The City That Split in Two

by Mae Rice

Last month, police in Gary, Indiana found a woman’s body in an abandoned building. When they apprehended her alleged killer, Darren Deon Vann, he confessed to murdering her and six other women and hiding their bodies amongst the some ten thousand empty buildings strewn across the city.

Gary, which was founded as a company town by U.S. Steel in 1906, has slowly amassed these abandoned buildings since the early sixties, when the city steel plant laid off thousands of workers, beginning a long, ongoing process of atrophy. In 1968, when the city elected its first black mayor, Richard Hatcher, a tidal wave of white flight compounded the exodus. A civil rights leader, Hatcher was one of the first black mayors of a major US city, and spent twenty straight years in office.

Today, Hatcher still lives in Gary. He’s eighty-one now, with a sharp, wonkish recall of town history and politics. We talked on the phone about the abandoned buildings’ backstory, and what white flight looked like when he was mayor: less like flight, and more like secession. In 1971, whites from Gary created Merrillville, a new, separate town on Gary’s Southern edge. More than forty years later, it’s still whiter than Gary — forty-six percent to Gary’s eleven — and more prosperous — a forty-six-thousand-dollar median income to Gary’s twenty-six thousand dollars.

Gary’s abandoned buildings have gotten a lot of media attention recently, with the serial killer case. In your view, what’s the story of how they came about?

It’s important to understand what has happened to our city. Once I was elected mayor, and as blacks in Gary gained more political power, whites began moving out of the city. That was not limited to the average white citizens of Gary. What really did great harm was that the major businesses chose to move out.

Sears and Roebuck had one of the biggest stores in this area in downtown Gary. It closed that store and built a new one in Merrillville. We tried to stop them. There were demonstrations, people tearing up their Sears charge cards, and all of that. But they said the people — and they were obviously talking about whites — were moving south. Before these commercial businesses left in the early sixties, we’d also had this problem with our real industry, United States Steel. They’d had this huge plant in Gary that employed more than twenty thousand people. They decided to adopt the technology that the Japanese had been outcompeting them with, and suddenly those twenty thousand jobs went down to seven thousand, which is what they have out there today. Now, the managers boast that a steel ingot can go through the whole plant without touching human hands.

How would you weigh white flight’s role in this? Was it a major factor? More cosmetic?

If we’re going to talk about “white flight,” we should understand what we’re talking about. Generally, when people use that term, they think of it as white citizens who choose not to live in proximity to black citizens. But the part of white flight that has been most damaging to Gary is that we have been colonized, in much the same way many African countries were by the British and the French. The latest estimate that I’ve seen is that our police department is close to sixty percent policemen who live outside of Gary, and most of them are white. They are the ones who are supposed to protect and serve the people of Gary.

The protests in Ferguson must hit close to home.

Yes. The thing with us is, the same is true of the fire department. At least fifty percent of the firemen in Gary live outside the city. A recent study said that of the twenty-four thousand public service jobs, seven thousand of the people who hold them live in Gary. And citywide, Gary does not have a lot of industry. Public service jobs are some of the best jobs that you can get, and yet ours are held by outside people who pay no taxes to Gary. That’s devastating. So you say, why does Gary have abandoned buildings? It’s easy to understand.

Let’s talk about white flight to Merrillville, specifically. To give a sense of scale, I’m curious how many people from Gary, all told, left to go to Merrillville?

One way to measure that is to look at the number of people that were living in the city while I was mayor, and the number of people that are living in the city now. That would be maybe a hundred and seventy-five thousand people while I was mayor, and today, about eighty thousand.

So about ninety-five thousand people?

Well, everyone didn’t go to Merrillville, but the vast majority did. And now, as black people move to Merrillville, whites are moving even further South. Lowell, Jasper country. They just keep running.

How did Merrillville get founded?

So Indiana had this law — the Buffer Zone Law. The law was that you couldn’t incorporate a new city or town within three miles of an existing city or town, to make sure cities had room to expand. One state senator named Adam Benjamin — he was actually elected from Gary — and a state representative, they went and got the state legislature to pass this law that eliminated the buffer zone around Gary.

Just the one around Gary?

Yeah. Indiana’s got a constitution, which says you can’t pass special laws for one city, one town, etc. But they got around that, because instead of saying, “We want to eliminate the buffer zone around Gary,” they said, “We want to eliminate the buffer zone around a city that has a river that runs through it, and that has a steel mill…” and by the time you got down to it, there was only one city in the state that fit that description.

They eliminated that, and formed the town of Merrillville.

As mayor, how did you handle the foundation of Merrillville? I’m curious if you tried to woo the departing whites back at all, and just in general how you responded.

How I responded? I talked about it too much. I was accused of being anti-white. I heard that every day, because I would argue that this is not good for the people of Gary. And since the people of Gary were becoming predominantly African-American, they said “Oh, he’s just for black people.”

To answer your question, I thought it was wrong, and I always opposed the creation of Merrillville. I would go down to the state legislature and meet with the governor and put what I thought were very logical arguments on the table.

What sort of arguments?

I explained to them that, first of all, it was unjust to eliminate Gary’s buffer zone, and leave all the other buffer zones around the state intact. I said that was discriminatory. And since Gary was the city with the highest percentage of African-American citizens, it would appear that you are discriminating against black people. I also tried to make the argument that even if whites’ feelings of racism were so strong that they wanted to move out of Gary, because it has a black mayor — even if that was true — they would have had no place to move, unless they moved a long ways away, and that could be very expensive. But by creating this repository — I call it a repository of racism — called Merrillville, that gave people a place to go.

