The Untold Story of the Doodler Murders

1.

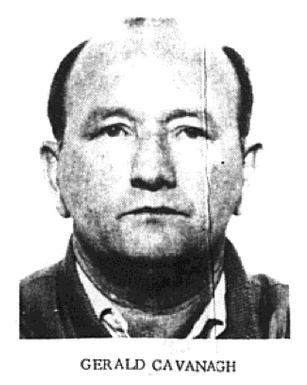

At 1:57 a.m. on January 27, 1974, a corpse was found at the water’s edge on San Francisco’s Ocean Beach. Gerald Earl Cavanaugh, 49, had been stabbed multiple times. His left hand betrayed a defensive wound. His body was, as the coroner’s register put it, “in a supine position” and showed signs of slight rigor mortis. Cavanaugh wore underwear, shoes, socks, pants, a shirt and a jacket. In his pocket was $21.12 and on his wrist a Timex.

As befits a man initially identified as John Doe #7, very little is known about Cavanaugh. He was born in Canada on March 2, 1923, and lived in San Francisco. A photo that ran in the San Francisco Sentinel after his death shows that he was balding. He worked in a mattress factory. He was five-foot-eight and weighed 220 pounds. He was Catholic. “Never married,” wrote the coroner.

Cavanaugh was the first victim in a string of homicides that, to this day, remain unsolved. From January 1974 to September 1975, The Doodler — or, as he was sometimes known, the Black Doodler, on account of his skin color — caught the eye of the Castro’s bar patrons by drawing caricatures and cartoons of them.1 Amused, flattered, perhaps titillated by the attention, man after man would leave the bar with their killer for a more secluded, intimate spot. Once they were alone, the men were stabbed and their bodies left on waterfronts and in parks.

To the extent the case has been written about, the Doodler has been credited with fourteen victims. One encounters this figure in the era’s press accounts and books of recent vintage. But it is far more likely there were, in fact, five or six. (The larger figure may be due to the frequency with which gay men were murdered in those years; it’s possible that several distinct cases were conflated and the Doodler given too much credit.) Five men were contemporaneously identified in the newspapers as Doodler victims, but the count shouldn’t be considered definitive. It’s a fool’s errand to say any single victim is definitely the work of the Doodler, or to rule out the possibility of others. As a veteran detective told me, “Anyone in my position who tells you otherwise, especially when there hasn’t even been an indictment, is either untrustworthy or lying.”

Forty years after the fact, the story of the Doodler killings has not been even cursorily told. Unlike cases with similar body counts — the Zodiac Killer and David Berkowitz, for example — this one was quickly forgotten. It was, perhaps, somewhat a matter of timing. When the killings began, it had been just a year since the American Psychiatric Association Board of Trustees ceased classifying homosexuality as a disorder. Most media outlets, just maybe, did not consider gay men sufficiently sympathetic to rate coverage. And then, four and half years after the killings ended, San Francisco’s own Ken Horne, a ballet school dropout, was reported to the Centers for Disease Control with Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Five murdered men would become, relative to what followed, a statistical blip.

2.

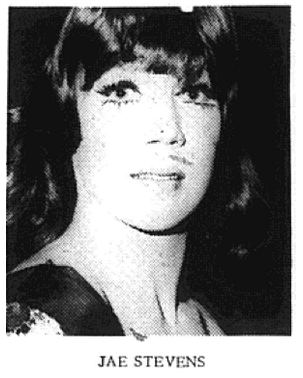

A woman, never identified, found a body at Spreckels Lake in Golden Gate Park on June 25, 1974. Joseph Stevens, nicknamed “Jae,” had been stabbed three times; there was blood in his mouth and nose. He was last seen the previous night, leaving the Cabaret Club on Montgomery Street in the North Beach neighborhood. Police theorized that Stevens himself had driven the murderer to the park.

The 27-year-old was the Doodler’s second victim.

