fine. Even not reading Joan Didion is fine. It is the obligatory aspect of this unexamined fandom that rankles me, because we should all do what we want all the time and never apologize for it, and that is only a slight exaggeration.

I mean, I’m guilty of it too. I keep my elected representatives prominently displayed on my coffee tables and bookshelves and all over my tweets and shit just in case anybody forgets that I read Susan Sontag, that I have a pathological obsession with Chris Kraus, as though these signifiers are supposed to tell you something really, really important about me. As though you’re supposed to understand something without me having to say it to you first.

These people are never just people, they’re deliberate choices held up as icons for some purpose greater than their simple existence, and like most things humans do, the act of choosing says much, much more about the choosers than the choices. The act of anointing Joan Didion as our favorite, our best, our everything, is the act that reveals what we’re trying to say: that we’re cool, that we’re educated, that if we are not young and white and slender and well-dressed and disaffected and sad and committed to the art of writing as an arduous and soul-sucking process that must be endured yet Instagrammed simultaneously, then we will be, at least, as close as possible to those identifiers even if it kills us.

Joan Didion, as a writer, is the perfect cipher for the writing process: that mythical time of creation where you are consumed by a painful, wrenching, autonomous urge to lay bare your thoughts, and the resulting sentences are beautiful enough to take away the breath of anyone lucky enough to read them. They remove all oxygen from the writer, leaving only a shell of a woman at her most beautiful: frail, small, weighted down only by a silky dress and nothing as obtrusive as actual human flesh. But it is not, I maintain, Didion’s responsibility to correct this mob mentality. And it is not by any means her fault, despite the opinions of her detractors.

In 1979, Barbara Grizzutti Harrison published her essay railing against Didion, ostensibly — though it seems like an indictment of the people who like Didion more than a critique of Didion herself. “Didion’s ‘style’ is a bag of tricks,” Harrison writes, and then produces a series of sentences parodying Play It As It Lays; she accuses Didion of only ever writing about herself, even when she’s supposed to be reporting on a crime; and at the end, Harrison concludes that “Didion’s heart is cold,” the ultimate crime for a woman.

The whole thing is smart, and well-written, but it reads like Harrison lost a dinner party debate and is listing all the things she wished she had remembered to say when a chorus of friends and colleagues jumped in to defend Didion. For me, the cruelest sentence is the first: “When I am asked why I do not find Joan Didion appealing, I am tempted to answer — not entirely facetiously — that my charity does not naturally extend itself to someone whose lavender love seats match exactly the potted orchids on her mantel, someone who has porcelain elephant end tables, someone who has chosen to burden her daughter with the name Quintana Roo; I am disinclined to find endearing a chronicler of the 1960s who is beset by migraines that can be triggered by her decorator’s having pleated instead of gathered her new dining room curtains.”

This is almost unbearably painful to read for reasons I’m sure Harrison would have me executed for: there I am! Right in that sentence! There’s my Instagram account, with the page of the Sontag journal I’m currently reading held just so you can see my fresh manicure; there’s my collection of zines propped up conspicuously on the dresser in my bedroom, so visitors can see my eclectic taste; there’s my writing, carefully constrained sentences that hint at my mental health issues, my sex life, my recreational drug use, revealing my inherent coolness while pretending to casually conceal it. My sympathies lie with my aesthetics, my possessions, my personality bending to material whims and tasteful trends, and not the other way around.

I once spoke, honestly and without irony, with a friend of mine who maintained a very popular Tumblr account. (LET ME FINISH.) She took submissions and said she was shocked at how often people submitted ads as inspiring fashion content; didn’t they know they were being sold something? Well, yes, I conceded, but — how was that different than an editorial? Aren’t we being sold something then, even if it’s just a myth or feeling as opposed to a literal object?

I would go one step further and say that Vogue — because I suppose all roads do lead to Vogue — sells us something on every page, even if it’s just the idea that Anna Wintour writes her monthly editors’ letter, or that beautiful starlets are gracious hosts to prying journalists, or that a glamorous vacation to an underdeveloped nation is our birthright as Westerners draped in caftans, or that a magazine pushing the aspirational nature of wealth is not always dripping in blood.

