Other People's Christmas Photos

by Andrea Volpe

If you search the terms “Christmas” and “snapshot” on eBay, you will get a list of more than one thousand photographs. Think Diane Arbus with an Instamatic. In one shot, two wide-eyed girls in matching striped pajamas stand beside their matching dolls. In another, the girls, still in pajamas, sit before a decorated tree with their brother, who is wearing his Boy Scout uniform. Then there are the sketchy Santas. So many tinseled trees I lost count.

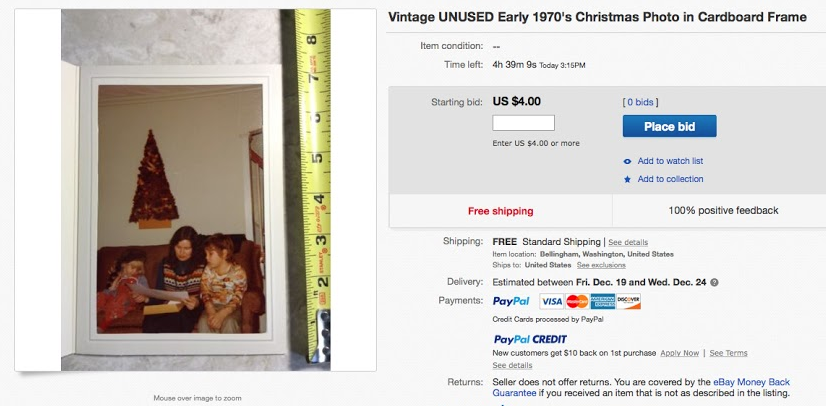

These images were never meant for sale, or to be seen by strangers, but here we are. Now, thanks to the widespread assumption that anything and everything can be sold on the internet, images of someone else’s Christmas are for sale to the highest bidder. (That said, for the most part, no one’s buying; a great number of surveyed images have exactly zero bidders.) A market, by definition, is where people assemble to sell and buy commodities. But that doesn’t mean they agree about the nature of the thing being sold or bought.

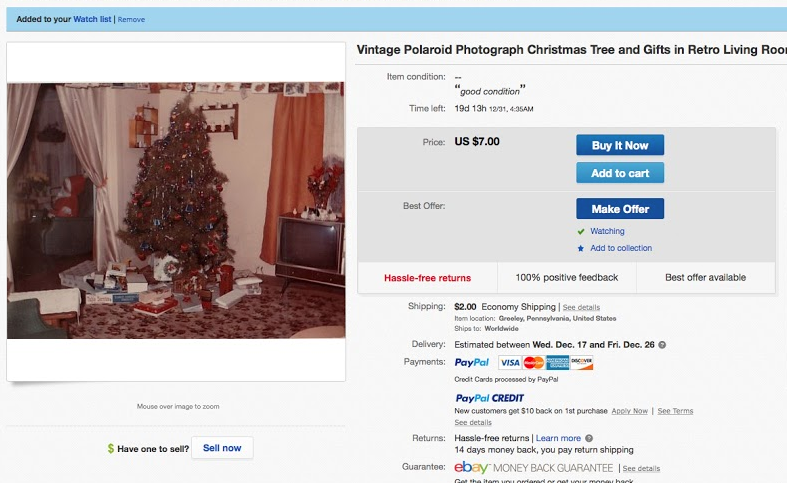

The Christmas tree is the money shot of the genre. Christmas trees with tinsel. Christmas trees with children. With presents ready to be opened. After the presents are opened. (As in early battlefield photography, it’s hard to get an action shot.) A surprising number of trees beside a TV set. A television set! How quaint. But not as many cats as you might expect, and not that many crèches or wise men, either.

Chalk it up to inexorable progress that digital has made markets for things that hardly had markets before, scaling up the garage sale into something enormous and rational. This is fine when it comes to utilitarian objects like, say, Pyrex. Everyone needs mixing bowls; if they are from 1978, fine. But we are talking about a market for snapshots that were supposed to be so personal and precious that there shouldn’t be a market for them. What is being sold and being bought here, exactly?

On the sellers’ side, the clues are in the captions. Take for example “Old Antique Vintage Photograph Dad With Children Christmas Tree Train Set Gifts,” Or even better, “AWKWARD FAMILY CHRISTMAS PHOTO TREE TINSEL FASHION VINTAGE SNAPSHOT PHOTO.” All caps says it all. To paraphrase Tolstoy, what family at Christmas isn’t awkward?