Stevens, born in Texas, was a popular female impersonator and had been named the summer replacement at Finocchio’s. Finocchio’s was an old-time club that had been around since the early thirties. It had once been a hot spot for the military and celebrities, wrote James Smith, but by the seventies “the high tourist attendance and…hands-off rules discouraged the gay crowd and they largely went elsewhere.”2 (It was, clucked the Sentinel, “about as respectable as the First Methodist Church back home.”)3

“When Stevens first appeared on stage eight years ago, he made a sensation in San Francisco as a stunning impersonator,” said the Advocate. “Over the years, however, he had moved away from the role of impersonating beautiful women and concentrated more on gay comedy.”4

The woman who found the body called to Warner Jepson, an avant-garde composer, who in turn called the police. “My God,” said his wife, Andrea, when we spoke recently. “I remember this now. He was in the bushes. Oh my God, I’d totally forgotten. [Mr. Jepson] was walking with the dogs in the park. We had two little kids. He didn’t know him.”5

By 1974, the Castro was for gay men a beautiful refuge from everywhere else. “A clarion call went out in the underground network that San Francisco was the place to be,” said Ron Huberman, the first openly gay investigator in San Francisco’s district attorney’s office, who arrived in 1975. The bar and bathhouse scenes were jumping. Harvey Milk had just opened his camera shop. It was a pre-AIDS wonderland. (While researching this, the astonishing ubiquity of bathhouse ads in the Advocate left me desensitized to microfilmed penises.)

But the San Francisco Police Department would not leave well enough alone. Officers Cornelius Lucy and William Gay, for example, practiced a creative form of entrapment. Officer Gay, as the Advocate put it, would “drive slowly through [Golden Gate Park] in a pickup truck and stop near a strolling male. Then he would stretch out…and show a bulging ‘basket’ in his tight Levis.” Once an advance was made, Officer Gay would make an arrest.

Or worse. Lucy and Gay dragged Lawrence Candler from his car after a minor traffic incident and beat him so badly he suffered brain damage. Neither Lucy nor Gay were charged in the beating because Candler declined to file a formal complaint.6 However, a San Francisco jury eventually awarded Candler $264,500.

3.

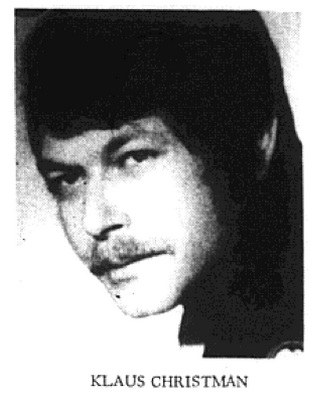

Claus A. Christmann, a 31-year-old German national and employee of Michelin, was the Doodler’s third victim. He was last seen alive at Bojangles.

Christmann was found on July 7, 1974 at the foot of Lincoln Way, by the beach. Tauba Weiss, now 88, was walking her dog, Moondance, and discovered the body. “The dog was running and I followed him,” she told me. “I knew something was wrong. I saw a man laying there and he wasn’t moving. I knew he was dead.” She returned home and called the police.7

Christmann’s throat was slashed in three places and he was stabbed at least fifteen times. “Inspector David Toschi,” reported the Sentinel, “described the murder as one of the most vicious stabbings he has ever seen.”8 (Toschi, a 20-year veteran of the Department, also investigated the Zodiac murders, which are also unsolved. He declined to talk to me.)

