What I'm Looking Forward To In 2015

I spent more time than was sensible in 2014 waiting for the asteroid. At night, in the dark, unable to sleep, I’d work over every event that was wearing me down, from my own petty problems to the seemingly intractable issues facing the city, the country, the planet, until, unable to find a way out of worry, I would surrender to the comfortable certainty that somewhere out there in space was a giant piece of rock hurtling undetected toward Earth which would suddenly slam into us and put an end to everything. If there were enough time for a further wave of evolution to do its thing before the sun finally closed the books on this solar system, maybe whatever came after would have a better chance of making the world work than I managed to (it all being about me, obviously), but that wouldn’t be my problem one way or the other. It’s an impossibly immature fantasy — everything ends without anyone even having to panic or prepare; no need for reckoning or repentance — but it is not completely impossible, and that tiny thread of plausibility is what I would cling to as I finally managed to drift off.

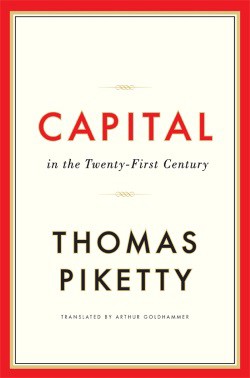

The book of the year was pretty clearly the English translation of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Forget fiction: No one has anything worthwhile to say anymore and even if they did the current custom of churning out memoir-ready observations about life rendered in flat, affectless prose — as if its very lack of adornment weren’t some sort of obvious, in-plain-sight disguise for its essential emptiness — would induce rage if it hadn’t first produced an stultifying sense of exhaustion. No, Piketty’s examination of income inequality and the tendency of power to entrench and extend itself down through the generations was the manual of the moment, and in spite of my deep pessimism concerning our ability to actually make things better for anyone, let alone everyone, I have to admit a small feeling a joy when I think of how many coffee tables, however briefly, hosted this giant slab of capitalist critique. One has to imagine that the poor wretches who work the Amazon factory floor were less entranced each time they scurried up the ladder and lifted down those massive tomes so that another member of the fraternity of man could express his solidarity at 30% off list price plus “free” two-day shipping, but that is surely a detail too churlish to concern oneself with.

Still, as heartening as it was to see the discussion shift even just a little bit in the direction of fairness, I had to laugh each time I heard a central tenet of Piketty’s thesis — that the postwar rise of the middle class was a mere historical anomaly — asserted. As if it all weren’t a historical anomaly. As if we weren’t, in the scale of geologic time, just a small sliver away from sleeping in trees to avoid being eaten by the fierce beasts that roamed below. As if we weren’t smack in between the arrival of the giant asteroid that killed off the dinosaurs and the arrival of the next giant asteroid so clearly overdue.

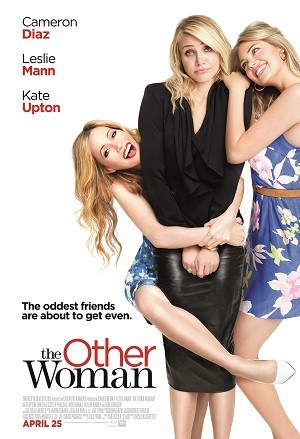

The movie of the year was pretty clearly Nick Cassavetes’ The Other Woman. I should perhaps qualify this by saying that I am in no way the person who should be judging the movie of this or any other year since I am no longer able to spend any time watching a movie, both because of a tragically truncated attention span and the growing conviction that spending two hours in a dark room watching adults play pretend is an inexcusable waste of time (and this comes from someone who will suddenly realize he has spent three hours following the Wikipedia trail of 1970s sitcom stars all the way down to the stubs and write it off as just the cost of having the freedom to open another tab). So I did not see Nick Cassavetes’ The Other Woman (or, for that matter, any other film) this year, but I was unable to avoid its promotional poster, on which the actress Cameron Diaz finds herself wrapped up by her co-stars Leslie Mann and Kate Upton. (Presumably at least one of these three is the titular woman; perhaps they all are. Perhaps the movie is an in-depth examination of the otherness we each occupy at some point; again, I cannot say.) What I found so striking about this image, what stuck with me so strongly that I am here declaring its affiliated product the movie of the year, a work of art that stands as the emblem of its era, is the look on Diaz’s face: She evinces the bemusement borne of the fatigue that comes with existence. It contains sorrow, resignation and perhaps a small amount of recognition of just how absurd our condition is. (Later in the year I saw a still photograph from the Jake Kasdan feature Sex Tape in which Diaz wears an almost identical expression, which may indicate that this is simply one of the basic looks her face makes, but by that point I had spent too much time in my own head developing this theory to abandon it because of the actress’ range, so we’re just going to proceed as if that part never happened.) I resolved to somehow adopt this aspect of her appearance and make it the center of my own emotional register: Sure, everything may be terrible and only getting worse, but what are you going to do? You might as well acknowledge the amusement of the cosmic ridiculousness that provides the background music to which we all go about our business as we wait for our asteroid to come.

But are things really getting worse? I have seen, especially recently, some positive and optimistic assertions that things are not as terrible as they appear and that perhaps the sense of mounting chaos we all seem to feel these days is merely an expression of ego, of an inability to appreciate a more broad historical perspective. This is undoubtedly an admirable view. As someone who believes that the most successful people in our society are those who can completely discard the crippling awareness of how horrible and meaningless almost everything is, those who can actually convince themselves that the things they do are of value to civilization and merit the massive amounts of money and attention (the major metrics by which we keep score) they receive, I can certainly see the upside to being upbeat. If, to choose a random example, the massive amount of self-delusion required to think of yourself as someone who is shattering the paradigm of transportation by providing more opportunities for the well-off to be ferried about by those who are being left so much further behind than previous generations of able-bodied individuals that their only value to the labor pool is as cut-rate chauffeurs is what it takes to get yourself generally acknowledged as the disrupter of the year then certainly the considerably smaller level of wishing it so required to believe that things aren’t getting worse is nothing to begrudge those who don’t want to face the fact that we have already been to the place where it is as good as it’s going to get and not only wasn’t it all that good to begin with, it’s gonna get a whole lot worse before it all ends. And maybe I’m wrong. It happens every day, many times each day, sometimes simultaneous to the very announcement of my most recent important observations. As a fair-minded individual aware of his own frequent fallibility I will not rule out the idea that maybe things are actually getting better. Maybe we aren’t just a bunch of jumped-up monkeys who wander about in a state of want, shuffling around inexorably under the direction of chemicals controlling our every move while we come up with post-facto rationalizations for why our own behavior is justified but everyone else’s is so selfish and inexcusable. Maybe we aren’t simply accidents of time and space but beautiful beings created by a higher power who struggle and stumble but eventually travel in the direction of a transcendent grace which we can’t yet imagine but will someday achieve. It’s possible, I guess. But the more consideration I give it the more I am left with the one simple question that I think best expresses my own hopes and dreams for the future: Where the fuck is my asteroid already? I am anxious, but in my own way optimistic. Surely it will come along soon enough.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.