Voyager

by Alice Bolin

It was a strange December night in Greater LA when Hawaiian monsoons blew the storm of a decade to our shores and we remained, simply, confused. With global weirding, all our weather patterns have sprouted prefixes: Superstorm, meet the megadrought, Godzilla v. Mothra. In Los Angeles, a city mostly devoid of weather other than desperate winds in early fall, natural phenomena are often framed as conspiracies to hinder traffic. I took the 10 freeway that night going west, against traffic, so the drive was fast and easy despite the weather.

I was going to Pomona, one of Los Angeles’ formerly stately, currently dusty annexes. You can picture it in the twenties, orange groves tucked against Mount Baldy — the very high, sometimes snow-capped mountain that is visible on a clear day behind downtown Los Angeles, making the metro area seem all the more like a collage of scenery pictures cut from an old issue of Ideals magazine. Pomona is home to the green, sprawling grounds of the Los Angeles County Fair and an old fashioned, brick-road downtown with a large district of antique stores that really hammers the point: here’s how the past holds up.

All this is to say, it was a damp, dreamy night in a dimension neighboring reality. I was in Pomona to see Jenny Lewis and Ryan Adams at the Fox Theater downtown, an art-deco relic from the first days of motion pictures. It was the second time in 2014 that I had seen Lewis in concert, and I am not about to apologize for that. She and her band Rilo Kiley have been my constant musical companions since I was a teenager. They made the sweetest of emo for the emo-est of girls. Lewis closed her set with “With Arms Outstretched” from The Execution of All Things, Rilo Kiley’s beloved 2002 album that is a masterpiece of naïve moping. The nostalgia in the room was palpable. Many of the women around me clutched their hands over their hearts with ardor. But when I stopped singing along and listened, I was surprised to find that Lewis had rearranged the song, transforming its fuzzy indie vocals to gospel harmonies, swelling to an a cappella finale. “Damn,” I thought, looking at Lewis in her white airbrushed leisure suit, thirty-eight years old now and singing a song she wrote when she was twenty-six. “She sounds better than ever.”

I was made aware looking around the crowd that night that I was part of a generation: teenagers who were listening to sad music in 2002. These were the exact people who would be in the crowd in twenty-five years when Lewis and Adams mount their grandparent rock tour of the nation’s minor league baseball stadiums. As a fourteen year old in Idaho, I wore out Adams’ 2001 album Gold, a folky, alt-country easy listening pop record with lyrics designed to make a fourteen-year-old feel deep. It prompted me to look up “La Cienega” in a Spanish-English dictionary, with no luck.

In tenth grade, we had an assignment to bring in song lyrics we thought could pass as poetry, and I brought in Adams’ “Sylvia Plath.” I hold that story in my heart because I became a grown-up poet; yes, I should have just read Sylvia herself. But it seems like my urge in bringing in the song was the same as Adams’ in writing it: to flatter myself by identifying with a temperamental genius. Adams is known for being prickly and unpredictable, because of incidents like kicking an audience member out of a gig for yelling “Summer of ’69!” Adams still has a reputation as a huge dick, but at the show in Pomona, he seemed more cranky than volatile. After growing impatient with people calling out requests for songs, he said, “I know this sounds crazy, but we actually talked about this beforehand, and we decided what songs we’re going to play.”

Adams is forty now, and he has mellowed into more of a regular dude, not a tortured artiste. He was diagnosed with Meniere’s disease, an inner ear disorder triggered by flashing lights, which has forced him to take better care of himself. “You can’t drink coffee, you can’t smoke cigarettes, you can’t drink alcohol, you need to exercise, you can’t eat salt,” he told Stereogum. “You have to sleep. You’ve gotta get eight hours.” He married Mandy Moore. He started his own record label and recording studio, Pax-Am Records, where he has gotten himself a regular full-time job: he writes, produces, and collaborates there every day from four in the afternoon to midnight. Out of that excess of material he created Ryan Adams, one of the underrated albums of 2014.

