Some Things I Will Miss About Brooklyn

by Chris Arnade

On my first day in Brooklyn, twenty-one years ago, I took the subway from my neighborhood, Brooklyn Heights, to its terminus at the tip of Coney Island. I walked the ten miles back, slowly weaving my way through a loose confederation of neighborhoods, held together by subways and buses. Statistically, since then, Brooklyn has changed for the better: It is safer. It is cleaner. But its bumps and edges, the defining features of those neighborhoods, have been smoothed and polished away into an increasingly continuous, glossy surface known as “Brooklyn.” Now I’m leaving.

Pigeon Keepers of Bushwick and East NY

(Pigeons over Bushwick)

On most afternoons, flocks of pigeons swarm above Maria Hernandez Park in Bushwick. They’re owned by pigeon keepers, who breed and tend to them on nearby rooftops. The practice, part sport, part art, was first brought over by Italians in the early 1900s. At one point, well over a thousand men in Brooklyn kept pigeons. About a hundred such keepers are left — mostly Dominican and Puerto Rican men, primarily in Bushwick and East New York. You find them on whichever roofs they can use. A few are lucky enough to own their building, or are supers in buildings with roof access. Most, however, find abandoned buildings with unclaimed roofs and turn them into pigeon homes.

(Young Pigeon Keeper, Bushwick)

The keepers’ stories are almost always the same: Everyone starts young; everyone comes from a rough neighborhood; the birds keep them out of trouble. “I would be dead now if not for my birds. Dead,” Whitey, a pigeon keeper, told me. “So many of my friends are. Birds, they kept me on the roof and out of trouble.”

Kevin, a childhood friend of Mike Tyson’s, started keeping pigeons at eight, while growing up in East New York. “I have had a few problems. Growing up here it’s hard not to, but that’s all behind me now,” he said. “God is now shining his light on me. For the last fiteen years I have stayed away from everything. Now I spend my evenings on the roof with my birds. The pigeons don’t talk back to you and my wife always knows where I am. I can put everything behind me when I am up on the roof.”

Slice was a drug dealer when, at seventeen, he killed another dealer and spent twenty years in jail. Now he is “locked down by my wife and birds. Both of them keep me out of trouble,” he said. “When I am up here on the roof, I am in another world. I can leave all the past behind. All that below us, that’s gone.”

Soccer Tavern, Sunset Park

(Regular in front of bar)

Sunset Park was once filled with Norwegians and other Northern Europeans who immigrated to work the docks along the Brooklyn waterfront. That ended after 1969: The docks started closing, and Norway found oil. Now the neighborhood, especially around Soccer Tavern’s home on Eighth Avenue, is predominately Chinese.

The Soccer Tavern, founded in 1932, is the only straggler left from that period. It is the single business on a stretch of fifteen blocks not dominated by or directed at the Chinese population. Across the street from the bar is a market that takes up the entire block, selling, amongst other things, live bullfrogs.

The bar seats are usually occupied by older residents who moved to Sunset Park long ago from Norway, Germany, Austria, and other parts of Europe. Some of them are very old, and very fond of drink. “This is my nursing home,” said Mary. “If I get too drunk Jimmie knows how to make sure I get home.”

A large group of Chinese regulars drink bottles of Budweiser and eat one-dollar sticks of roast meat from a vendor outside in one corner of the bar, clustered around a few tables. Some of the European regulars are not entirely comfortable with them: “This neighborhood isn’t the same,” said a younger man. “My friends started leaving and those guys started coming into our country.”

“There used to be six bars on this stretch, all filled,” Jimmy, the Irish owner of the Soccer Tavern, told me. “Now this is the only one. I have only survived because of my Chinese customers. They are great. I run the only Chirish bar in all of New York.”

(Vidar)

The oldest regular, Vidar, is eighty-nine and had his first drink in the Soccer Tavern in 1943. He had left Norway on a whaling ship at the age of fifteen, just prior to the start of World War II. Unable to return because of the war, he joined the Merchant Marines, working as a gunner on cargo ships plying the North Atlantic. He survived being sunk four times. He once spent five days in a life raft. When his ships docked in Brooklyn, he and his friend would walk up the hill towards Eighth Avenue to drink in bars like the-then newish Soccer Tavern. After the war, he immigrated to Sunset Park where he found jobs on fishing boats. A hurricane in 1956 led to another rescue at sea. “That was enough,” he told me. “I moved to working on tug boats.” He retired in 1983. He recently was awarded the St. Olaf’s medal by the King for his service to Norway during the war.