At his death, Christmann wore a tan leather jacket, “black side zipper ankle boots with brown cuban-heels [sic], a white Italian (Sela) shirt, orange bikini briefs, one blue moonstone ring and one brown cameo ring along with a gold wedding band.”9 (At the time the Sentinel ran its first story on the murders, Christmann hadn’t been identified. The paper published a photo that appears to have been taken in the morgue.) According to a Homicide Division information bulletin, Christmann was also found with a make-up tube in his pocket, which suggested “homosexual propensities.”10

The police now believed the three killings were connected. Reported the Sentinel:

Police are aware of the similarities between the murder of Mr. Christman [sic] and the stabbing of Gerald Cavanaugh last January. … There also appear to be similarities between these two stabbings and the murder of Jae Stevens, whose body was found stabbed front and back at Stow Lake on June 25th. …

…All apparently involved the victim meeting someone who suggested driving to a remote area as the Beach or Golden Gate Park. All three were viciously stabbed front and back. All three were stripped of identification and property.11

Christmann, who had a wife and two children, had been staying with his friends, Mr. and Mrs. Booker Williams, and had been in the city for three months. His body was returned to Bamberg, Germany for burial. (My attempts to contact his family, and the family of the other victims, were unsuccessful.)

Elliott Blackstone, an SFPD sergeant, had a regular column in the Sentinel called “Off The Beat.” In July, he used the killing of Joseph Stevens to discuss the prevalence of gay murders. “The percentage of the total number of homocides [sic] that have gay overtones is very, very small,” he reassured readers.12

Blackstone’s considerable empathy — one shouldn’t diminish the courage it took to have his byline in the rowdy Sentinel — was not shared by his colleagues, who were still largely Irish and not fond of the gays. (This was true of San Francisco’s Irish at large, too; in the sixties and seventies, they were the source of a real estate boomlet, offloading their Victorian homes in the Castro to eager gays, on the cheap.) The feeling on the street was that police were indifferent to the goings on in the Castro. “If gay men were assaulted for being gay, or robbed, the cops thought gay men had it coming to them, much as they thought women had it coming when sexual assaults happened to them,” said Huberman. “The example that I continually got from cops is, ‘I can’t believe you would just walk into a bar and take somebody home.’”

And there wasn’t even a pretense that gay men would be welcome on the police force. George Eimil, the SFPD’s director of personnel, told the Advocate that, because gays commit felonies, “I guess you could say they are [of] bad moral character. If he is a covert homosexual, there is no question we would not hire him.”13 (He was careful not to enshrine this bigotry in the Department’s policy manual.) Several months later, Captain William O’Connor, the SFPD’s director of public relations, said gays were “emotionally unstable.”14 This pronouncement was retracted after Harvey Milk spoke out against him.15

The homicide rate had begun to tick up as the gay immigration to the city intensified. After a drop at the beginning of the decade — from 112 in 1970 to 97 1971 to 79 and 1972 — the numbers began to rise: 95 in 1974, 129 in 1974 and 131 in 1975.16

Among the victims: George “Marty” Allen, Bette Midler’s hair designer, who was shot near his Castro home on October 19. “I’ll do whatever I want with my own body!” he shouted. Then he died.17

4.

On May 12, 1975 — nearly a year since the murder of Claus Christmann — the Doodler left another corpse; Frederick Elmer Capin, 32, was found by a hiker behind a sand dune between Vicente and Ulloa Streets. Capin — six-feet-tall and a lithe 148 pounds — was wearing a blue corduroy jacket, multi-colored “Picasso” shirt, blue jeans, brown socks, brown shoes and blue shorts. His jacket and shirt were blood-soaked.

The coroner determined that cause of death was “stab wounds of the aorta and heart.” There were marks in the sand leading to Capin, he wrote, “indicating that he had been dragged approximately 20 feet.”

Capin had a sister who lived in Port Angeles, Washington. The local paper, the Port Angeles Daily News, ran an obituary for him; he was a medical corpsman in the Navy and the recipient of a “commendation medal for saving four men under fire in the Vietnam war.” (Capin was easy to identify because, as a registered nurse, his fingerprints had been taken by the state.18) He lived with his grandparents while attending school.19

5.

Harald Gullberg was the Doodler’s last — and, at 66, oldest — victim. John Doe 81 was found on June 4, 1975 on a Lincoln Park golf course by a hiker, ten yards off the trail, slashed across the neck. His pants were unzipped and he wore no undergarments. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that he’d been dead for approximately two weeks; maggots and fly larvae occupied his face.20 (It should be noted that Gullberg was not a healthy man. According to the pathologist’s report, Gullberg suffered from portal cirrhosis; his liver was killing him.)

