Intimate and Anonymous: Alejandro Cartagena's 'Carpoolers'

by Jon Michaud

The Art Museum of the Americas stands at the junction of Virginia Avenue and 18th Street in Washington, D.C., just a few blocks from the White House, the Washington Monument, and the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. The red-roofed Spanish colonial villa that houses the museum is a sort of in-law residence annexed to the palatial Organization of American States headquarters (also known as the Pan American Union Building), which occupies the 17th Street side of the same block. A well-tended public sculpture garden featuring the busts of pan-American statesmen and writers separates the two buildings. There are no fewer than four statues of Simón Bolívar on or near the grounds, as well as castings of Pablo Neruda, Abraham Lincoln, José Martí, Gabriela Mistral, José Cecilio del Valle, and Gabríel Garcia Marquez. Walking among those art works assembled in the name of inter-American unity and cooperation is a melancholy experience; such aspirations are so out of synch with the current political reality that I half-expected the plaques on the statues to be in Esperanto.

What brought me to the AMA was a show by the photographer Alejandro Cartagena, titled “Small Guide to Homeownership.” Cartagena, who was born in the Dominican Republic but lives and works in Mexico, certainly fits the pan-American mold. The exhibit begins humbly enough, with a looping black and white video of the entrance to a 2010 “real estate event” in Mexico: Potential home-owners wander in an out of a doorway marked “Buscando Casa” as music plays, depicting the banality of the consumerism that drives the continued expansion of the outer suburbs of Monterrey, Juarez, and Apodaca (not to mention Atlanta, Las Vegas, and Washington, D.C.).

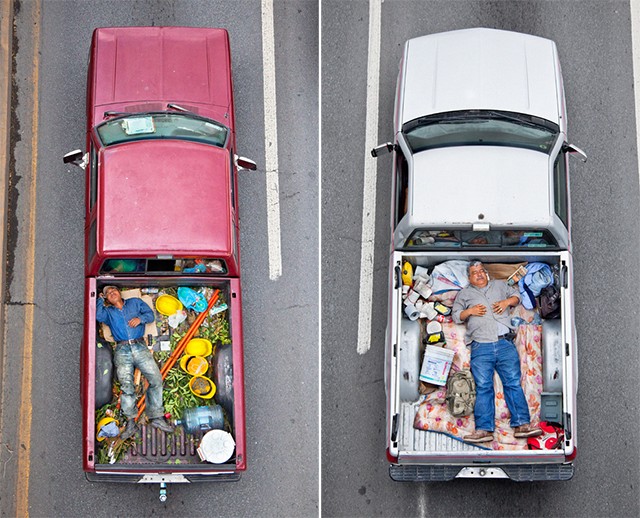

But all of that was prelude. Thirty startling images from Cartagena’s “Carpoolers” series, taken in 2011 and 2012, comprised the rest (and best) of the show. “Carpoolers” is a found poetry of terrific power: Twice a week, during the morning rush hour, he set his camera up on a pedestrian overpass above Highway 85 in Monterrey and took bird’s-eye-view images of day laborers in the backs of pickup trucks on their way to cut lawns, plaster walls, and excavate swimming pools in the city’s wealthy neighborhoods. Intimate yet impersonal, voyeuristic yet respectful, the photos offer glimpses at men who are usually overlooked or hidden from view. “I was very excited when I found these workers going to work this way,” Cartagena told me in an email. “I had been looking for a way to represent the people who had bought the small suburban houses and how they were managing going to work every day.”

All thirty photographs share the same composition: an overhead view of a truck. The truck appears to be driving vertically, up the wall of the museum. On either side, you can see the blacktop and the lines painted on the road. Sometimes a bare elbow pokes out of the passenger-side window. On the truck’s dashboard there are clipboards, folded newspapers, and plastic food containers. The vehicles are interchangeable for the most part, but the eye keeps getting drawn down to the rectangular pickup beds. In one photo, a young man lies on his back, arms folded across his stomach, his body parallel to a row of wooden beams. He looks as stiff as a piece of lumber, eyeballing the viewer suspiciously. In another, five young laborers lie crammed into the space like shipwreck survivors sleeping on a raft. A third shows two men reclined next to piles of cabinetry, staring up at the camera with smiles on their faces, as if they have just been caught plotting a practical joke. In several cases, the human passengers are not immediately identifiable; they are hidden under blankets or sheets of cardboard, just another piece of cargo sharing space with ladders, wheelbarrows, buckets, shovels, brooms, and rakes.

Stare at these pictures long enough and the truck beds and their contents will transform. Suddenly you are looking at a dumpster in which a dead body has been tossed; a potter’s grave sprinkled with lye; a bed in which one spouse sleeps contentedly while the other grumpily reads a newspaper; a social club with nearly a dozen men sitting in a circle talking companionably. In one of my favorites, the bed resembles a tropical salad: green, lettuce-like hedge trimmings, the carrot-colored orange poles of the landscaping tools, the upturned yellow hard hats like hollowed out mangoes. The prone, denim-clad workman is a splash of blueberry vinaigrette. In yet another, a man wrapped tightly in a colorful Mickey Mouse blanket could be either a sleeping, overgrown toddler or a mummy unearthed from the peat bogs of Ireland.

By excluding all context beyond the sides of the trucks, Cartagena’s photographs invite interpretation and speculation. Is traffic moving or not? How loud is it? Where are they going? We can only guess. The viewer begins to wonder about the social hierarchy among the men in these trucks. Is there a pecking order? Do they rotate who gets to sit in the comfort of the cab? Is banishment to the truck bed a form of bullying? Do some of the laborers prefer it so they can catch a nap? Cartagena’s pictures tread the line between the uncanny and the mundane, the private and the anonymous. He urges us to ponder the lives of people many of us would rather not think about.

The show at the AMA closed in September, but Cartagena has recently gathered a hundred and twenty-seven of his Carpool pictures into a book of the same name. The volume, which features many photographs that have never been exhibited before, can be purchased only through Cartagena’s site. “The book covers almost all the pictures I think of as the whole project,” Cartagena told me. “The construction of the book makes some of the images just work on a page and not on the wall.” The photographer, meanwhile, continues to work on his overall project of documenting the transformation of Mexico’s cities. His next series, he says, will examine the ways that the country’s rapidly expanding suburbs are transforming the existing infrastructure of its cities. It may sound like a lesson in urban planning, but “Carpoolers” gives us ample evidence that Cartagena will find a way to make this subject compelling and human.

After more than an hour in the exhibit, I walked back though the gardens to get a closer look at the Pan American Union Building. There, near the corner of 18th Street, I came across a team of landscapers who had spent the morning working on the grounds of the O.A.S. headquarters. Looking like they had stepped right out of Cartagena’s photographs, the men were taking their lunch break under a tree. Two were talking in Spanish and laughing. One was reading a newspaper. Another was sleeping. The fifth was thumbing nervously at his smartphone. Nearby, in the driveway, was their truck. I couldn’t help but notice that it had a double cab, large enough to accommodate all of them.

Jon Michaud is a novelist and blogger, and the former head librarian of the New Yorker. His most recent novel is When Tito Loved Clara.

Photos copyright Alejandro Cartagena. Used with permission. Carpoolers is available now.