Floyd Bennett Field

(Children posing with RC plane)

Floyd Bennett Field was New York’s first municipal airport. Later, it was a naval air station. Now it’s a large park used by a collection of the oddly obsessed who need large swaths of empty, flat concrete, like the radio-controlled car and truck guys, who race tiny vehicles down an old runway. In one hand, they twiddle a remote control and in another they hold a joint or a beer. They obsess over fine-tuning their little engines, revving them up to high pitches and clouds of smoke. Indifferent women stand aside, trying to keep the smaller kids from getting in the way. “If this is what makes him happy. I’m just glad he isn’t racing real cars.”

Miniature planes, each lovingly crafted, use another patch of old runway. The small planes, controlled by a group with more elaborate radio controllers, accelerate down the runway before lifting off, banking over the radio controlled cars and then over the marshes, like a tiny homage to the old airfield.

(Preparing to take off)

A small viewing stand, seemingly dragged from a little league baseball field, sits next to the runway, filled with the families of the pilots and the curious. A Hasidic man, trying desperately to keep his kids entertained, tested them on their ability to recognize the different planes: “That’s a Fokker triplane, circa 1917.” The kids ask for ice cream.

Another old runway is used to train sanitation workers to drive the massive trucks. NYC garbage trucks circle around and around, almost as if playing a slow motion, inertia-intense, game of tag. NYPD helicopters use another as a storage facility and landing pad. Scattered across the park are old massive hangers, some repurposed as sports complexes. The others sit behind fences, ever so slowly collapsing back into the ground. A husband taught his wife how to parallel park; a solitary man hit golf balls into the bay. Another man tried to teach his girlfriend how to kiss; well, that’s what it looks like, at least.

Open hydrants, all of Brooklyn

(Children in East NY street surfing)

The streets are the only summer home for much of Brooklyn. As the heat intensifies, apartments disgorge their residents and the hydrants are opened — legally, by having a spray cap installed by the fire departments, or otherwise, since on almost every block someone owns a gigantic wrench.

Mothers wash their smaller children in buckets filled from the hydrants. Others march their children out in bathing suits with soap and shampoo. Passing drivers slow down, and steer their cars slowly through the spray, turning around to clean both sides. A broken table turned upside down and bent, placed inches from the spray, shoots the water in an arc that reaches across the street and into a basketball court. A thick plastic tarp is laid across the street, slicked with water and dishwashing liquid, and turned into a giant slip and slide.

(George)

On one block, where kids have set up an old police barricade to surf on, George, who is eighty-five, came out of the broken motor home he lives in, windows clouded over with piles of junk. Originally from Honduras, he worked on freighters in the Caribbean his entire life before retiring in Brooklyn. He sat in a chair and watched the children. “I do miss being young, but I don’t mind being old, because when you get to be my age, whatever regrets you may have are hard to remember,” he told me.

As midnight approached, police in cars broke up the crowds and told the children to go home. The water ran down the street into the corner gutters that collected the afternoon’s detritus: beer cans, vodka bottles, ice cream wrappers, potato chip bags, and a few stray condoms.

Sunset at Sunset Park in Sunset Park

Sunset Park, the neighborhood, is named after Sunset Park, the park, which is a wonderful place to watch a sunset. Roughly the size of four square city blocks, the park is centered on a ridge that faces west towards the water of New York harbor. The park is pitched downwards, sloped in its lower half at an angle like a movie theater. At the top of the park, where it flattens, is a huge municipal pool, and sprinklers, and volleyball courts, and playgrounds, and basketball courts, and soccer pitches.

The neighborhood is divided roughly in two : From the water to Fifth Avenue is mostly Mexican and Central Americans; from Sixth to Twelfth Avenues is mostly Chinese. The park is a seam connecting the two very different cultures that live together because of a shared need for affordable rent. On summer afternoons, it feels as if the entire neighborhood unites in the park. Solitary boom boxes blast high-pitched music not meant for blasting: Chinese women dance ever so slowly, while Mexican families picnic to Tejano music. Women selling mangos on sticks jingle tiny bells. Children — playing soccer, or tag, or volleyball, or flying kites, or skateboarding — yelp.

Oneg Heimishe Bakery, Williamsburg

(Baker at Oneg Heimishe)

The insular Satmar Hasidic community of Williamsburg has few obvious offerings for visitors. There are wig stores for the ladies, with strict rules about the presence of men. There are Shtreimel stores for men, selling the large cylindrical fur hats that are worn on Shabbat and Jewish holidays, the ones that look like chocolate cakes. The corner stores, Satmar bodegas, sell Mayim Chaim Cola rather than Coke, as well as other kosher replacement products. Buying a Shtreimal is restricted to the Satmars; buying a Mayim Chaim Cola is not.

(Baker)

At the far end of the neighborhood’s busiest street, at 188 Lee Avenue, the Oneg Heimishe Bakery offers something that anyone would want: the city’s best chocolate bread. Made fresh each morning, it’s almost always sold out by afternoon. Early in the morning, when the bread is still hot, the chocolate inside oozes and drips. It’s served wrapped tightly in wax paper and a brown paper bag.

