The Cover Job

by Sharan Shetty

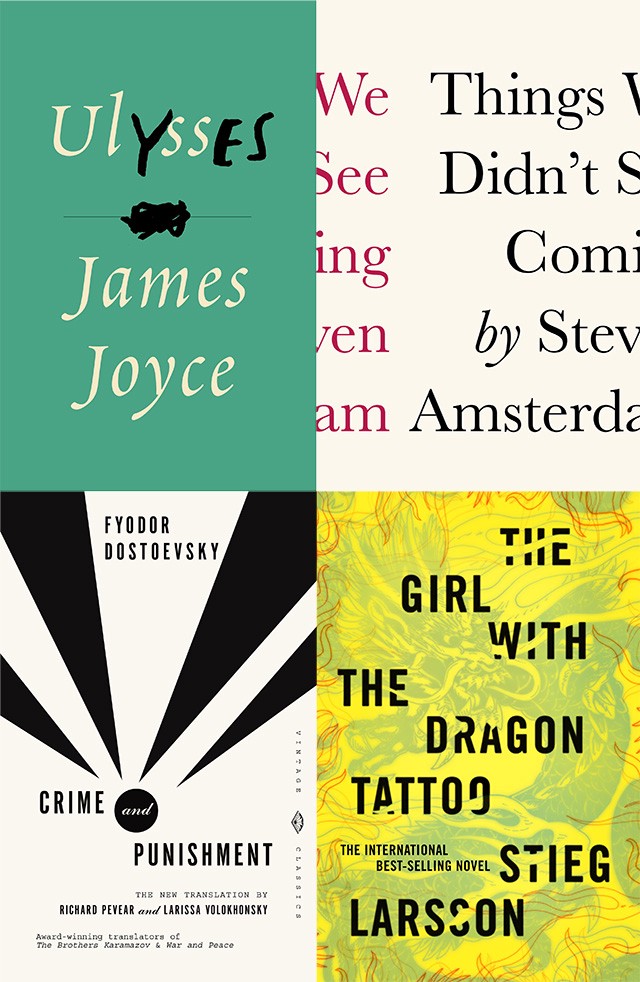

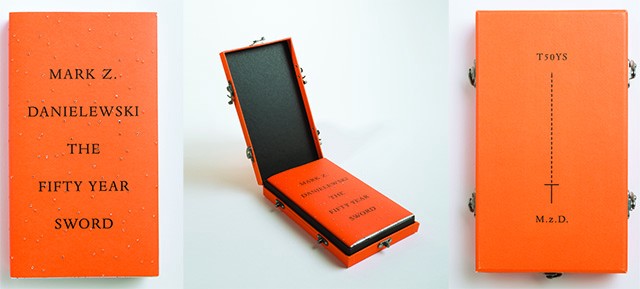

Peter Mendelsund is associate art director of Alfred A. Knopf Books, which makes him perhaps the preeminent expert among those who judge books by their covers. He’s designed covers for everything from The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo to classics by Dostoevsky, Nabokov, Joyce, and De Beauvoir. Last week, he published two books: What We See When We Read, an incisive exploration of the phenomenology of reading, and Cover, a monograph of his best work, which includes his thoughts on designing and several short essays from authors.

I talked to Peter the other day about his work as a cover designer, which began eleven years ago, after a past life as a classical pianist.

So, you were a classical pianist for many, many years, and you mention in Cover that that you still self-identify as such. Is the pleasure you get out of designing at all different than the one you get playing?

Oh yeah, it’s different in kind and degree. The joy I get out of playing piano — there are very, very few things in life that match that particular form of communion. Of course, it’s also hard work, but when it’s going well it’s just one of the great feelings a person can have. If one is playing great music, if you’re playing Bach or Beethoven, and you’re playing it in a way where things are working properly, then your self dissolves, and it’s absolutely a transcendent experience. And nothing, nothing, in design matches that.

It’s not like I’m sitting in front of my InDesign documents swooning. I wish I did. Designing evokes a much narrower range of emotions; that range is somewhere between cool, which is one response, and oh, that’s pretty.

You say in Cover that with book design “clever” and “pretty” are the main benchmarks of quality — that design doesn’t need to deal in profundity. Is that really true, though? Looking at some of your covers, I find profundity. Is that incidental, or do you aim for that?

Well, what you’re trying to do is make something that structurally maps the text. So if there is some unintentional profundity, it has to do with the way the author has written the book and the way the reader has read the book. You’re gonna bring your own experience and feelings to bear on it. I don’t think there’s ever been a moment where I’ve said or felt, “this cover is really profound.” It’s really profundity by association — if it’s a great text, Dostoevsky or whatever, then you connect the experience of reading with the paratext.