In 2011, Adams worked with the Beatles producer Glyn Johns on the subtle, acoustic album Ashes and Fire; Ryan Adams was the guitar album Adams wanted to make when he was producing for himself, and this satisfies me because my greatest vice is comparing music to Tom Petty. There are licks all over Ryan Adams, and it displays Petty and his power pop brethren’s equal commitments to hooks and angst. There are nods to eighties basement rock like on “Kim,” where Adams’ guitar sparkles out of tune across the track. “Nothing’s ever going to be more important to me than the Wipers, Hüsker Du, the Replacements,” Adams said to explain why he made a pure rock record, but he didn’t convince. Ryan Adams hasn’t charted, and critics weren’t that into it either.

“It was at a point in between bands, and having recorded many versions of these songs, I was a bit clueless as to what I wanted it to sound like,” Lewis said of her 2014 album, The Voyager. “I was screaming for a spirit guide, and it showed up in the form of Ryan Adams.” The Voyager has been a triumph for Lewis, her first top ten album and the best work of her career. She direct messaged Adams on Twitter to get his advice on a song, which led to Adams producing the whole album. They recorded it at Pax-Am in a week and a half. Lewis’ earlier solo albums were inconsistent — endearing, corny, and stylistically all over the place. Adams’ guiding hand is evident all over Voyager, which is another guitar album, another homage to late seventies rock, but more groovy than Ryan Adams. Is it a coincidence that Tom Petty had his first number one album in 2014, Hypnotic Eye? I mean, probably.

In Pomona, Adams surprised the audience by covering Lewis’ “She’s Not Me,” a song she had just played a half hour earlier. It’s a standout from The Voyager, a sad song with a thumping beat that sounds — and I mean this in the best possible way — like Hall and Oates. Adams sang it in Lewis’ key too, pointing up what had been obvious the whole night: his voice is remarkably true, much more so than on his records. He is a choirboy and Lewis is a choirgirl and they are both throwing away notes to sound like Tom Petty. And Tom Petty is a choirboy who is throwing away notes to sound like Bob Dylan. Listen to “Fault Lines” from Hypnotic Eye, though. More often now, Petty sings not like Dylan but like their friend George Harrison, in a gentle croon.

Petty, Dylan, and Harrison, along with Jeff Lynne and Roy Orbison, created that most utopian of rock and roll projects, The Traveling Wilburys, a true supergroup who made two albums in the late eighties and early nineties, just, bafflingly, for fun. Lewis covered their song “Handle with Care” on her first solo album Rabbit Fur Coat with her fellow indie cuties Ben Gibbard and Conor Oberst, in acknowledgement that if you are going to sing a Wilburys song, you must invite your most famous friends to sing it with you. All Wilburys songs indulge in wordy rhymes, like on “Handle with Care”: “Been stuck in airports, terrorized/Sent to meetings, hypnotized/Overexposed, commercialized.” See also: Lewis on “The New You” from The Voyager: “You struggle with sobriety/Dreams of notoriety.”

The most notable lyrical references on The Voyager are to eighties heavy metal — Metallica, Slash, and the Headbangers Ball — evoking Lewis’ childhood. The Traveling Wilburys albums were released when Lewis was a teenager, but they are a direct line to the music of the seventies, when Lynne made the Xanadu soundtrack, when Harrison made his solo albums, when Petty made Damn the Torpedoes. And when Lewis was born. Like Adams, Lewis is sadder but wiser in her late thirties, and The Voyager is a more truly vulnerable album than Lewis has ever made — it’s about marriage, compromise, baby envy, and the death of her father. “You’re thirty-nine and looking at your friends and parents are dropping dead and some of them are dropping dead, starting early, it’s a weird time,” Adams told Stereogum. “It’s kind of like that movie The Big Chill but everyone’s wearing Dinosaur Jr. shirts.” It makes sense that at a time in their lives when they are cleaning up and taking stock, Lewis and Adams use their music to reach all the way back. Nostalgia is a search for origins and identity. The Traveling Wilburys were a nostalgic band too, and they weren’t longing for the height of their stardom; they were longing for the music of their childhoods, nineteen sixties car songs and Buddy Holly.

