Pushcart New York

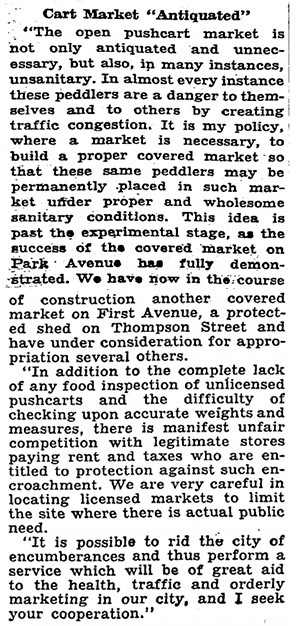

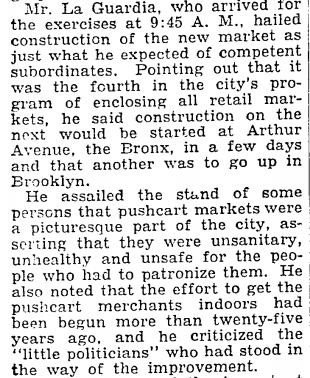

In a 1938 New York Times story, then-mayor Fiorello LaGuardia laid out the case against pushcarts. The street vendors, which were not as diverse as they were in pre-car New York but which still sold a wide variety of goods, including food, were an unlicensed liability to the city and its residents. They were a threat to “traffic, health and sanitation.” He said they were a holdout from a bygone era; he didn’t quite say, but meant, that they were evocative of tenements and rag sellers and How the Other Half Lives.

The plan for the Lower East Side was to replicate the city’s recent success with indoor markets. These places got vendors out of the way, and created, for residents, a sort of urban indoor mall. Normalizing these indoor markets would limit and possibly stigmatize outdoor vendors, or at least make them easier to police. The article describes a plan that eventually came to fruition as the Essex Street Market: “The department is also developing plans for placing the street peddlers in Orchard and Rivington streets in city-owned property on Essex Street, between Broome and Houston Streets.” You can see the city’s renderings for the buildings here. They’re not far from what was actually built, and remains today.

Demolition of a currently vacant building at “Site 2” is set to begin this month. Here, you can see a set of renderings for the building that will replace it, or at least part of it: a 26-story tower anchored by a movie theater.

The greater development, called Essex Crossing, will encompass existing buildings and nearby lots that have sat empty, used as parking lots, for decades. When it was announced, the deputy mayor described it like this: “This project is the pinnacle of urban development in 2013. It has all the hallmarks of a Bloomberg administration project: transforming an underutilized asset into a place that serves the diverse needs of the community.” Essex Market will move across the street to a larger, newer venue, where vendors have been promised stable rents, but where they will be joined by a supermarket. Right now, Essex Market contains a strange mixture of groceries, pre-prepared foods, expensive new indulgences and rare bargains. It’s a delicate ecosystem. It can be moved, but maybe not preserved.

Over the last ten years, the city, with the help of large developers, has been trying to solve the problem of street vendors once again. Instead of meeting the needs of an urban underclass, either through labor or goods, new vendors mirror the desires of a specific urban overclass. They are slick trucks, not carts. They serve lobster and ramen burgers; recently, Amazon rented a food truck to sell Kindles. This time around the city’s concern is less about traffic and filth and oversight than it is about convenience — the “problem,” today, is that the street vendor market opportunity is not being fully exploited. In 1940, a cluster of street venues was a scourge, and any nostalgia for pushcarts was misplaced:

If you throw a dozen vendors together today, you have a rally. Get a few dozen, and you have a New York-inspired food theme park, conveniently located just over the Williamsburg Bridge.

This post has been corrected: The building that is set for demolition this month is currently vacant.