You also mention that you can tell at a glance whether a design is working or not. I’ve seen book covers that require a double take, or a look-over, to really absorb. Some of yours, even. Do you relate to that?

The best ones require a double take, and should unfold slowly. It should evolve with the reading. The covers I especially like have tip-offs, so that three-quarters of the way through the book you’re like “Oh, I see.” And the cover sort of then clicks with the text. That’s different, of course, than being able to tell at a glance if a cover works. It’s a different sort of thing. Whether the cover catalyzes with the reader is a separate concern than whether it works on a design level.

I was working on some Calvino redesigns recently, and there were some comps that were funny and pretty, and then there was one that looked a little prosaic. But once I spent a little time with it, it had an element of Easter-egg surprise; it wasn’t static and it seemed to unfold over time, so I went with that.

But how do you avoid the overly clever cover? The punning cover? On-the-nose juxtaposition seems like such an easy trap when designing.

Sometimes winking cleverness is called for, if that’s the tone and affect of the text. And that’s great. I would just say that it’s very hard for a designer not to think in terms of conceptual puns. I don’t know if that’s training or culturation or whatever they teach in the schools — I have no idea what they teach in the schools — but designers really value that idea of cleverness almost more than anything.

It’s a tricky thing to navigate. A lot of these texts that we work on are the result of someone’s blood, sweat, and tears, and the predominant feeling you’re left with after reading is pathos. So, if you then do a cover that’s like “hehehe, isn’t this clever?” it’s a bit tone-deaf. There’s a particular sort of cover that I really don’t like, a sort of punning cover, which is where the cover does the opposite of what the title says. That’s a really common thing. Like if the book is called Thin the type is fat, which is just meaningless and horrible design.

One of the things I like most about your covers are their relative simplicity. Is that a quality you aspire to? Do simplicity and complexity figure at all into your calculus for how good a cover is?

My methodology when I make a cover is to remove elements until I can’t anymore. Frankly, that’s a fault in my process, but I think it’s why you noticed that inclination. It’s great for making simple covers, but there are moments when a text is calling for something really baroque, and I would hope that when that happens I’ll be up to the task. But I think you’re right that it’s a proclivity of mine. I’d really love to do a fantastic maximalist cover, it’s just not my first inclination.

One of your methods is to try to find a single detail that supports the metaphoric weight of the book. How do you know when you’ve found that detail? Is it intuitive or more of a process?

It’s trial and error. The feeling of recognizing that detail in the book is a gut feeling, which comes as it comes to any reader — when there’s a line or moment in the text, and you feel a weight or heft to it, and you think, “There’s something happening here.” Whether that can then be translated into something visual, though, is just trial and error.

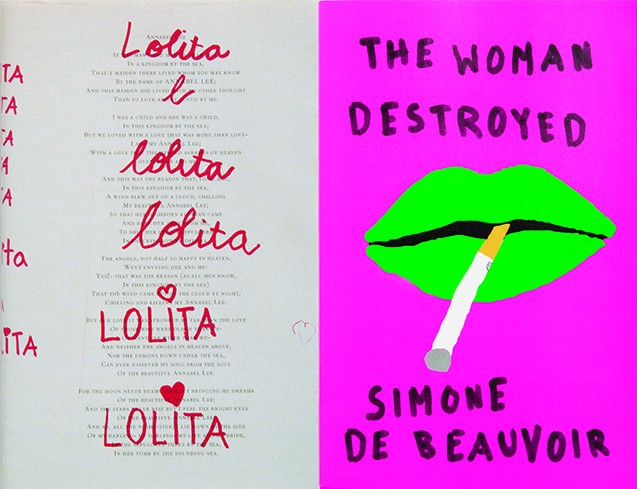

Take your cover for The Woman Destroyed, which I love. How did you arrive at that image, and what was your intent there? It’s so disconcerting, yet utterly effective.

In that case there was also this ancillary, sort of subversive intent. The colors are kind of shocking in their ugliness, and I wanted to do something just for the sheer joy of piquing people. I wanted to do something with a touch of visual ugliness to it.

Right, it’s not classically beautiful at all.

It’s really not, and I intentionally illustrated it in a way that was kind of sloppy. In a way, it was an attempt to illustrate an idea of the text, how society feels toward these broken women, which is just in itself a horrible thing. It’s a commentary on that idea of “we’re done with them, they’re broken.”

One of the things I love about that cover is the abstraction. You mention in your books how abstract covers used to be rare, but they’re now ubiquitous. Is that something you’re happy about?

Yes, for the most part. It’s something I wanted for a long time, and then it happened. I’m happy that it happened, but the part of me that’s just contrarian and impish thinks that if I ever get to design Anna Karenina I’d put a fucking photo on the cover just to mess people up.

