'Shy People' and the Consequences of Excavating a Lost Film

by Bobby Finger

-Look over there.

-I don’t see anything.

-You don’t see them. They’ll see you.

Andrei Mikhalkov-Konchalovsky’s Shy People opened in New York and Los Angeles in December of 1987 after winning the award for Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival and receiving a handful of rave reviews. The film was seen by few people and nominated for even fewer awards, even though its lead actors — Barbara Hershey, Jill Clayburgh, and Martha Plimpton — teetered somewhere on the mostly recognizable and well-liked edge of B- and C-list. In May of 1988, the film was given a slightly wider release, allowing it to take one final gasp of air before falling into the murky depths of forgotten films and becoming an official bomb.

Considering the fact that major publications failed to get even its general plot correct in their Fall movie previews, the fate of Shy People was unsurprising — most notably to Roger Ebert.

Of all of the great, lost films of recent years, “Shy People” must be the saddest case. Here is a great film that slipped through the cracks of an idiotic distribution deal and has failed to open in most parts of the country…If you want to see it, move decisively; it will be pushed aside soon by the big summer releases. With slightly different handling, “Shy People” could have been a best-picture Oscar nominee.

Roger Ebert

May 20, 1988

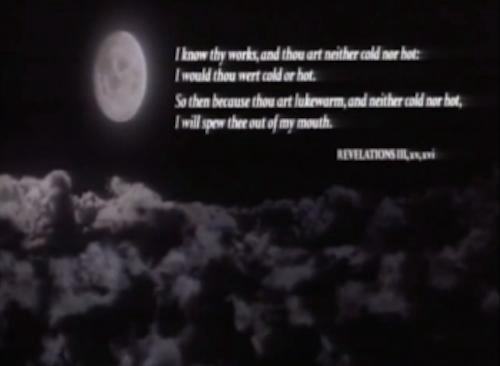

In 2014, Shy People barely exists. It’s only available on Laserdisc, VHS, and YouTube — a trifecta of 4:3 purgatory. The audio sucks; the video sucks; the whole experience sucks. But the film itself is a hell of a thing, even on the smallest of screens. After opening with a hypnotic, three-minute tracking shot through the streets of midtown Manhattan — one of the only parts of the film that the critics unanimously enjoyed — we meet Diana (Clayburgh), a staff writer for Cosmopolitan, and Grace (Plimpton), her rebellious and coke-addicted teen daughter who also happens to be sleeping with Diana’s ex. In an effort to mend their relationship, Diana asks Grace to tag along on her latest assignment: a feature on some kooky distant relatives who live deep in the Louisiana bayou that will no doubt make Cosmo readers giggle. After a lengthy journey through the alligator-infested swamps, they arrive at the home of cousin Ruth (Hershey) and her sons. Mark is a reluctant provider with a short fuse and a pregnant wife (Mare Winningham), whom Ruth despises; Tommy is the handsome one — about Grace’s age — whom Ruth has locked in a cage for reasons that are never revealed; and Pauly is a mentally handicapped gentle giant who’s unfazed by all the craziness surrounding him. The eldest son, Mike, moved away from the compound years ago. “He went to town,” Ruth tells Diana. “That’s dead to me…You’re with us, or you’re against us.” Oh, and Ruth’s dead husband Joe (actually dead, not just in town) haunts the surrounding bayous and keeps the whole family safe. Though the setup sounds like a fairly conventional “city folk meet country folk” narrative (one tackled with significantly more humor that same year in Big Business), Shy People quickly turns into a relentlessly bizarre and maybe-even-a-little-campy examination of life, death, and family.

