A Rapper for Zion

by Alex Cocotas

On the evening of July 12th, a few hundred activists gathered in front of the national theater in Tel Aviv’s Habima Square to protest against the ongoing military operation in Gaza. They carried signs that said things like, “End the occupation,” “Stop the slaughter in Gaza,” “IDF [Israeli Defense Forces]: the most ethical terror organization in the world,” and “We do not want a government of inciters.” Shortly after the protest started, a few counter-demonstrators arrived to shout down the protesters. Over the course of an hour, their number rose. Most were young men with close-cropped hair or shaved heads; some appeared not yet out of high school. Many carried Israeli flags, and a seemingly inexhaustible list of insults. They sang the national anthem, called protestors “terrorists” and “traitors,” and chanted, “The nation demands that leftists be expelled.” A few wore t-shirts with a neo-Nazi symbol.

Habima Square lies at the end of Tel Aviv’s most posh street, Rothschild Boulevard, a picturesque, tree-lined route dotted with crumbling Bauhaus buildings. At most protests, demonstrators and counter-demonstrators face off where it turns into a T-shaped intersection in front of the square — one group on Rothschild, the other in the plaza. On this night, however, the police did not enforce the prevailing division; both sides were inside the square, with only a single, permeable row of officers between them. As tensions mounted, police did little to defuse the situation, even as some counter-demonstrators began trying to physically assault the anti-war activists.

One of the counter-demonstrators was a large man covered in tattoos named Yoav Eliassi. He stood a few feet behind the police line, bobbing his head under a baseball hat and intermittently checking his phone. Earlier that day, Eliassi had written on his Facebook, “Today at 8:00 in Habima Square, we are representing the IDF that is protecting us, across from the ungrateful and disrespectful left that in the time of war dares to protest for our enemies and against the IDF, so leave Facebook for the moment and come to show that we are not suckers.” In the comments, people responded to the call and told him they were on their way. Later, he posted a video with the comment, “Currently waging war in Habima Square for the dignity of the country and the IDF. We are 80 across from 500.”

That same day, Hamas had publicly promised an unprecedented bombardment of Tel Aviv at 9 p.m. “As nine o’clock approached we began thinking about what would happen if [they] realized their warning,” wrote the Israeli journalist Haggai Matar, who participated in the protest. A little more than an hour after the protest’s start, two sets of sirens rang out, swathing the city in their stifling moans, driving most of the police toward bomb shelters. Interceptions from the Iron Dome missile defense system boomed above the city. One interception, directly over the square, lit the night sky with an orange burst, causing everyone to pause long enough to gaze at the sky until the distorted ghost of ash and smoke vanished.

After the sirens ended, it was agreed that the peace activists would leave under a protective cordon from the cops, but a group of counter-demonstrators snuck around the police line and attacked the fleeing protestors. Before the police could reestablish order, numerous activists were assaulted; one had a chair smashed over his head, and others were chased into cafes to seek refuge.

Eliassi took to his Facebook once again: “Thank you to all who came. We started with three across from 800 and we finished with 350 across from zero of theirs. It was crazy to do all this with the sirens in the background and explosions in the sky, but we did not move and stood our ground until the end. The police representative (who, by the way, treated us great and we saw the pride on the faces of the special forces and the restraint toward our side) took me aside and wanted to see these lions of the Shadow –and thus he gave a name to the group I’m organizing, which is essentially all of you…Together we are a force against the real enemies that walk among us, the radical left, and thank you to my friends that are apparently called the lions, and thank you very much to the IDF all this is for you!!”

Eliassi is better known as The Shadow, a once-ascendant Zionist rapper who had largely faded from public consciousness over the past decade, and his second act as a right-wing street organizer and demagogue was just beginning.

Hip hop first came to Israel in the nineties. In contrast to its American progenitor, Israeli hip hop was notable for primarily vocalizing the views of mainstream culture, and it eventually coalesced around the thematic pillars of Zionism and national identity. There was a subtle undercurrent to this development: By focusing on Zionism and Israeli identity, which historically draw their strength from existential threats amid a hostile world, Israeli rappers could recast themselves as marginal figures and assume the outsider status that hip hop’s origins seemed to demand. They, in effect, reconfigured the mainstream under the guise of a marginal voice.

