The Eternal Afterlife of Lonesome George

by Brendan O’Connor

Lonesome George, likely the most famous tortoise in the world, was the last of his kind. He was the sole remaining member of his subspecies, Chelonoidis nigra abingdonii, from the northern Galápagos island of Pinta. He died two years ago. Last Thursday, his taxidermied corpse was unveiled at the American Museum of Natural History, where he will be on display until early January, at which point he will be moved to Ecuador. “I met George in Paris, walking down the Champs Elysees, in the rain,” Jan, a gray-haired travel and adventure writer, told me. “You can tell I make things up. The coffee is excellent!”

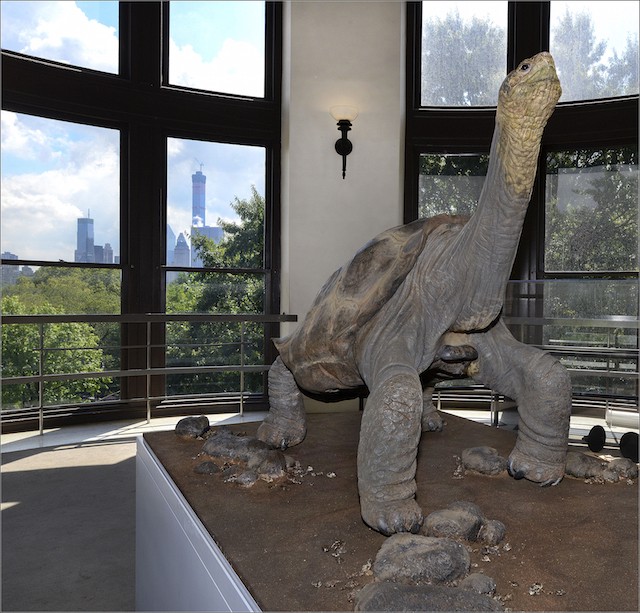

When Charles Darwin landed in 1835, there were at least fourteen different subspecies of giant Galápagos tortoises, accounting for some two hundred thousand individuals. Four of those subspecies have gone extinct, and just twenty thousand Galápagos tortoises remain. The challenge of preserving George’s individuality — while amplifying his symbolism — in death fell to Dr. Chris Raxworthy, the curator of the museum’s Herpetology Department, and the taxidermists from Wildlife Preservations, frequent collaborators with the museum on such projects. “What posture should a tortoise have?” Dr. Raxworthy asked at George’s unveiling. “Tortoises spend most of their lives asleep,” he continued. (Giant tortoises spend up to sixteen hours a day napping.) “That wouldn’t work.” Raxworthy and George Dante, founder of Wildlife Preservation, ultimately decided to pose George with his neck outstretched, as though reaching for a snack. Though it is two feet long, George’s neck, according to the New York Times, is only a size fourteen-and-a-half. He stands alone, as ever, in a glass case at the south-east corner of the museum, surrounded by tall windows. George looks inward, away from Central Park’s surrounding park’s greenery, into a hall filled with the bones of the other extinct creatures memorialized in the Lila Acheson Wallace Wing for Mammals and Their Extinct Relatives. There are green stains on his beak and chin.

For most of the twentieth century — until the discovery of George in 1972 — Chelonoidis nigra abingdonii was thought to have been extinct. However, in 2012, just months after George’s passing, researchers found seventeen tortoises with traces of C. abingdonii DNA on a secluded part of Isabela, another Galapagos island, which might indicate the continued, hidden existence of others of the subspecies. Repeated attempts to get George to breed with genetically similar females over the last forty years of his life were unsuccessful. “We don’t really know what the problem is,” Solanda Rea of the Charles Darwin Scientific Research Station told Reuters in 2001. “He just runs out of steam when trying to copulate. In theory he should be able to mate with the two females we have put with him, but I think that after so many years living alone, he just needs a female of his own sub-species.”

The approximately hundred-year-old tortoise was found dead by his keeper of nearly forty years, Fausto Llerena. “He was like a member of the family to me,” Llerena told the Times when Lonesome died. “To me, he was everything.” His death was unexpected: Giant tortoises often live to be two hundred years old; George’s exact age wasn’t known, but he was thought to be around one hundred years old. An autopsy showed signs of aging in his liver; it is no easy thing, being the last of one’s kind. Llerena, or Don Fausto, as Dante referred to him, is still in Ecuador, and, as far as Dante knows, he hasn’t seen any images of the final taxidermy. “He was in the back of our minds the whole time,” Dante said. “What he thinks, that’s the final word.” As a thank-you, Don Fausto, a woodworker, carved a sculpture of George and sent it to Dante, who showed it to me, cradling it gently in his hands. “This is my Oscar,” Dante said.

George arrived in New York in a state of miraculous preservation, the taxidermist George Dante recalled, having been completely frozen and remaining so over the course of his several-thousand-mile journey. After he thawed, measurements, casts, and molds were taken: what stands in the glass case in the Natural History museum is Lonesome’s tanned skin, stretched over a model. This is an older method of taxidermy, and difficult to get right with reptiles, whose hairless skin offers no room for error; mammal’s fur makes it possible to hide smaller mistakes.

Normally, Dante said, he does not taxidermy pets, because it’s too difficult to capture an animal’s individual personality to its owners and family’s satisfaction. “With George, this is the world’s pet,” Dante said. “The ambition to try to get George to look like George…” he trailed off, ending with a melancholy laugh. Dante and his employees at Wildlife Preservations pored over thousands of photographs and consulted closely with the people who knew George in life to get everything just right. “Not just as a taxidermist, but as an artist, this is the pinnacle of my career,” he said. “I don’t know where to go from here.” Dr. Arturo Izurieta, director of the Galapagos National Park, teared up as he thanked the museum for hosting and preserving George. “He’s not moving,” Izurieta said, “but he is moving our hearts.”

Brendan O’Connor is a reporter who lives off of the L train.

Photos copyright Charles Darwin Foundation/Allison Llerena and AMNH/R. Mickens