It is a sad truth that the prize for living long enough is to see the things and people and artworks that you loved with the pure unfettered abandon of a child taken and mined for commerce, mass distribution, and cynical re-appropriation by brands, in order to be sold back to the next generation as pure, complete, whole elements of beauty and inspiration, but I also mean: who fucking cares. The promise of perfection, of minimalism, of simplicity, is a promise that invites you to discourage with complexity because complexity is the place where you’ll have to decide something for yourself. “Keep it simple” is code for “don’t think about this too hard,” and not thinking too hard is a sedative as powerful as anything pharmaceutical.

What I want, and this is what I want for myself and for all of my fellow sad young literary girls, is to be able to read something without it fundamentally altering how you write or read or talk about the things you like, to invite more nuance and more complexity to everything, to over-examine your likes and dislikes and hold them to the highest scrutiny, until you are the thing that stays still in a turning world of people who can keep themselves still as well.

I suppose here is the place where I should cite everyone’s favorite Didion essay, the one she wrote about a devastating psychological truth not only beautifully but also famously to an exact character count. “The charms that work on others count for nothing in that devastatingly well-lit back alley where one keeps assignations with oneself: no winning smiles will do here, no prettily drawn lists of good intentions,” she solemnly intoned, and I would only humbly add that those charms include the performance of electing a certain shortcut to stand in for the person you want to present to the world; that there is no artist, writer, or person who is entitled to an unexamined and unchallenged love; and that we are ultimately responsible for what Didion reminded us was called character, that there is no image or brand or text that will ever be an effective placeholder for our own personality, no thing that will give you permission to be the person you want to be. No more stories, she wrote, in order to live.

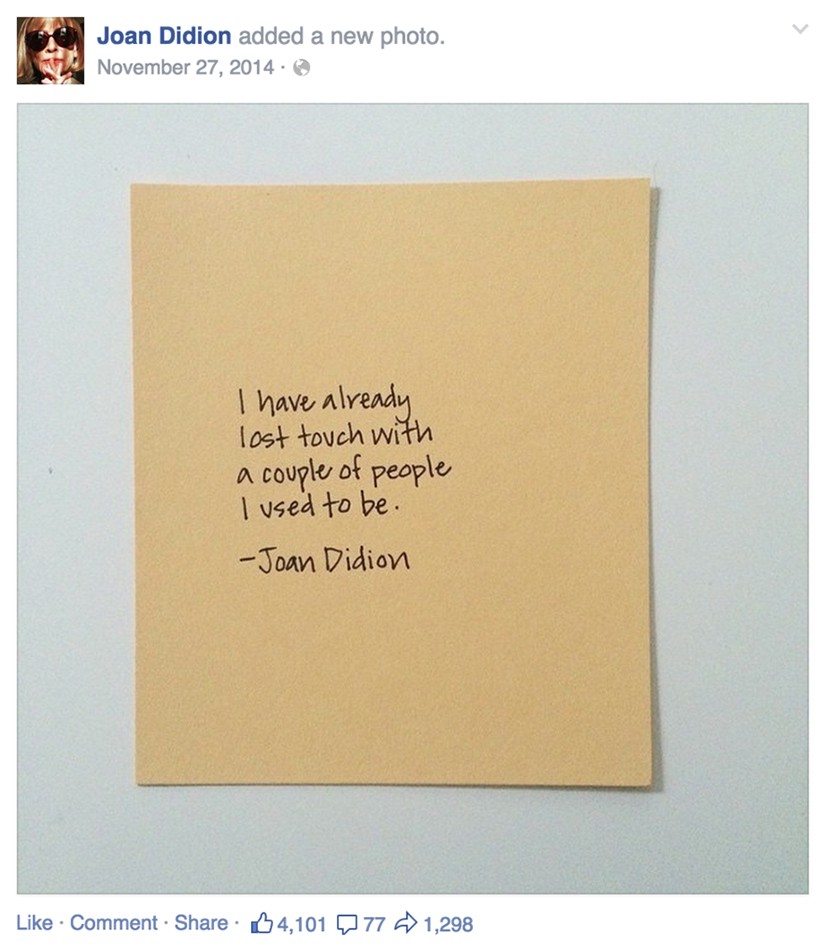

Update: The image above, captured from the official Joan Didion Facebook account, was originally created and posted to Instagram by Kelly Beall.