Gullberg was Swedish and a sailor by profession. He was tattooed on both arms. According to immigration records, between June 1930 and July 1940, he stopped in numerous harbors, including Boston, Puerto Vita, Cuba, Shanghai, Melbourne, San Luis Obispo, Yokohama and Liverpool. He became a naturalized citizen on August 15, 1955.

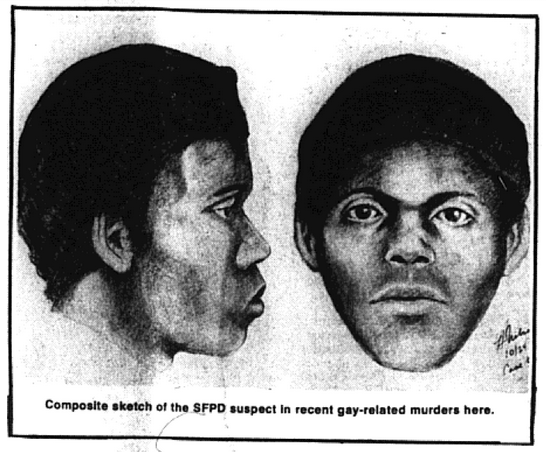

Five months later, the SFPD released a composite drawing of the suspect. He was known, said the police, to “frequent bars and restaurants in the Upper Market and Castro areas.” He was black, between 19 and 22 years old, between 5’10” and 6” tall, slim and frequently wore “a Navy-type watch cap.”21

Police believed the killer had a quiet, serious personality, with an upper middle class education and above average intelligence. Quite possibly he was an art student; he’d informed a witness he was “studying commercial art.” (Alas, one cannot judge the quality of the Doodler’s work — his sketches were never shown in the press.) The police also believed the suspect had a history of, as UPI put it, “mental difficulties involving sex.”22 Indeed, reported one paper, he had “sexual identification problems” and was undergoing psychiatric care on “an out-patient basis.”23 According to the Chronicle, he told each victim, “All you guys are alike,” by which he meant gay.24

Witnesses were reluctant to cooperate with the police. “My feeling is they don’t want to be exposed as homosexuals,” Inspector Rotea Gilford would say, a few years later.25

“I’d sure like to talk with anybody who’s been attacked,” Inspector Frank McCoy told the Sentinel, which had been flooded with tips. “And I’d really like to emphasize that the information we are receiving will be kept confidential.”26

In the absence of an arrest, there were rumors. The late Charles Lee Morris, owner and publisher of the Sentinel, told the Chronicle about a Los Angeles man who encountered the Doodler. He was about to go to bed with a young black man resembling the composite sketch, but changed his mind when a knife fell out of the man’s coat.27

Numerous press accounts mention three surviving witnesses. One was a European diplomat assigned to the States who, in May 1975, met the suspect in an Upper Market restaurant “where he was having a midnight snack.” Reported the Chronicle, he “asked if [the diplomat] had any cocaine.” They went back to the diplomat’s apartment, where the suspect stabbed him six times. For his part, the diplomat denied he’d had “sexual relations” with the suspect. (In 2011, I submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the State Department for names of European diplomats based in San Francisco; nothing came of it.) Another surviving witness was an entertainer of some kind who, according to police, was “nationally known.” The third — described by the Sentinel as “a well known San Francisco figure” — left the city and reportedly wouldn’t answer letters or phone calls. (The San Francisco Police Department declined to comment for this story. “We don’t discuss open investigations,” Sergeant Monica MacDonald told me.)

The identity of the “nationally known” figure is one of the great secondary mysteries of the case. To my surprise, his name never leaked into the gay press. I asked Randall Alfred, the Sentinel’s news editor in 1975, who the entertainer might have been. “Was it Johnnie Ray? Was it Rock Hudson? Richard Chamberlain?” he said. “It was a time of very cheap airfare from L.A. to San Francisco.”