Hershey’s performance is appropriately off the wall, and her Best Actress award at Cannes was well deserved. Though Ruth locks her son up in a cage, shoots an unarmed man in the hand, and sets a building on fire in the course of Shy People’s nearly two hours, she’s a character we come to sympathize with as her past — like the truth about her abusive dead husband — is slowly revealed. (That said: The winners of the predictably unpredictable festival are decided by its jury, which changes every year. In 1987, its president was Yves Montand, the beloved French actor and, apart from Norman Mailer [imagine Norman Mailer watching Shy People!], the entire jury hailed from Europe, so perhaps it was that perspective that made Hershey’s performance, as well as those given by the four actors portraying her sons, so exotic and appealing. What could be written off as a cheap caricature of an impoverished backwoods Louisiana family in the States might have been seen as something more exciting and believable to Montand and his peers. Or maybe they just respected it as the perfect performance for a Douglas-Sirk-Goes-To-The-Swamp melodrama. [Which is exactly what it is, really.])

Much of the credit for the film’s success in spite of the overwrought melodrama at its core belongs to the film’s production design. Though the characters often feel, oh, less than real, their surroundings are authentic to the point of discomfort. The compound, filmed on location Louisiana, is blanketed by a thick, sticky fog that makes it appear worlds away from anyone who isn’t a ghost. The home becomes a product of the bayou, much like the family that inhabits it.

Despite all of this — an atmosphere you could almost inhale, a collection of unforgettably strange performances, and a genre-bending screenplay — Shy People flopped! It absolutely flopped, y’all. Roger Ebert detailed the shady distribution deal that would make its theatrical run a bomb, but that doesn’t really explain its failure to re-emerge on home video (as well-reviewed box office bombs often do). I suppose it was caused by a combination of little things: a studio that soon went out of business, legal issues involving distribution rights, overall lack of interest, or maybe — now hear me out — maybe it’s not a good movie. What if no one remembers Shy People because Shy People sucks?

Pretend I didn’t write the beginning of this. Pretend you don’t know some sob story about a movie that could have had it all but didn’t. There’s something about watching a forgotten movie — or, more specifically, watching a movie because it’s forgotten — that turns deciding whether or not the movie is good into a tug of war between your normal self and your inner Pauline Kael. The “cult” of a cult movie is primarily one hell-bent on remembering. Being part of a group that breathed new life into a movie no one saw in theaters like, oh, Empire Records will always give the movie’s fans a sense of pride, but it will never change the fact that Empire Records blows. Watching Shy People a second time, I found myself actively wondering whether or not the movie was actually good, or whether I desperately wanted it to be good because life can be so boring and it’s exciting to discover things and I mean come on who doesn’t love rooting for the underdog.

Did that scene where Jill Clayburgh click clacks through Barbara Hershey’s home on the bayou, purse in hand, marveling at the backwoods decor and occasionally checking her hair in a compact exemplify how her performance was a brilliant satire of successful, self-absorbed writers who are unfamiliar with life outside of Manhattan? The first time I watched Shy People, I thought so. The second time I watched Shy People, I just thought Clayburgh was really hamming it up. The entirety of my second viewing was filled with moments like this. Interesting choices were suddenly lazy ones. Brilliant became brash. Dark became gratuitous. And the film’s final shot? Well, I don’t know if I was ever on board.

This is not to say that Shy People isn’t worth watching, I believe it is! Hershey’s performance is a good one, as is Martha Plimpton’s. And it’s always nice to be reminded of what a captivating presence the late Clayburgh always had onscreen. To me, it’s a reminder of how much bigger movies are than themselves. They are the story onscreen + the story of their creation + the story of the first time you ever saw it + the story written by the critic you like + the story written by the critic you hate + all the stories you haven’t even heard yet.

There’s a famous (“famous”) monologue from Sideways in which Maya (Virginia Madsen) discusses why she likes wine. It’s expertly read by Madsen and complemented by a delicate piano piece that adds a nice little touch of melancholy. It’s the best moment of the entire movie. It’s also so on the nose that, when read out of context, it kind of hurts. There she is, comparing a human life to a bottle of wine in a way that lacks an ounce subtlety (it could almost be interpreted as cruel), but it works. There’s something about Madsen + the music + the fact that she lost the Oscar that year (oh my GOD don’t get me started) that adds up to something worth remembering.

Shy People? Meh. The story of Shy People? It tastes so fucking good.

Bobby Finger is a shy people.