The Oneg Heimishe Bakery isn’t open on Saturdays or on Jewish holidays, high or low or in between, of which there are many. It isn’t open now, or any time during the summer, because the family that runs it moves upstate to Sullivan County, like many Satmars do. There are other bakeries in the neighborhood that don’t close during the summers, that have longer hours, but as their owners admit, “Oneg Heimishe has the been doing it the longest.”

At the other end of Lee Avenue, toward the water, where it runs into Division Avenue, huge towers of low-income housing, occupied by mostly Satmar families, surround small parks, like the Roberto Clemente ball field. Kids fill the park, running around playing tag. When I asked one of them, “Who is Roberto Clemente?” they shrugged.

“He was a famous baseball player,” I said.

The children asked back, in unison, without irony, “What is baseball?”

Bait and Tackle bar, Red Hook

(Looking out from Bait and Tackle at Red Hook)

Because Red Hook is severed from the rest of Brooklyn by the BQE, the difficulties of the borough during the sixties, seventies, and eighties, hit it as hard as any other neighborhood. Now, the recent upswing in Brooklyn, shifting into euphoria, has been slower to make its way to Red Hook. Rising rents haven’t yet pushed out all the working artists. Co-ops haven’t entirely replaced working industry, and the few destination restaurants, serving whatever the fuck is in vogue, still have much of the neighborhood in them.

Visitors to Red Hook, attracted by the views and the newer restaurants, or brought in by a perverse desire to make a day of IKEA, generally make their way to Sunny’s Bar, drawn by its impressive history, and by the guidebooks.

Bait and Tackle bar doesn’t get that attention, partly because it doesn’t have the history — it’s only only ten years old, not, like, a hundred. It does have everything a great bar needs: A genuine feel, cheap drinks, interesting regulars who are in fact slightly irregular, forgiving bartenders, an Irish owner, great music, enough quiet to have a real conversation, and long hours.

(Bait and Tackle during storm)

It is also very much part of the neighborhood. The night that Hurricane Sandy hit, one of the owners, Barry O’Meara, stayed in the bar as the water edged higher, trying to rescue as much as possible. “I really didn’t have a choice,” he told me. After Sandy flooded Red Hook and sent water over the top of Bait and Tackle’s bar, O’Meara and some of his regulars worked together to re-open within days. For the next few months, as crews worked on restoring power to the neighborhood, Bait and Tackle, with the help of generators, became an unofficial community center — one of the only bright spots in otherwise dim neighborhood.

Yemeni restaurants, Cobble Hill

(Waiter, Yemen Cuisine)

Atlantic Avenue, especially near its intersection with Court Street, has long been a center of Middle Eastern culture in New York City. Once primarily Syrian and Lebanese, over the last thirty years it has become equally Yemeni. An influx of a particular ethnic group is sometimes a sign of bad things back home; in Yemen, one the poorest Middle Eastern countries, a long and violent conflict between the south and north has left the economy in disarray.

Three Yemeni restaurants are clustered on the same block as a newish Trader Joe’s: Hadramout Restaurant at 172 Atlantic, Yemen Café at 176, and Yemen Cuisine around the corner at 145 Court Street.

Yemen Café, up a flight of stairs, is the oldest, and also the most comfortable for the Trader Joe’s crowd. It is well lit, well acquainted with US tastes, and fluent in English.

Hadramout, down a flight of stairs, is less so. It is harshly lit, with schoolroom-like tables littered with newspapers in Arabic. A TV in the corner, above the self-serve tea table, runs continual loops of Middle Eastern news. It serves Yemenites almost exclusively, and at times stays open until 6 am for the late night workers; other times, it stays closed for long stretches.

(Gathering at friends house)

Over the last twenty years, Yemenites have started buying many of the bodegas in Brooklyn, especially in the remaining un-gentrified neighborhoods. Many owners keep their stores open until midnight and then come to Hadramout for a meal — stews, large metal platters of meat (mostly lamb), and hot, fresh flat bread with sweet, milky tea — before going home. “We come to talk politics, business, to gossip,” Mohammed told me. “Many of us are related, we all try to help each other. Running stores. It is not very easy. It requires the whole family to work. I take my kids to Yemen every other summer. But I don’t want them to be Yemeni. I want them to be American. To be Yemeni only in spirit. To be faithful to the religion, the food, but not the craziness.”

When they leave, often after midnight, they pass two huge dumpsters on the sidewalk in front of Trader Joe’s, filled with bags and bags of food beyond its expiration date. Sometimes young Brooklynites, Freegans, climb out of the dumpsters, holding the bags.