The most vocal proponent of this style of “Zionist rap”was Kobe Shimoni, known as Subliminal, who would go on to become Israel’s most famous and influential rapper. It was Shimoni who convinced Eliassi, a long-time friend, to pursue a music career after failing to land his dream job as a cop; Shimoni became the lead man in an emerging tandem act with Eliassi, falling somewhere between hype man, fearsome presence, and semi-permanent guest star. Their music was tinged with nationalist sentiment from the start — partly a reaction to the perceived paucity of national pride among popular musicians, but it was also heavily indebted to the style, wordplay, bravado, and violent imagery of American gangster rap.

They first gained wider recognition with the release of Shimoni’s 2000 album, “The Light from Zion,” which featured Eliassi on several songs, most prominently the hit “Living From Day to Day.” It caused a minor uproar in the press — one headline read: “Ku Klux Klan: I’m Terrified of Subliminal’s Racist Hate Music” — although most the lyrics are fairly mild, especially compared to some contemporary rhetoric. More important, however, was the album’s timing: The collapse of much-hyped peace talks that same year was swiftly succeeded by the Second Intifada, largely synonymous with the subsequent wave of suicide bombings in Israeli memory. In an atmosphere increasingly permeated by fear and distrust, Shimoni and Eliassi’s unapologetic nationalism struck a chord with listeners.

As the security situation deteriorated, Shimoni and Eliassi became increasingly devoted to creating their aggressive brand of Zionist rap. “Making music is fine,” Shimoni said at the time, “But I always said that I use music as a means. My goal is to relay a message.” Their next album, the 2002 combined effort, “The Light and the Shadow,” made them household names, selling over a hundred thousand albums in a country of eight million people. On one song, “Biladi,” the chorus, sung in Arabic, is “This is my land / This is my country,” a clearly formulated middle finger to Palestinians. When asked why it was in Arabic, Shimoni answered, “Because the people who are supposed to understand it understand Arabic,” although Subliminal less-than-convincingly asserted that he is a “Jew that respects Islam.”

The album’s success changed Eliassi’s life. As a child, his family’s finances were chronically unstable. His dad frequently turned to scams to make money — Eliassi once woke to find a cop searching a closet for his fugitive father. After the start of Eliassi’s mandatory three-year military service, his father, who had just survived a murder attempt, was convicted of fraud and the family sank deeply into poverty; Eliassi resorted to stealing from the army to help keep food on the table. Now, for the first time in his life, he had money. He lived in penthouse apartments, spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on cars, drank heavily and harbored a burgeoning sex addiction. He later told NRG, “If I did not [have sex] with four women a night in the bathroom of the club, I could not return home.”

Shimoni and Eliassi maintained a relentless touring schedule at the height of their popularity — roughly the first half of the decade — criss-crossing the country to play smaller communities otherwise ignored by the cultural establishment, furnishing their act with something of a populist feel and making them an instantly recognizable presence to much of the population. For many, their music embodied the anger, anxiety, and latent isolation that pervaded as violence enveloped the country amid an ever-louder echo of criticism from abroad.

But interest in aggressive, hyper-nationalist music began to wane as the security situation stabilized and the Second Intifada faded. Eliassi’s long-awaited solo album, “Don’t Give A Fuck,” wasn’t released until 2008 and relatively few fucks were given by the listening public. Declining sales and extravagant spending habits led to financial problems; in March of 2011, he was declared bankrupt. As his output declined, Eliassi became a source of gossip fodder, known as much for trying to smuggle his Chihuahua into restaurants as for his music. Whatever his frequent complaints about the media, continued press coverage seemed a matter of some existential bearing, “The moment that they stop writing about me in the gossip section, I simply will not be there anymore. As long as they are writing about me, it means that everything is ok for better or worse….If [someone] is not in the gossip section, this means that he is not worthy of gossip and this means that this person does not exist.”

After a protracted spell of being below radar, a video of Eliassi arguing carnivore rights with vegan activist Tal Gilboa — who, incidentally, just won Israel’s most recent season of Big Brother — went viral on Facebook earlier this year. The experience was instructive. In a recent interview [Hebrew], Eliassi said it was the first time he realized the power of Facebook. In June, after three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped, and subsequently found murdered, his statuses pushed for a greater military response and he took part in the government-sponsored #bringbackourboys campaign — adding his own tagline: or we’re coming for yours. He described the discovery of their bodies as very difficult for him, and again called for greater retribution on Facebook. Most memorably, he posted a picture of himself, since removed, holding a photoshopped pair of testicles while affecting a solemn mien, which said, in red, “revenge,” and in white, “BB [Netanyahu’s nickname]. I think you forgot these!!”

