Intern Deluxe: The Rise of New Media Fellowships

by Eric Chiu

My first unpaid media internship was in the summer of 2010. Like most college students, previous semesters spent whiffing on applications made landing one feel like a reward, regardless of pay — I’d move to New York and even have the chance to write (mostly) professionally. The “unpaid” part always loomed, but my friends and I made it work through varying levels of cost-cutting and couch-crashing. Besides, we were all believers in that age-old internship axiom: As stressful as working for free was, we’d be getting the experience and exposure needed to compete for real, paid jobs. The problem with “climbing up to minimum wage” as an employment strategy never really crossed our minds.

Unpaid internships, long a due-paying rite of passage for college students, became entrenched as a stopgap solution for employers with spots to fill but without the money to properly fill them. This was (and is) very bad. In cases where full-time work was carried out under the auspices of internship programs, it was also illegal. And, as the ways that many unpaid internships violated labor laws became common knowledge, former interns began taking their employers to court. The earliest lawsuits, filed around late 2011, challenged the argument that interns weren’t technically employees and didn’t qualify for protections like minimum wage because they were getting educational or professional benefits by being in the office. After a federal judge ruled that Fox Searchlight Pictures was illegally using unpaid interns on the movie Black Swan in June 2013 — the first major ruling against unpaid internships — a wave of lawsuits followed against media companies like Conde Nast, NBC Universal and Gawker Media. (A similar case against the Hearst Corporation, filed in 2012, is currently under appeal.)

The media industry adapted swiftly: Slate began paying its interns in December 2013; Conde Nast shuttered its intern program entirely; and the Times ended its sub-minimum wage internships in March. But other high-profile employers have turned to a new way to temporarily employ students or recent grads: fellowships.

The term is certainly an improvement: Who would want to serve as an intern when they could work as a fellow? The concept is also pedigreed: Fellowships have existed in academia for a while — the Rhodes Scholarship, which started in 1902, purports to be the oldest international academic fellowship program. Traditionally, academic fellowships have been year-long scholarship programs with explicitly scholastic goals that rely on funding from private foundations or nonprofits. These fellows can travel the world or attend universities for research, grad school or work; it’s a far cry from a typical cubicle-dwelling first job. By comparison, most modern media fellowships fall somewhere between an internship and a full-time job, since a fellow gets paid and works just like a regular employee — except that they aren’t.

The Atlantic Media Fellowship Program, which started in 2009, was one of the first of its kind. Outlets including Buzzfeed, the Huffington Post and Wired launched their own fellowship programs between 2012 and 2013. (Though the current boom in fellowships occurred alongside the first round of unpaid internship lawsuits, its participants were largely anticipating, not reacting: Buzzfeed, the Huffington Post and Wired had previously paid interns.) The language of these fellowships gives some idea of what a new prototypical fellow does, and is: Buzzfeed’s fellowships will be “for the next generation of writers and editors eager to master the tools and techniques of the social web,” while Wired and Pacific Standard’s programs target candidates “pursuing journalism as a career” who’ve had “experience working in a deadline-oriented environment.”