Tatiana Restaurant, Brighton Beach

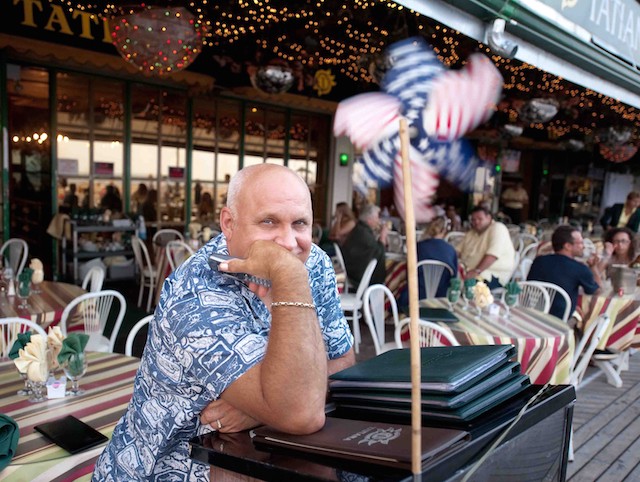

(Host, Tatiana Restaurant)

The Russian speakers who first settled in Brighton Beach — mostly Jewish refugees from Ukraine back in the nineteen fifties — couldn’t believe their luck. “Such a beautiful location, and nobody but us and the poor seemed to want to live here. The beach is better than the Black Sea, and the weather warmer than Kiev,” said Ivan.

Brighton Beach is fully formed. Newer immigrants still come; they are often from Russia and Ukraine or places close to it, like Azerbaijan or Tajikistan. Everyone speaks Russian. The usual pattern of immigration — first wave moves into neighborhood, gets wealthier, moves out, hasn’t fully played out in Brighton Beach. “I am not moving,” said Sonya, I am happy here. I have everything I could want.”

Brighton Beach is a beach town in more than just name; much of the neighborhood’s life is played out along the wooden boardwalk. When the summer brings in the rest of New York, or at least those without access to cars and second homes, the boardwalk seems to change its identity, with other languages mixed in with Russian. It reverts when the sun sets. Families come down from the apartments that hover over the boardwalk to eat and celebrate at the outdoor tables of the restaurants lining it. Of all of them, Tatiana’s is the largest and best.

Even in the fall and winter, when the visitors have left, families still gather to celebrate underneath Tatiana’s large green tent on the boardwalk. When the night turns cold, the waiters and waitresses offer guests blankets, wrapping them around their shoulders. Platters of food, all huge portions, come in waves: smoked fish, soups, and seafood. Vodka and water are consumed in almost equal measure. Between courses, smokers lean against the boardwalk railing, across from the restaurant, looking off to the ocean.

On a cool fall Sunday night in October, next to Tatiana’s, a group of students hung a white blanket on a wall. Plastic chairs were dragged out, and a Russian art movie played onto the blanket; gusts of wind distorted the movie just a bit. An older man, taking a smoking break, stopped to watch the film. One of the students offered him a hit from a joint. He waved his hand no and disappeared, only to return later with a bottle of Vodka. He handed it to the students, smiled, and went back to join his family for dinner.

Walking across the Brooklyn Bridge

(Michael, coming home)

Before Brooklyn became a brand, the Brooklyn Bridge, to most, represented Brooklyn. Tourists would walk the pedestrian walkway, along a bouncy wooden track riding between two gently arced cables, up to the apogee, stop, take pictures that have been taken a million times before, and then walk back to Manhattan, determined to get back in time to shower and dress before their Broadway show began.

The few who walked the entire length were almost always from Brooklyn: People commuting very early in the morning or late in the evening. The commuters were a small group that rarely changed, many who recognized each other from their daily walks. Another reminder that Brooklyn can be just a big small town.

There was a Chinese woman, always dressed in the same sky blue sweat suit, regardless of the weather, who walked to Brooklyn and back. She waved to everyone she passed. There was a Jamaican man who rode his modified moped, cheap radio duck-taped to dashboard, who almost hit and angered everyone he passed. There was Michael, who would walk back to his Cobble Hill home from his night of collecting cans and bottles from the just-closed bars of Manhattan. His tower of cans always seemed close to collapsing, but never did.

As Brooklyn became popular, tourists no longer stopped at the top. They went to Brooklyn for Brooklyn, not just for the view. Then the merchants came, selling sodas, selling sad NYC art, selling whatever other trinkets tourists might want. They clustered near the top, the middle of the walk, turning it into a Brooklynland spin-off of Disneyworld.

If you walk the bridge early or late enough, the tourists and merchants are gone. A few commuters are still there, walking from their homes in Brooklyn to work in Manhattan, or back the other way. At the top, during those empty hours, you can find a rarity in Brooklyn: Solitude.

Chris Arnade received his PhD in physics from Johns Hopkins University in 1992. He spent the next twenty years working as a trader on Wall Street. He left trading in 2012 to focus on photography. His “Faces of Addiction” series explores addiction in the south Bronx neighborhood in New York City.