Remember, the infrastructure of Merrillville was not paid for by the people who moved out there and built houses. The federal government provided the highways and so forth that allowed people to move to Merrillville and still work at US Steel. Which many of them to this day still do. Our tax dollars — they wound up helping whites flee.

Did whites and businesses have any story for why they were leaving, besides that they didn’t like black people?

Well, literally from the day that I took office, there was a systematic effort by the news media to demonize the city of Gary. The largest newspaper in Gary, the Post-Tribune, it was a daily drumbeat, of “there’s so much crime in Gary.” Those of us living here said, “Yeah, we have some crime. Most cities do. But it’s nothing like what the Post-Tribune is putting out there.”

It’s kind of obvious to me that what that did was justify the whole idea of moving to Merrillville. While I was mayor there, this one very popular commentator on the radio station, he came on one morning and said in a very dramatic tone: “A little old lady was viciously attacked and beaten and Mayor Hatcher had no comment.” And then he paused for a moment, and he said, “And this happened in Seattle, Washington.” It was incredible! Anything that would reflect in a negative way on me, on the city itself, the news media at that time played it to the hilt.

That was sort of the way it was. When these things were happening here in Gary, and as blacks began to be elected mayors of other cities around the country — Detroit, Philadelphia — the same patterns repeated. For example, I used to think of Detroit as this great place. They make cars! But now, how do you think of Detroit? A failed city, almost. Well, that was not by accident. This has happened, as minority populations have expanded in these urban areas, you have seen a complete reset of the attitudes.

What was going on in the Gary community while Merrillville was getting founded, and white people were leaving? Were there hurt feelings? Did you hear about friendships ending between people who stayed and people who left?

Well, there’s an area in Gary called Miller that sits right on the shores of Lake Michigan. That’s where our beach is, and that whole area is a nice place to live. Lots of greenery. Many white people who chose not to leave Gary lived in Miller, and they stayed in touch with the Merrillville folks.

And many of the people who have moved to Merrillville more recently — they are black! They come to Gary for church even now. There’s communication.

So relations aren’t terrible.

When Merrillville first came into being, many people took an attitude like I did. If I was invited to something in Merrillville, I wouldn’t go. Shortly after becoming mayor, I was invited to this hotel in Merrillville to give a speech, and when I got there and I was looking around for the room, this waitress — she was absolutely a waitress — was walking by and she asked me, “What are you doing here?”

It should not have, but that really cut me to the bone. She thought I had no right to even be there. So after that, I wouldn’t go. Then some members of the news media got angry at me. They said, “That just shows he’s anti-white.”

What do you think the whole founding of Merrillville says about the democratic process?

Oh, I think it was a complete failure of the democratic process. It was in the Indiana State Constitution that you had to have this buffer zone, but there were enough people on the legislature who thought, “Hey! The buffer zone around the city where I live, we need that. But the buffer zone around that city” — which at that time everyone was looking at as the only black, quote-unquote, city in Indiana — “yeah, it’s okay to take that away.” That clearly was a racially motivated act.

It’s so fascinating to hear all of this discussion about the last election, and why the Democrats lost so badly. None of the commentators mentions racism as being a factor. But in Gary, racism clearly trumped democracy. There is no question about that.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

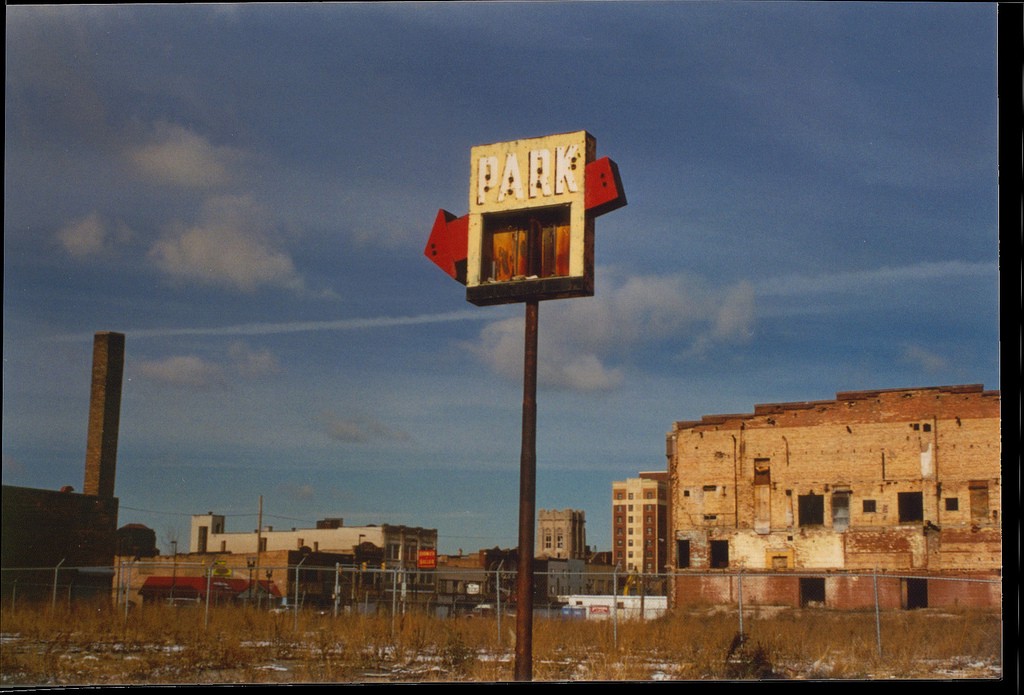

Photo by Samuel A. Love