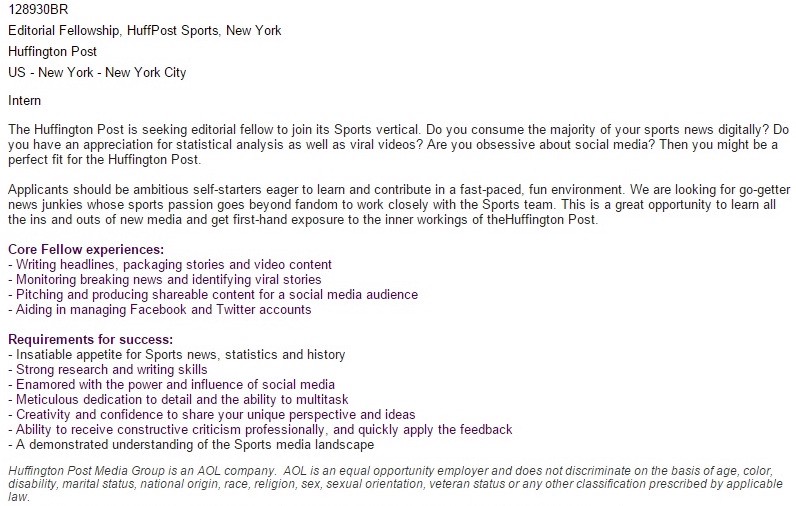

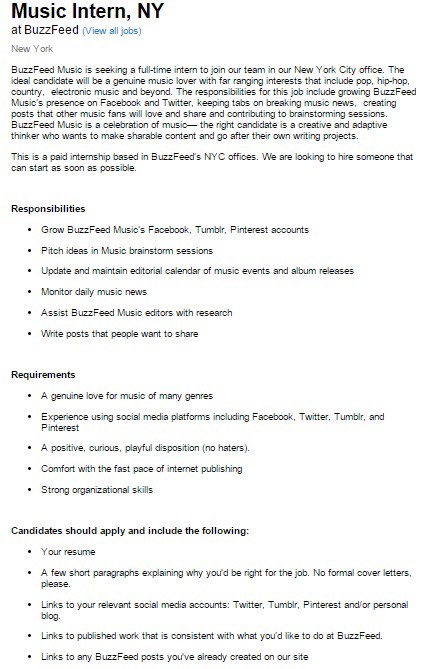

Internally, employers make a point of emphasizing the distinction between fellows and interns, and between both and regular staffers. In Vice’s piece on interns at liberal publications, a Mother Jones spokesperson said that the magazine doesn’t consider its fellows and interns to be employees.1 In practice, these boundaries seem to be more fluid. Ample overlap frequently exists between internships and fellowships, which aren’t always meant to replace intern programs; both coexist within Huffington Post and Buzzfeed, for example. The following job listings from the Huffington Post and Buzzfeed share several bullet points — staffers are expected to pitch, write and follow a beat like any reporter — but the distinction is with each position’s title.

Huffington Post is asking for a fellow; Buzzfeed is looking for an intern. If it wasn’t stated explicitly, would you be able to tell the difference?

A fellow’s typical day-to-day schedule at many media organizations muddles the boundaries between interns, fellows and employees further. At Atlantic Media, fellows are usually recent college graduates who are brought on for a year and placed into a department within the company. (The Huffington Post also places fellows into areas besides editorial departments.) The self-defined nature of other corporate fellowships makes the taxonomy more difficult, but most start from a template similar to The Atlantic’s. For fellows at outlets like Gawker Media or Grist, responsibilities include fact-checking, researching or writing posts, and production, all on schedules similar to a full-time employee’s.

As with internships, compensation can vary widely. Vox Media pays its yearly data visualization fellows a thirty-five-thousand-dollar salary plus benefits, while Mother Jones provides its fellows an initial fifteen hundred dollar monthly stipend. Education is also a part of fellowship programs at Wired, the New York Times and Buzzfeed, which hold regular workshops and seminars for fellows. (There’s no apparent legal relevance to these classes, which are genuinely oriented toward professional development.)

Accordingly, current labor law considers corporate fellowships and internships to be essentially the same thing. The Department of Labor’s six-point internship test plays a role here; its questions determine educational intent and if a position can legally use unpaid workers.

- The internship, even though it includes actual operation of the facilities of the employer, is similar to training which would be given in an educational environment.

- The internship experience is for the benefit of the intern.

- The intern does not displace regular employees, but works under close supervision of existing staff.

- The employer that provides the training derives no immediate advantage from the activities of the intern; and on occasion its operations may actually be impeded.

- The intern is not necessarily entitled to a job at the conclusion of the internship.

- The employer and the intern understand that the intern is not entitled to wages for the time spent in the internship.

According to the Department of Labor, jobs that fail any part of the test “will most often be viewed as employment” and would require workers to be given additional benefits.

In an email, Department of Labor spokesman Jason Surbey said that the organization doesn’t distinguish between internships and fellowships when considering the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and the six-point test. The law doesn’t care. “Whatever you call it — whether it’s an internship or a fellowship — it doesn’t matter what the label is,” Cheylynn Hayman, an attorney at Utah law firm Parr, Brown, Gee & Loveless specializing in employment litigation, told me. “The question is: what substantive work is the person performing and why and what advantage is the company deriving from that person?”