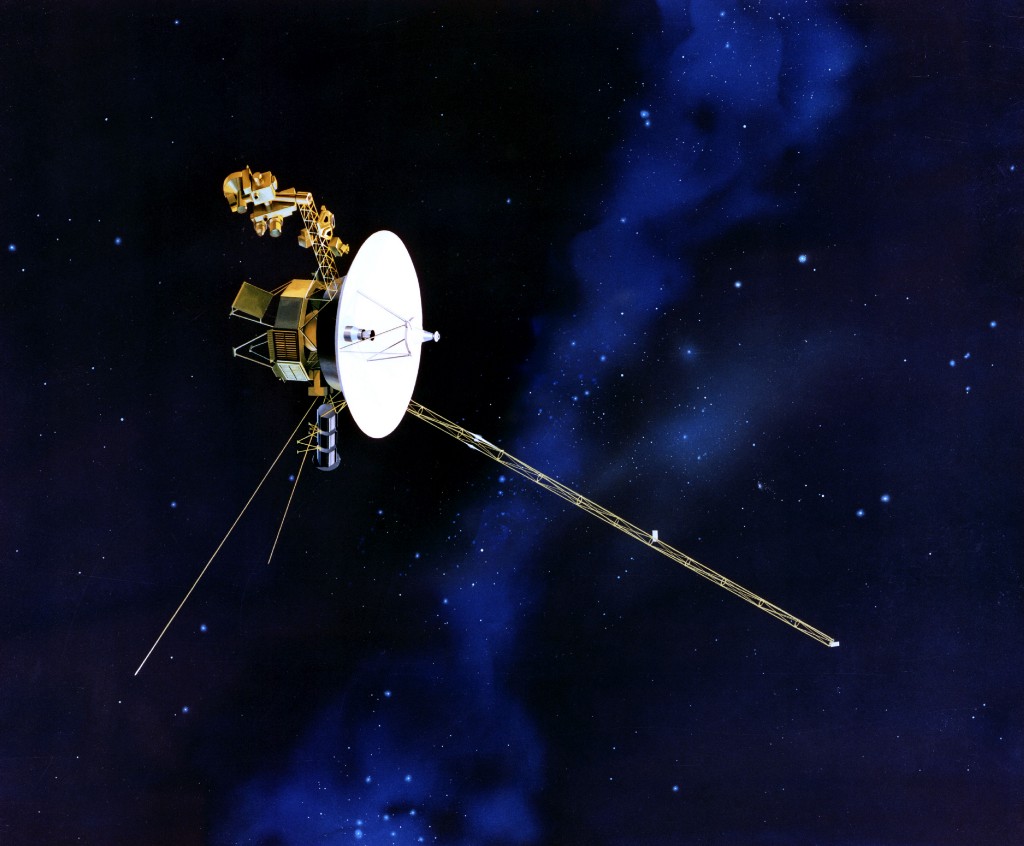

In 1977, the year after Lewis was born, NASA launched its exploratory spacecraft Voyager I, carrying the Golden Record, an artifact intended to communicate the entirety of life on earth to any beings who might encounter it — speaking of utopian projects. In September 2013, NASA announced that the Voyager had broken through the heliopause and entered interstellar space, the first spacecraft ever to do so. “The Voyager’s in every boy and girl,” Lewis sings of the event on the title track of The Voyager. “If you want to get to heaven, get out of this world.” I saw Lewis in Los Angeles in August with my younger brother, and we listened to her play the songs we used to sing along to as teenagers, when I would drive us to Barnes and Noble and Pizza Hut. It was nostalgic, but I didn’t want to go back. Looking at my brother, the moment felt fulfilled, and I was thankful just to be there, in the future of my past.

Photo by NASA

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.