These photographs need their captions, because now that they are detached from the context in which they were made, they are virtually meaningless. The code words “retro” or “antique” or “vintage,” appear with remarkable regularity, as in “Old Vintage Photograph Gorgeous Christmas Tree All Decorated Retro Xmas.” Most often it’s the photographs themselves that are described as “vintage,” and it’s the objects pictured in them, particularly TV sets, that are what’s “retro.”

But retro is the wrong word. These photographs aren’t imitative of the recent past, they are the recent past. Nor are they antique — collectible or valuable because of their age or high quality. The consistency of the captions isn’t accidental. The sellers know full well there’s something pathetic about these photos — a disassociated nostalgia that has to be overcome in order to make a sale, and yet which ultimately stands as the element of the photograph with the most value. The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction was supposed to not just be economically cheaper, but also emotionally and aesthetically cheapened. Now, in the age of digital reproduction, what was mechanical, multiple, and devalued has become almost unique and valuable.

That doesn’t mean I’m entirely comfortable buying. Scrolling through these pages is like walking through the neighborhood and looking through someone’s living room window for too long. You’re fascinated but you know you’re prying. It’s interesting looking at pictures of other people’s families, until it’s not, and then its sad and a little icky, thinking about what turn of fate separated family photographs from their families. There’s also a strange flicker of recognition that comes from seeing screen after screen of oddly familiar scenes, as if we’re supposed to recognize the people in the photos after all. Is that Aunt Rosalie? Cousin Charlie? Could be. Not sure. The motivation to buy is still complicated: Maybe you want to rescue the people in the photo and give them a home. Or you think the image is really, really cool, or really, really sad, or cool because it is sad.

Even as I was compelled to look at each and every one of these 1,123 photographs, I found myself performing a sort of visual triage as I scrolled through, trying to separate the good ones from the bad ones. I was judging them based on their proximity to or distance from an aesthetic, even as I knew, intellectually, that none of them were any good. Isn’t a discarded snapshot, by definition, valueless?

Maybe not. The only way I could contemplate buying any of them was by arranging them into a typology, where the sum is greater than any single part. Take the Christmas tree. Most of the trees in these pictures make the Grinch’s tree look lush. Individually, they are depressing. But together, in a series, they are arch and ironic. That’s when I started buying Christmas tree snapshots. No people. Just the trees.

It was oddly comforting. If the photos are of a type, then maybe we can find ourselves in them, burnishing our own singular banal experiences — memories of Christmases past — and making them into something more than they were.

I valued the photographs for how they looked, not the specificity of the experience alluded to by the literal content of the image. I could separate signified from signifier. I wanted the photograph because I valued the style in which it was rendered, not because I wanted the tree itself.

Essentially there are two ways to make sense of experiences worth photographing. The first is to think of yourself and what’s happening to you as unique and special, so it’s worth capturing on film (or with pixels). This is the logic of the snapshot, and this is why our phones are now cameras. We are all so very, very special these days that we can, and do, take nearly infinite photographs.

The other explanation is that we are not that special at all, we are merely heeding a cultural formula, one that is bigger than we are, that we learn to see through, and that we imprint on our individual experiences. This is also the logic of the snapshot. We know by cue when something is worth photographing; when we drive by a spot in the road labeled “scenic overlook,” or after we put up the Christmas tree.

Let’s go back to Diane Arbus for a minute — because her deadpan style owes so much to snapshots and because in 1963 she took a picture of a Christmas tree in a Levittown living room. Arbus, who worked in black and white, and William Eggleston, who worked in color, elevated the snapshot into art by distilling its formulaic aesthetic and expressing it as something more. Now, as an eBay shopper, I could see a little like Arbus and Eggleston had, turning the snapshot back on itself. I found images that were sort of like an Arbus and a little bit like William Eggleston’s world: brash, and too-close-up, and saturated with color. I’m still kicking myself for missing out on the best Arbus-like photograph, but I landed a nice Eggleston look-alike.

There was something a little off-kilter about this. The snapshot starts its life saturated with context. Specificity matters more than anything else, so much so that the style of the photograph is virtually unconscious. But give enough people a chance to point a camera at a Christmas tree, and generic conventions emerge. Form follows function: to remember, to commemorate, to document. When that distinct style is appropriated, as it was by Arbus and Eggleston, we become more aware that style in a photograph is something to be deployed, even as their work depended on and even reinforced the boundary between art and kitsch.

The thing that we are most afraid of about our photographs is that they won’t be recognizable, that we will forget the names of the people in the picture, that they will lose context, and lose meaning. We fear that this will make them lose their value. But on eBay, lack of meaning is their most desired quality.