After the July 12th protest, Eliassi’s name dashed across the country’s major media hubs for the first time in years, quickly becoming the face of some vaguely defined phenomenon, characterized by an unprecedented cascade of pressure on the conflict’s few public dissenters. Three days after the protest, he rolled out a Facebook page for his new organization, “The Shadow’s Lions.” The lion, he later clarified, is a symbol of Israeli unity, his organizational aspiration. (Though in one post, Eliassi called it a “Zionist army.”) The page had more than thirteen thousand followers until it recently disappeared without warning. Eliassi’s personal fan page, which seems to have been dormant for a year (and sparsely used before that), was re-activated and became his central communication hub, gathering more than forty-nine thousand followers over the past four months. It quickly became something of a one-man media center, a place where Eliassi could muse about war developments, spew vitriol at rivals, inflame followers with perceived injustices, or wax maudlin about his fate as the conveyer of these truths. A cursory scan of his page indicates the majority of his fans seem to be young men (and Facebook confirms that between eighteen and twenty-four years old is the most popular age group of his followers). (Eliassi did not accede to an interview request, but said I could send him a list of questions, which he has so far ignored).

Tens of thousands of followers might seem insignificant, but relative scales matter. The total population of Israel is over eight million. Over 5.2 million are non-ultra-orthodox Jews, who form the bulk of Hebrew-speaking Facebook. To draw an unfair but nonetheless instructive comparison, a similar proportion of likes in the United States would be over two million followers. Eliassi’s following, additionally, is comparable to influential political figures: Zehava Galon, head of the largest left-wing party, Meretz, has sixty-four thousand followers; Isaac Herzog, head of the center-left Labor party, has forty-seven thousand.

Eliassi has become a target of criticism in the months that followed, mostly from the left. Internet memes dressed him up as a Nazi. The Minister of Education, from the center-right Yesh Atid party, accused him of “polluting the souls of Israeli children,” tapping a collective anxiety about the growth of extremism among Israeli youth — a fear compounded after virulently anti-Arab protests in Jerusalem last summer were rife with visibly underage participants. Eliassi’s oft-posted portraits with smiling soldiers certainly did not alleviate anxieties, either. However, he strenuously denied any involvement in the violence, insisting it took place after he left the protest and was no longer involved.

Although Eliassi has faced some hostile questioning in the press, the public has been sympathetic on his central issue: The attitude towards anti-war protestors is almost uniformly negative. A common sentiment, which I heard personally on several occasions, and versions of which could be found in the media, from passing hecklers at protests, to in the infamously toxic “talkbacks” under news articles, was: “Yeah, I know, democracy, but… not while there is a war.” While some mainstream Israelis indubitably found Eliassi to be ridiculous, the logic of the atmosphere dictated that he had to be accommodated, lest questions of one’s own sympathies come under suspicion; supporting the troops, even as vague declamation, was an unassailable position, not so easily excised from the public discourse. This, perversely, probably served to increase his audience: The number of counter-demonstrators at anti-war protests swelled in the weeks the July 12th demonstration. Eliassi said at the time, “I feel that I became a leader without intending to. Decision makers from the right turn to me in order to receive suggestions from me. I entered a restaurant yesterday and everyone was standing on their feet and chanting for me.” More recently, the country’s largest newspaper ran a long, largely sympathetic interview with Eliassi in their weekend edition, running to almost five thousand words.