The law considers the distinction semantic, the same isn’t necessarily true of employers, or of applicants. Rebranding has causes. It also has effects. Certainly, some high-profile fellowships have unique advantages compared to internships. According to the coordinators we spoke to at outlets including Buzzfeed, Huffington Post and Atlantic Media, corporate fellows tend to be college seniors, recent grads or graduate students. Finding future employees is an implicit goal for these programs. Huffington Post fellows have responsibilities designed to be like a junior editor’s, ranging from story-pitching to managing social media accounts. Full-time offers are not an assumed long shot. According to Emily Lenzner, vice president of global communications at Atlantic Media, sixteen of the thirty-eight fellows in the company’s 2013–2014 fellows class were hired as full-time staffers. Buzzfeed fellows have also been hired as editors and staffers in various verticals.

If this is the new status quo — cheap but not free labor for media companies, low but real pay for fellows, a nontrivial chance at employment — it’s an upgrade. It’s also important to imagine what kinds of temptations it could create for employers — and workers — in the long term. The modern history of media internships is instructive: As the baseline expectation for internships gradually increased — a 1997 Baffler article imagines a future where you’d “need at least a semester or even a year” of internship experience in order to compete for desirable positions — large, cheap (or free) internship programs were allowed to flourish. In the process, they didn’t stop serving their purposes as training programs, or sources of future employees. They just did so at greater and greater cost to the young workers who participated them — the same workers who needed them more than ever.

Peter Sterne is a media reporter at Capital New York who also runs Who Pays Interns, a site that tracks pay rates for media interns and fellows. For someone searching for a media job today, he says, multiple semesters worth of experience feel like a prerequisite. “At one time, companies would’ve hired people and then trained them,” Sterne said. “Increasingly, these days, it seems that you’re expected to already have skills built up through unpaid internships and maybe a fellowship, and then you get hired based on that.”

Getting paid as an intern or fellow certainly helps, but against the raging garbage fire that is employment prospects for recent grads or students, it’s a partial solution. In February, Buzzfeed’s Doree Shafrir — responding to a New York Times piece about college-aged interns unable to find jobs — proposed a way to solve the problem of permainterns.2 While Shafrir acknowledges that jobs in industries like journalism were never easy to come by, she argues that the market for internships needs to more accurately reflect hiring prospects:

“So now the onus has shifted to people like me, who are hiring them and managing them — and, I think, collectively failing them. When we get internship applications from people who have had three, four, five, or more internships in our field, with no full-time job on their résumé, it is kinder for us to reject them than perpetuate the hope that they might one day break through… I think the solution to this is to reduce the number of internships we’re offering in the first place, pay all of our interns, be more selective about the interns we do hire, and limit the term of an internship to no more than four months… Those of us who are hiring interns should only be hiring people whom we feel we could potentially hire as full-time employees, and we should only hire as many interns as we can have performing meaningful work — work that will help them get hired one day.”

This outlook changes, materially, what an internship is. It also makes clear what it still isn’t: an entry-level job.

Even in a competitive field like media, there at least used to be a coherent farm system for college grads looking for a job. You could start off at a smaller alt-weekly or newspaper and get experience as a staff writer, along with a full-time paycheck. With a staff job, there’s less worrying about where you’ll be, how you pay your bills, and whether you can afford anything much better than catastrophic medical insurance. With these training structures either gutted or burned to the ground, permainterning appeared as a replacement, albeit an inadequate one. The question, then: Are fellowships simply pulling internships up? Or will they eventually pull what’s left of the entry-level jobs down into contract-work limbo?

The novelty of new fellowship programs illustrates just how totally the expected value of these types of short-term positions, from a job-hunter’s perspective, has depreciated. At one time, a college degree and a short successful stint of professional experience might have bumped you to the level of “competitive applicant.” Now, if you’re lucky, it will get you what amounts to a three-month tryout at a company like AOL. You might get the job. You might not. This, you will think, is fine: You received a few months’ pay and a new line item on your resume. And besides, at least it’s not five years ago.

1. While it might seem like a nonissue, the different titles can have potential ripple effects elsewhere.

2. Referring to recent college grads who hop from one internship to another.

Eric Chiu hasn’t been an intern for nearly a year.