How to Say Hello in American

My mother is big on politeness. Recently, before a long trip with my girlfriend’s family, she wrote me a letter outlining the things I should remember to do: stand up straight, hold open doors, and rise when ladies approach the table. “I could go on and on,” she wrote, wrapping things up. “Just please reread the etiquette book I got for you in highschool.”

I did not reread the etiquette book. I trust my own sense of decorum, particularly while on vacation; I’m good at vacations. I’m also a thirty-one year old financially independent human who has lived several time zones away from my mother for over a decade. But a short time after returning from that trip, my girlfriend and I moved from the city where we’d met and spent our entire professional, semi-adult lives, to a different one, across the county, and I wished I had reread it. I’ve come to realize that the thing about moving to a new city and meeting lots of strangers who might, eventually, become my friends — or people I have only interacted with on the internet but are kind of friends there — is that no one knows how to greet anyone anymore.

This is a uniquely American problem. Europeans, and countries colonized by Europeans, have the cheek kiss. In Russia, apparently, the aim is to crush one another’s knuckles when meeting. Japanese people have at least five degrees of bowing. I didn’t know about all of the different degrees until very recently, when the vague and indeterminate methods of American greeting fully crystallized. I was having lunch with an old friend who had just moved back after five years in Tokyo. I asked him what was the weirdest part about returning. “Figuring out how you’re supposed to say hello to people,” he said immediately. He then explained the varieties of bowing, which, honestly, sounded fantastic. What clarity: a nod for those you know well, a little more than a nod — kind of full bow but not quite — for peers, and on down to serious bows for serious times, all the way to the floor.

There is no standard American greeting. There never has been. George Washington’s 1748 “Rules for Civility and Decent Behavior in Company or Conversation” is a good place to start, though it’s really a translation of rules put down by French Jesuits, compiled by a sixteen-year-old Washington. There are many rules about when to speak and when not to speak, when to stand and when to remain seated, and when to shake your head, leg, foot, or eyes. (The answer is never.) There’s also a lot of spit talk: “Spit not in the Fire…bedew no man’s face with your Spittle…if you See any filth of thick Spittle put your foot Dexterously upon it”. C. Dallett Hemphil, a history professor at Ursinus College, writes in his book, Bowing to Necessities: A History of Manners in America, 1620–1860, that the problem with standards of etiquette in the United States has always been about the tension between the aristocracy and the middle-class. Manners first came from and were codified by the elite, who were protected by them; Americans have been anti-elite from the outset, which is probably why our founding father spent so much time discussing what to do about spit.

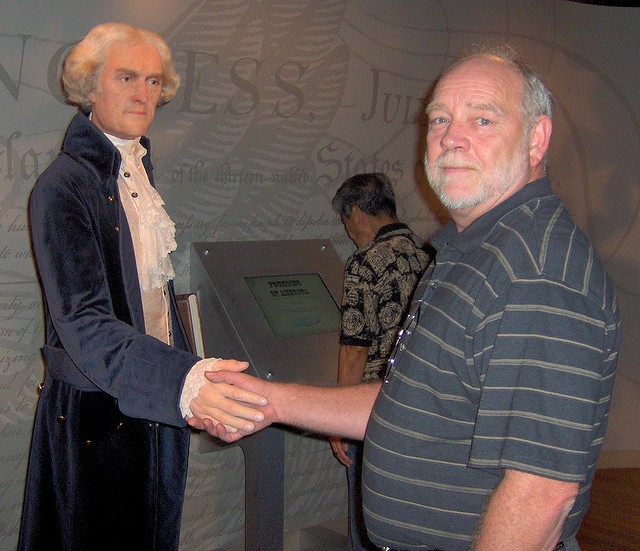

The most thrillingly blunt modern advice on the topic of American salutations can be found on eDiplomat, which gives away some major cultural secrets, like that “see you later” is just an expression; people say this even if they never plan to see you again. “When saying good-bye, Americans may say ‘We’ll have to get together’ or ‘Let’s do lunch.’ This is simply a friendly gesture,” eDiplomat advises. “Unless your American colleague specifies a time and date, don’t expect an invitation.” As for greetings: “American greetings are generally quite informal. This is not intended to show lack of respect, but rather a manifestation of the American belief that everyone is equal.” The Emily Post Institute also doesn’t give many hard and fast rules here, but handshakes are for everyone, even close friends and relatives, with a hug thrown in for good measure. Awl-pal Juliet Lapidos has weighed in on the hug, particularly for goodbyes, and found them wanting. “There are several hug alternatives, among them: the handshake, the cheek kiss, the wave, the arm squeeze, and the nod. Handshakes seem formal, cheek kisses un-American, waves rather odd. Arm squeezing (warm, but not falsely so) would be a good solution if it weren’t for the danger of getting pulled into something more full-bodied.” She likes the nod, and so do I, but, after further consideration and some trial and error, I want to suggest that the handshake — firm but not too firm, arm slightly extended but not thrust out — is the best and most American greeting we’ve got.

It may be too formal, or it could turn into something more intimate than you bargained for — a hug, perhaps. Maybe it’ll turn it into something more sanitary and snappy, like a fist bump, or that other great American greeting, the high five. Maybe there’s no response from your partner-in-shake and the gesture turns into a cartoonish wave and you’ll both laugh about it later. Or you will never see this person again. Or if you do, you will not care, or remember this moment. That’s the beauty of the handshake. It is but a hand extended. An offering awaiting the other person’s response. One half a handshake is equality manifest: it can become anything.

When I was home, I mentioned the note, and the etiquette book, to my mother. She laughed it off and said it had all been a joke. Maybe. She still is big on politeness, and she almost certainly bought me an etiquette book in high school. I remember all the arguments (she would call them “discussions”) we had regarding the nature of decorum. If you rush to a door to hold it open for a lady, are you really being polite? Or are you merely making a show of it? We agree on handshakes, though, and I intend to follow that, even in this place, Los Angeles, where grown men often dress like nine-year-olds, full-length pants are scarce and sleeves even scarcer. If we meet, I’ll probably put my hand out and smile. Do with it what you will.

Ryan Bradley is a writer and editor newly arrived in a sunny land of children.

Photo by Erin Webb