But abstraction is a slippery slope, right? Covers can be completely detached from their texts. Or is that alright?

My feeling was always that the minimum bar is, “Can you make something that is not dissonant with your reading experience?” I should also add that I just don’t like book jackets in general. I don’t think I said this in the book, but I’m saying it to you now: I’d prefer if there were no imagery on book covers. But given that we do this, and that we do it with an eye for selling and promoting these books, you could do worse than a cover that just flips people out. The Charlie and the Chocolate Factory uproar that’s happened in the past few days is a great example of that. I really like that cover, which makes me think that I usually really prefer something that’s shocking to something that’s erudite.

What about covers like your Dostoevsky series? They’re just shapes — triangles for Demons, circles for The Double. Is the designing process different for those? They’re so innocuous and open to interpretation.

It’s funny, because at that moment, when I was showing those covers, they were subversive! In the sense that everyone cocked an eyebrow — you know, the general sentiment was like “where’s the painting of the bearded epileptic in Red Square?” There was, in that moment, a little bit of cognitive dissonance with Dostoevesky and suprematism. But once the first cover was approved, and they knew I could do it for the rest of the series, it was just cake. You can’t really go wrong; it’s just so broad and abstract. Those covers speak to the texts in small ways, but they’re really just empty vessels.

So with old classics like the Dostoevsky series, do you feel like you have more latitude with the design? Seems like a different project than designing the cover for a book from the latest unknown in Brooklyn.

The biggest difference for me is that I don’t feel the pressure of a living, breathing author. I don’t need to satisfy them. Which is great, because I feel so bad for these people! To publish a book is just such an intense and exhausting experience, my heart goes out to anybody who writes a novel.

What about the pressure of books — like Lolita, which you talk about in Cover — that are so freighted with imagery and connotation? Do you struggle when trying to escape that visual baggage?

Well, if it’s a book that I really, really love, then in that equation, the pressure is to please myself, and that really sucks. But in terms of a book that — as you put it — has accretions of general visual imagery via all the covers through the ages, that actually just makes it easier. At worst, you know you’re just adding to the pile; at best, what you do can be at the top of the pile.

In general, how do you balance and prioritize the needs of the author, publisher, and readers?

I do think there’s a hierarchy, and that the first responsibility is to the author, which is far and away the most important thing to me. Actually, let me put that differently. The first responsibility is to the author’s text, because the authors themselves are not the most clear-eyed about what the best way to sell that text is. Even setting aside the “selling” aspect, they don’t even have enough distance on what they’ve written to really know how to encapsulate it in any particular way. So the primary responsibility is just representing what the book is, and then after that, the next responsibility is to sell it. Ostensibly, this is a business, and everyone is trying to make a living, so I’d put things in that order. The third responsibility would be to my bosses in the building.

In Cover, Ben Marcus says an author should never interfere with a designer. What are your thoughts on that? Do you ever appreciate author feedback, or is it just a chore that comes with the job?

I’m always wary of it, because knowing a lot about how to write a beautiful sentence doesn’t help you one bit in terms of knowing how to make a book jacket. It just doesn’t. And everyone thinks they have great taste, so my first instinct is always to be a bit wary. But advice from an author is just like advice about anything from anybody — some people are capable of giving you great advice, which comes from a deep well of wisdom, and other people are not so helpful.

You mention in What We See When We Read that when you play the piano, you often miss the mistakes you’re making, just because you’re busy imagining an ideal performance. Does that have an analog in designing? Do you imagine an ideal when designing a cover?

What I do is that when I design something that I like, I’ll say “Good! This is a cover.” Then I’ll print it out, wrap it around the book, put it on my bookshelf, and forget about it. The idea is that I’ll see it peripherally over the weeks, and that’s when I start to learn whether it works or not. Because when you’re working on it, the performative aspect of it takes control, and you start projecting “doneness” on something that may not be done. So that’s one reason I do that; I’d say it’s probably similar to writing. I mean how many times do you write something and say “I AM A GENIUS!”?

Hasn’t happened yet!

Or the opposite! Writing something really crappy, and then coming back to it from another angle. It’s all about getting a little distance and perspective.

When does a book cover’s job end? When it’s picked up? When the book is finished? Is it just a selling point or does it serve a function upon engagement with the text?

The book cover really should unfold over time with the reading experience. When the reader is reading, and the book is over, that’s when it performs its final function. If you finish the book, and maybe even if you didn’t love the book, the cover should still make you want to keep the book, keep it around as part of your life. And more importantly, if you did love the book, then the cover should be something you don’t feel weird about, or something that inhibits the joy of keeping the book around. If it achieves those objectives, then the job is done.

Sharan Shetty is a writer in New York.