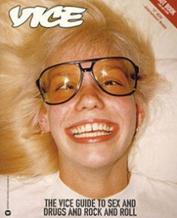

The Lessons of Vice

A post-mortem on pre-mega-expansion Vice, by Alexandra Molotkow:

The magazine was a point of intersection for a number of subcultures that started balling together around the turn of the century. It’s hard to say what this scene was about, exactly: clothing-wise, Vice “style” was defined negatively — the Don’ts were always funnier than the Do’s — so it was more about what you couldn’t wear (dreadlocks, sandals, pubes) than what you should. Musically, it was far-flung, though artists like Andrew WK and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs were staples, and I remember it as a leading champion of electroclash. Coke was the drug of choice, but in drugs as in all things, Vice was omnivorous. It was ahead of its time that way; the end of genre boundaries and style tribes — along with a new emphasis on sensibility over taste — is probably the most distinctive attribute of “youth culture” after the Millennium (and part of what makes a “hipster” so hard to identify).

That this piece is thorough and lucid and yet still leaves you disoriented is a testament to how inseparable the old Vice product was from its burbling sensibility; now but especially years from now, people will not remember issues of the magazine, or stories, so much as periods and places in which Vice just felt very present. The new Vice is conspicuously substantial, its output easier to point to, categorize, and put on a timeline. The most enduring product that old Vice produced was an enormous and marketable demographic. It was assembled from countless odd subcultures; its glue was insecurity (and maybe music and maybe drugs, a little). Apart, they were slippery and defied naming. Together they formed a cohort, fell into line, and became pitchable.