The Water in Majorca Don't Taste Like What It Oughta

by Josephine Livingstone

In this 1985 ad for Heineken, a girl, played by the unforgettably named Sylvestra le Touzel, is trying to learn something. She’s sitting in a teacher’s office at the School of Street Credibility, playing the part of a Sloane Ranger unable to enunciate properly. Again and again, her teacher shakes his head in frustration: She’s mispronouncing the Spanish island Majorca. It’s “ma-jaw-kah,” not “ma-yaw-ker”! She just doesn’t get it, the dense mare. Only after cracking a tinnie of Heineken does Sylvestra finally open her mouth to produce the musical strains of pure cockney. Success! Jubilation rings through the office as her riches-to-rags transformation is complete. “Heineken refreshes the parts wot other beers cannot reach.”

Why is this funny? Obviously, le Touzel is a cracking actress. But this is also a straightforward riff on a scene in My Fair Lady, George Cukor’s movie of the musical of the play by George Bernard Shaw. As you will recall, My Fair Lady is the original “betting on a makeover” film: Professor Henry Higgins wagers that he can turn a dirtbag flower girl into a real lady, only realizing that he loves her after she nearly gets stolen by cute aristocrat Freddy Eynsford-Hill (played by the babely Jeremy Brett).

Heineken (or rather, the ad agency Lowe Howard-Spink) is skewering the scene in which the poor tortured Eliza Doolittle tries and fails, over and over again, to produce the right vowels in the phrase “The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain.” In the movie, Henry Higgins (Rex Harrison) bullies and cajoles and dominates Eliza (Audrey Hepburn) until, finally broken in, she gets it:

As in the Heineken ad, Eliza Doolittle suddenly, magically arrives at phonetic perfection. This isn’t the slow grind of elocution training. It strikes her instantly, after Higgins pummels her with the idea of English:

“I know your head aches. I know you’re tired. I know your nerves are as raw as meat in a butcher’s window. But think what you’re trying to accomplish — just think what you’re dealing with. The majesty and grandeur of the English language; it’s the greatest possession we have. The noblest thoughts that ever flowed through the hearts of men are contained in its extraordinary, imaginative and musical mixtures of sounds. And that’s what you’ve set yourself out to conquer, Eliza. And conquer it you will.”

In reality, this kind of change in enunciation would happen slowly, not quickly. As Peter Ladefoged describes in his book Vowels and Consonants (2001), phonetics was borne of Victorian science, making it fitting content for a musical rom-com set somewhere between 1901 and 1910. The technique of thinking of vowels in terms of “tongue height, tongue backness, and lip opening” was developed by Alexander Melville Bell, the father of the inventor of the telephone: “Both father and son were excellent phoneticians, and used to give public demonstrations of their skill,” write Ladefoged. The duo regularly astounded audiences: One would take down a volunteer’s speech in their phonetic transcription method, “Visible Speech,” then the other would read it back to the volunteer, perfectly mimicking his or her accent, without ever having heard the speaker. I only mention it because this is a crucial element My Fair Lady. Peter Ladefoged the phonetician, again, talking about his work on the film:

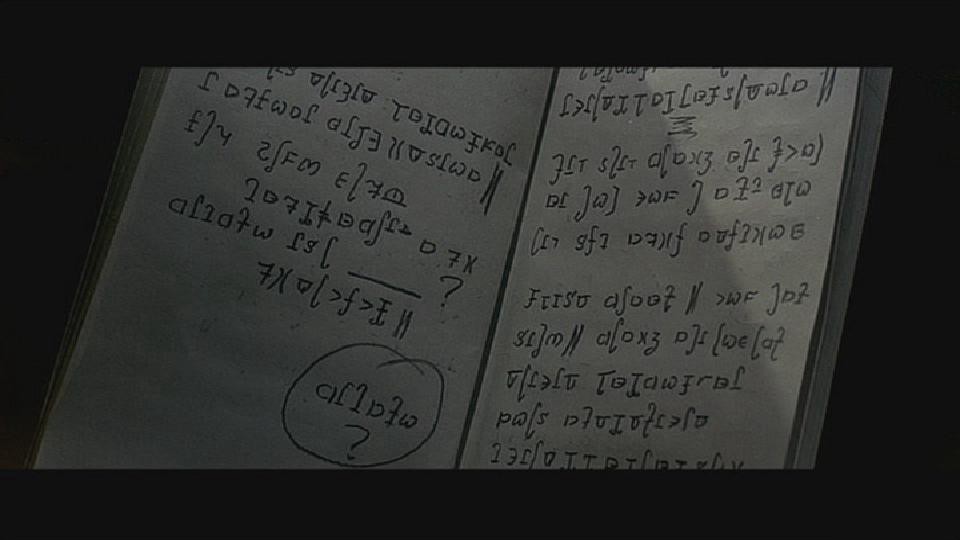

You can see some examples of Visible Speech in the film My Fair Lady. I was a technical consultant on the film, and wrote the transcriptions that can be seen in Professor Higgins’s notebook. You can also see a chart of the vowels written in Visible Speech, which Professor Higgins uses when demonstrating the different vowels to Colonel Pickering. It is actually my voice that you hear saying the vowels, not Rex Harrison’s.