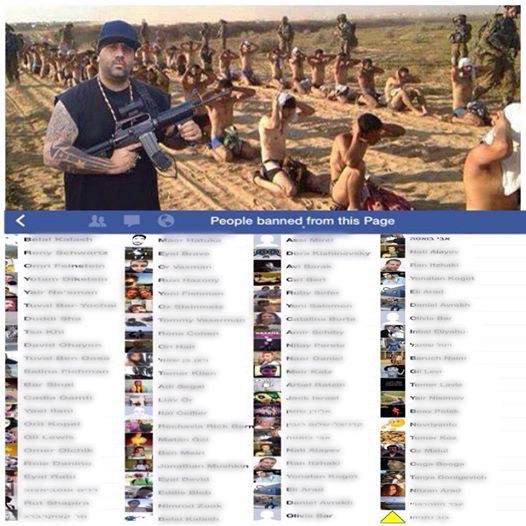

Eliassi’s re-found prominence following the protests and media coverage has not translated into a coherent strategy for his organization, which appears haphazardly strung together without little sense of direction; it is unclear what Eliassi ultimately hopes to achieve. Eliassi or his group have also posted pictures of people, perceived political enemies, on their Facebook pages along with their name and offending quote or action. Sometimes the target was prominent, such as a video of them yelling at left-wing columnist Gideon Levy (eleven thousand likes), but more often it was a seemingly random person who’s Facebook post had somehow found its way into their hands. Palestinian citizens of Israel seemed to be singled out for special treatment. Some of these people reportedly lost their jobs.

Many critics point to Eliassi’s re-emergence as a shameless attempt to restart his music career. Eliassi waves off these accusations as if they are self-evidently ridiculous. There is some truth to his contention: Although he has released a few songs recently, even he acknowledges that there is not much appetite for hip hop in Israel these days. However, this takes a narrow definition of what constitutes his career. If you take the “The Shadow” brand — as someone to pay attention to, listen to, or write about — as a natural extension of his career, it is inextricably weaved into the texture of his activities, which primarily seem to be announcing and organizing counter-demonstrations to planned pro-peace, anti-war, or anti-occupation protests; collecting and distributing consumer goods to soldiers stationed near Gaza during the war; and posting many, many pictures of lions and the Star of David photoshopped together.

Eliassi is ultimately only a symptom of the current atmosphere in Israel: Without a fundamental change in its prevailing political culture, he will be neither the last nor least benign of these characters to emerge — but recent developments do not portend a foundation for positive change. The resolution of the Gaza conflict in late August was inconclusive and did nothing to substantively address its underlying causes; the expectation of renewed hostilities is widespread. Near-daily protests and violence in Jerusalem have shattered the illusion of a tentative calm and some suggest it may auger a new, semi-permanent instability. The specter of international isolation, more than ever, haunts the political horizon. Part of the problem is institutional: despite weeks of protests marred by right-wing violence, more peace activists were arrested on August 2nd for trying to stage a small pro-peace demonstration than from any single incident of right-wing violence. But it also represents a societal drift, driven by a traumatic legacy of violence, economic precarity, an ideologically charged school system, and reckless political opportunism, padded out by a largely acquiescent media.

The effect of Eliassi’s campaign is to further narrow the already tapered space for public debate in Israel. Eliassi’s aspiration of national unity may echo his earlier calls to increase national pride, but it is less about nourishing your spirit at the collective well than erecting a framework for excluding voices outside of an inexact consensus. While he says everyone is entitled to their own opinion, if you care about human rights or question the army’s infallibility, you are classified as one of the “real enemies that walks among us,” compared to terrorists, and subsequently made eligible for public harassment. While not officially-sanctioned, it helps create informal barriers to speech that are intolerable for the average citizen, enforced by an implicit threat of violence. Nonetheless, shades of Eliassi’s rhetoric can be found among mainstream pundits and politicians: musings that those not “loyal” to the country should be stripped of their citizenship foreshadowed a similar move recently suggested by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

On August 9th, a coalition of left-wing groups planned a large pro-peace rally in Tel Aviv. The police pulled the rally’s permit a few hours before its start, but a few hundred demonstrators turned out anyways. They were met by a group of counter-demonstrators, including Eliassi and his lions. One of the counter-demonstrators held up a sign that read, in Hebrew, “One people, one country, one leader,”an almost exact translation of the Nazi’s famous formulation, “Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer.”A few days later Eliassi took to Facebook to clear up the matter. “Extremist leftists”had “infiltrated”the protest and distributed the signs to his “innocent”people who did not understand the “blatant and extreme criminal incitement of the radical left.”About a month before, Eliassi released his first song in years. It was called “One Blood.”The chorus was “One nation / One blood / Come against us? / No one / One God / One heart / You won’t walk alone with the number one army.”

Photos via Facebook