Of the three, only Chamberlin is still alive. “No comment,” said his manager.

More than a year after the Doodler killings began, little progress had been made on the case. It would be pleasant to think of the Doodler murders’ unsolved status as an aberration, but it was not. When, on May 2, Nick “Granny Goose” Bauman was found dead in a South of Market basement — his skull fractured — his was the 21st murder, and unsolved murder, of San Francisco’s gay men during the last year and a half. Gilford, who caught the case, said the 29-year-old’s scrotum looked “like someone had stomped them into nothing.”28

The San Francisco Chronicle more or less ignored the Doodler killings until they were over. (A note: the Advocate and, in particular, the Sentinel did extraordinary work covering this story. My footnotes are an attempt to preserve their efforts.) In January 1976, Maitland Zane, whose obituary praised his “writing about those on life’s margins,” wrote a page two story about the spate of homicides with the misleading headline “The Gay Killers.”29 The city, he wrote, had become “nightmarishly dangerous for gay men,” of whom seventeen had been murdered in the last year:

Six of the killings have been linked to the sadomasochist leather bars and bath houses in the Folsom street district.

Teams of Homicide detectives were also pressing the hunt yesterday for the Tenderloin slasher who mutilates his “drag queen” victims, and for a smiling black cartoonist believed responsible for stabbing six men he picked up in Castro Village gay bars.

Chronicle readers responded in various ways. They complained about the “wealth of sordid and unnecessary details”; they groused that the killings might reflect badly on the leather bars (“Surely maniacs are present in all walks of life.”); and they worried the coverage would only make things worse (“Publicizing areas where gay men hang out will most probably increase the numbers of attacks and murders.”).30

After the Chronicle’s story ran, the SFPD, besieged with tips, questioned a number of suspects. One man, who resembled the composite sketch, was taken into custody after he entered a Tenderloin bar and offered to draw the patrons. Along with a book of sketches, he’d been carrying a butcher knife. (He was booked for carrying a concealed weapon and, after he attacked homicide inspectors during an interrogation, charged with aggravated assault.)

The man, said Gilford, “is one of the many suspects being checked.”31

In fact, there were dozens of suspects, and at least one of them looked good for the murders. In July 1977, Gilford said a suspect had for the last year been questioned and had “talked freely” with police but declined to confess to the killings. The police, reported UPI, “are ‘fairly certain’ that ‘The Doodler’ is involved in the slayings, but court testimony of the survivors would be needed to identify him.”32

A week later, the Sentinel reported that the department knew, thanks to an anonymous tip, the license plate number of the suspect’s car and had even “spoke[n] to the psychiatrist who treated the Doodler.” (The Sentinel also gleefully revealed that, according to the SFPD, the killer was heterosexual. Headline: “Straight sought in mass gay slayings.”)

“The psychiatrist told investigators that [the suspect] admitted during one session that he had committed the brutal slayings.”33

Three and half years after the killings began, Harvey Milk — who, four months later, would be elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors with 30% of the vote — was asked about the case and, in particular, the uncooperative surviving witnesses. “I can understand their position. I respect the pressure society has put on them,” he said. “They have to stay in the closet.”34

After that, mentions of the Doodler murders nearly vanished, even among the gay publications. A culturally significant exception: In 1978’s Tales of the City, Armistead Maupin writes of “the Doodler, a sinister black man who sat at the bar and sketched your face . . . before taking you home to murder you.” But otherwise, it’s been almost entirely lost to history. (A recent memoir, by a man who purports to be the son of the Zodiac Killer, mentions the Doodler, and an e-book treatment of the case — comprising little more than a Wikipedia entry — was published last year.)

Several years ago, I wrote to the University of Arizona’s Susan Stryker; her excellent Gay by the Bay: A History of Queer Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area contains a line about the case. “The only people I found who remembered the killings were trans women who lived in the Tenderloin at the time,” she replied. “It is a very poorly-remembered episode in SF LGBT history.”

Forty years later, finding anyone who knew the men is awfully difficult. In fact, I had no luck. (In the coroner’s reports I was given, the names and contact information of the victims’ friends and family had been redacted.) It was a shot in the dark, but I read off the names to Jerry Pritikin, 77, who moved to the Castro in 1964 and remained in San Francisco for two decades. “One thing about being young and gay,” he said, “you know a lot of people by their first name, but not necessarily their last name.”

The August 16, 1978 edition of the Crusader, a long-gone gay paper, may have been the last periodical to cover the Doodler.35 The story is headlined “POLICE ARE ‘NOWHERE’ ON DOODLER KILLINGS.” The writer raged against the inaction and ineffectiveness of the San Francisco Police Department, and blistered it for its failure to charge anyone. He foresaw more death:

Thus, the killer continues to walk the streets, drink in his favorite Castro bars and go to his favorite gay baths……maybe planning on killing even more!36

1. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Doodler Suspects,” January 29, 1976.

2. San Francisco’s Lost Landmarks, James R. Smith.

3. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Finnocchio’s: about as respectable as the First Methodist Church back home,” September 21, 1974.

4. The Advocate, “Police suspect Gay–haters in series of stab murder,” August 14, 1974.

5. Interview, September 15, 2014.

6. The Advocate, “Man beaten by homophobic police gets court settlement,” December 18, 1974.

7. Interview, September 15, 2014.

8. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Reader identifies last of three victims,” August 9, 1974.

9. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Police investigating link in 3 recent stabbings,” July 26, 1974.

10. The Advocate, “Police suspect Gay–haters in series of stab murder,” August 14, 1974.

11. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Reader identifies last of three victims,” August 9, 1974.

12. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Off The Beat,” July 18, 1974.

13. The Advocate, “Views from enforcement officials,” January 29, 1975.

14. The San Francisco Sentinel, “SFPD pronounces us ‘unstable,’” October 9, 1975.

15. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Police retract anti-gay quote,” October 23, 1975.

16. “Homicide in San Francisco, 1849–2003,” Kevin Mullen

17. The Advocate, “S.F murder could be the work of homophobes,” November 20, 1974.

18. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Murder unsolved,” May 22, 1975.

19. The Port Angeles Daily News, “Deaths and services,” August 15, 1975.

20. Coroner’s Register

21. The San Francisco Sentinel, “SFPD Describes Suspect In Murder Cases,” November 5, 1975.

22. United Press International, “3 Attack Victims Won’t Testify in Unsolved Deaths,” July 9, 1977.

23. The Crusader, “Police Are Nowhere On “Doodler” Killings,” August 16, 1978.

24. The San Francisco Chronicle, “The Gay Killers,” January 20, 1976.

25. The Associated Press, “Murder suspect free because gays silent,” July 8, 1977.

26. The San Francisco Sentinel, “SFPD Describes Suspect In Murder Cases,” November 5, 1975.

27. The San Francisco Chronicle, “The Gay Killers,” January 20, 1976.

28. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Violence Rises,” September 6, 1976.

29. the San Francisco Chronicle, “The Gay Killers,” January 20, 1976.

30. The San Francisco Chronicle, “Letters To The Editor,” January 29, 1976.

31. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Doodler Suspects,” January 29, 1976.

32. United Press International, “3 Attack Victims Won’t Testify in Unsolved Deaths,” July 9, 1977.

33. The San Francisco Sentinel, “Straight sought in mass gay slaying,” July 14, 1977.

34. The Associated Press, “Murder suspect free because gays silent,” July 8, 1977.

35. The Weekly World News ran a Doodler item in 1999, which I only mention in the interest of thoroughness.

36. The Crusader, “Police Are Nowhere On “Doodler” Killings,” August 16, 1978.