Here is that notebook shot of Visible Speech:

Alexander Melville Bell designed this system in order to help deaf people learn to speak intelligibly, not to teach poor girls how to sound like rich ones. But it makes perfect sense that by the time George Bernard Shaw set Pygmalion in his own, Edwardian moment, this technology — this medical science! — would have gotten tangled up in all sorts of meta-narratives about love, money, and class. How much is a woman worth, and what changes if she speaks differently? That’s what Pygmalion and My Fair Lady are about.

The contrast between the intended, therapeutic purpose of the Bells’s phonetic science and the ludicrously sudden, drastic change in Eliza’s voice is stark. She spontaneously learns how to speak like a real life duchess after digesting a big, pedagogical speech by her toff benefactor. Sylvestra, by contrast, just cracks open a beer and takes a sip — presto, the same effect. It is a chemical reaction in both cases.

The idea of a sip of beer altering somebody like this is funny because it shows up the rottenness at the core of Higgins’s speech that “inspired” Eliza so radically — not only is it scientifically ridiculous that a pile of bunkum sentiment would wreak such vowel changes so suddenly, but that very fakeness points to the falsity of the sentiment itself. His speech isn’t about anything particularly high-flown or noble: It is an ultimatum. Either Eliza will “conquer” the “majesty and grandeur” of the language that people who matter speak, or she won’t. If she doesn’t, she’ll stay poor. How much is a woman worth, and what changes if she speaks differently?

The Heineken ad satirizes every single one of these notes: The riches-to-rags structure makes rags-to-riches stories look stupid and hackneyed; the avuncular wide boy in the ad makes Henry Higgins look like a lecherous headmaster; the faux-school sends up the British obsession with elocution training. But the fabric of the verbal joke itself — the “water in Majorca” bit — is the absolute cherry on top, and it takes a bit of explaining.

Majorca (also spelled Mallorca) is, as you may or may not know, a popular holiday destination for British people that is cheap, cheerful, and sunny. Long ago, a classy dame going on a grand tour of Europe might say “Spain” with cut-glass vowels, but, by the mid-eighties, the Balearic islands were firmly colonized by British tourists, so at the time of the ad’s production, a posh bird would never dream of going on a package holiday there. There’s even a little nod to the fact that Majorca is basically just a British seaside town, except for the tiny cultural details that a Brit just can’t replicate abroad: the rain in Spain may fall mainly in the plain, but the water doesn’t taste right. Best to stick to beer, since the water in Majorca don’t taste like what it oughta!

So, the ad’s joke relies on the movie it takes the piss out of, but it also (simultaneously!) pivots around a social inversion borne of the great post-war intra-European tourism boom. Posh people don’t have all the fun any more.Thomas Cook, the travel entrepreneur whose company still organizes holidays for countless Britons every year, arranged the first cheap package outing — a train trip with food included between Leicester and Loughborough — in 1841. By the late nineteen fifties, a hundred years of innovation in the business and technology of going on vacation culminated in the transportation of millions of Brits to Spain on cheap flights. The name “Costa Blanca” was literally invented by British European Airways to promote their flights to the coast of Alicante. Leisure time had once been the preserve of the non-working classes, but no longer. Eighties Majorca belonged to the British working class.

But what about the basic premise of a joke at the expense of a posh twit? Very simply, working-class people were valorized on English TV in the eighties. The drawing-room comedies of Noël Coward and Terence Rattigan were long dead, and representation of people who talked normally was newly abundant. Dad’s Army, Rising Damp, Only Fools and Horses — all these wildly popular and influential UK comedies depicted smart, working-class people making posh people look stupid. This was gentle humor: as Hugh Laurie pulled off so well in Blackadder, the poshos of eighties UK comedy are just sort of adorably clueless. The bird in the Heineken ad is from another era — trading in her class credentials for a bit of street credibility might be good for her look

Does it kill a joke to pull it apart like this? I guess that for most Americans, it is funny simply because English accents are a charming anachronism, the leftovers of a quaint, dead world — like imperialism and pocketwatches. But I’m an English person living and working in America, and I think about what my voice means every day. Why are some of the things I say funny, others merely incomprehensible? Why is this ad funny to the New Yorkers I’ve shown it to, but I have never seen an American laugh at Shooting Stars? I’m not really interested in the ins and outs of how American and English cultures differ. It doesn’t annoy me when an American repeats something I’ve just said back at me in a shitty version of my accent. But it does interest me to know that the very timbre of my voice can intimidate, or seem stuck-up, and that I can’t predict when or where that will happen.

As I see it, the sound of a British voice lives in American culture in a sort of disorganized state of decay, a weird half-life where voice features like accent and vocabulary become hard to interpret. Nobody can tell where I’m from or what class I belong to, but they know they’ve heard my voice before, in a movie, perhaps — or maybe an ad?

The Heineken ad is about the politics of voice. My Fair Lady just symptomatizes them. It is a terrible film, in fact; maybe even a nasty one. They don’t even kiss at the end! Ugh. If the movie has a redeeming moment, however, it is Jeremy Brett (as Freddy Eynsford-Hill) singing about the street Eliza lives on. By the time of the Heineken ad, a very ill Brett was visibly deteriorating in front of the British public who loved him, struggling on as a lithium-bloated, waxen-faced Sherlock Holmes. But in My Fair Lady he is young and glowing and lovely, and I’d watch it a hundred times just to look at him. So, let’s forget all about Henry and Eliza and the horrible history of British accents and instead let Freddy sing us out, dove-grey top hat and all: