The Homeland Generation

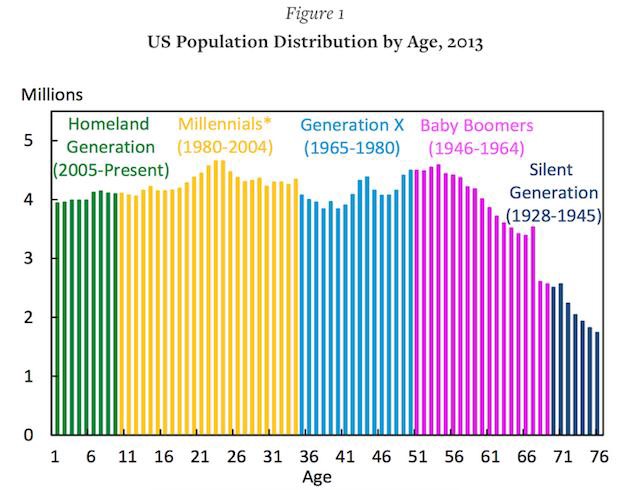

This is Figure One in a document published by the White House, on Medium, called “15 Economic Facts About Millennials.” It is included to establish a premise for the post: that the “Millennial generation will continue to be a sizable part of the population for many years.” It seals off that generation at 2004, which means the next one begins at 2005. The next one is labeled without explanation: The Homeland Generation.

This data is credited to the Census Bureau, but presumably only the raw population numbers — the “Homeland Generation” is not, apparently, an official census designation. The choice to use it, then, fell to the people handling communications for the White House.

These people would have been presented with a number of options, none of them appealing: Generation Z. Post-millennials. Plurals. These are early and over-eager names concocted by marketers, and it is obvious. Gen X didn’t know it was Gen X until it was teenaged; the first millennials were old enough to roll their eyes at the term as soon as people started using it earnestly. Coinages are deliberate. Winners are decided in retrospect. There was no need for the White House to use a distinct name, here, except to fill a blank label in a chart. Not the current administration’s problem!

This was what a political operative might call an unforced error. The Homeland Generation is not just an unnecessary choice but a jarring one; its optics are conspicuously clumsy considering that optics are the sole concern of this document. Read it from the perspective of a non-American to get the full effect: The “Homeland Generation” sounds paranoid, xenophobic, and ready to fight. It’s almost like something out of speculative fiction, what a writer might call the first generation of people after some great collapse shattered the modern world into nationalist tribes. It would be very useful in this context — it would convey fear and selfishness and reversion, instantly, to use such a darkly coded word. It’s the kind of name you would give to a lost generation, seeing as the “Lost Generation” is already taken. The reader would get it.

William Strauss and Neil Howe, who are famous for attempting to rewrite history in terms of cyclical generations, are both the most likely people to have defined the Homeland Generation and, as far as I can tell, some of the only ones who have tried:

The name doesn’t have some clever double-meaning, and there’s nothing arch about it. The Homeland Generation is a generation named in language of a terror-obsessed era that it was too young to experience acutely; a generation subjected to crushing surveillance by suddenly and unaccountably insane parents, fixated on their own pre-war-on-terror, pre-millenial childhoods. The Homeland Generation: It’s what it sounds like! The first sentence of the next section in the piece, by the way, which was published in the Harvard Business Review, begins: “If you are a marketer planning the next generation of consumer products or services…”

According to the Strauss–Howe generational theory, which has been most enthusiastically embraced by the marketing community — virtually all other online references to the Homeland Generation are concerned solely with theoretical marketing strategies, sometimes referred to as future “realities” — the Homeland Generation is the first recurrence of a “suffocated” generation that is “entering YOUTH” since the Silent Generation, which, according to their boundaries, left youth in 1946.

(In case you’re tempted to place stock in this unfalsifiable grand unified theory of generational cycles, something to reckon with: this model categorizes both the “GI” generation (1908–1929) and Millennials as archetypal “heroes.”)

The “Silent Generation” name caught on after a Time essay in 1951:

Youth today is waiting for the hand of fate to fall on its shoulders, meanwhile working fairly hard and saying almost nothing. The most startling fact about the younger generation is its silence. With some rare exceptions, youth is nowhere near the rostrum. By comparison with the Flaming Youth of their fathers & mothers, today’s younger generation is a still, small flame. It does not issue manifestoes, make speeches or carry posters. It has been called the “Silent Generation.” But what does the silence mean? What, if anything, does it hide? Or are youth’s elders merely hard of hearing?

The piece is a vague and fascinating attempt at categorization. It does, at least, include the voices of its constituents. It reads as an earnest attempt at understanding. It’s also bleak as hell: “The fact of this world is war, uncertainty, the need for work, courage, sacrifice,” the writer concludes. “Nobody likes that fact. But youth does not blame that fact on its parents dropping the ball. In real life, youth seems to know, people always drop the ball. Youth today has little cynicism, because it never hoped for much.” These kids were born during the Great Depression.

Defining a generation in retrospect gives history order; defining it in real-time is really an act of prediction. That’s why marketers are so interested in doing it: They are speculators. The White House report, which is otherwise an exhaustive catalog of things supposed in the press about Millennials, does the speculators a favor — it raises the stock in one possible ticker symbol. (A speculator might say: It’s even better that it seems like an accident. Someone in Washington just Googled “what comes after Milliennials” and this is what they found? That’s not nothing! It’s a sign of the strength of the brand.)

The report also gives Millennials pretty good odds:

So, while there are substantial challenges to meet, no generation has been better equipped to overcome them than Millennials. They are skilled with technology, determined, diverse, and more educated than any previous generation. Millennials are still in the early stages of joining and participating in the labor market.

But the Homelanders? It’s already too late for them.