Portrait of an Israeli Peace Protest

by Alex Cocotas

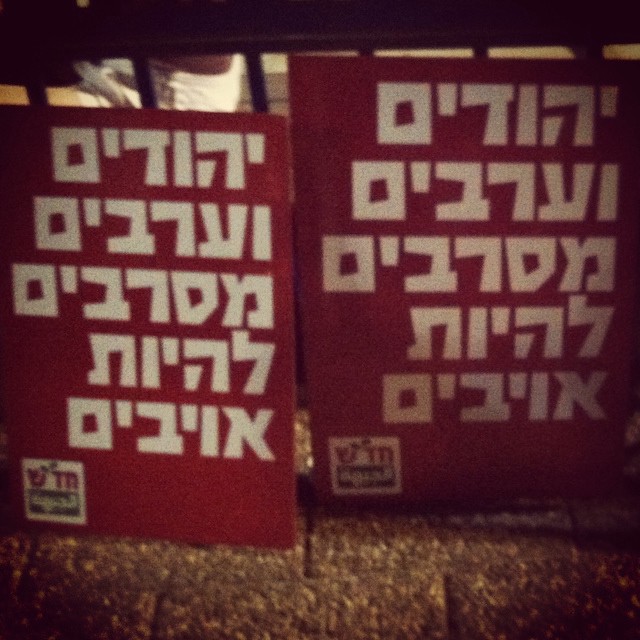

Over the past couple of weeks, a slogan has sought to bridge the gap between the Arab and Jewish communities as the conflict in Gaza has intensified: “Jews and Arabs refuse to be enemies.” As of this writing, its Facebook page has more than sixty thousand likes; participants have posted sixty-six thousand tweets and hundreds of selfies; and it has been greeted in the media with headlines like “Jewish And Arab People Are Posing Together In Inspiring Photos Saying “We Refuse To Be Enemies,” “Jews And Arabs Refuse To Be Enemies — The Powerful Pictures Pushing Peace In Gaza And Israel,” and “Jews And Arabs Refuse To Be Enemies’ Might Be The Movement That Finally Brings Peace.”

However, in the United States, where most of the tweets and pictures seem to originate, “Jews and Arabs refuse to be enemies” is stripped of its political content, context and origin in the Israeli peace movement. (The Israeli peace camp is so small, however, that it might be more accurate to say that it belongs to the Israeli left — not the mainstream Labor party, which has purposefully disassociated itself from the left, or Meretz, the largest left-wing party, which has not forcefully come out against the operation in Gaza — but tiny, Marxist-influenced, Arab-Jewish unity parties, like Hadash or the even smaller Da’am, whose activists typically form the bulk of the sparsely-attended anti-occupation protests within Israel.) In Israel, shouting “Yehudim veAravim m’sarvim l’hiyot oyavim” is not a no-stakes, feel-good slogan; it is a radical political statement that attempts to articulate a different vision for a society whose prevailing forces and voices are wrapped in a rhetoric of violence and fear, lurching from one disaster to the next — and hoping you don’t get hit in the head with a metal pole, or pepper sprayed, or followed home and attacked for doing so. Israel is a country where support for the current operation in Gaza is almost uniform (even the vacancy lights on parking garages blink out “IDF, the people are with you!” intermittently); intermarriage between Jews and Arabs is incredibly difficult as a matter of state policy; there is an active anti-miscegenation movement; peace activists have been repeatedly attacked in recent weeks by right-wing thugs chanting “death to Arabs” and “death to leftists”; and even mentioning the names of Palestinian children killed in Gaza is a “politically controversial” act worthy of censorship.

Two weeks ago, I attended the largest anti-war demonstration since the beginning of the conflict, held in Rabin Square, which plays a central role in the peace movement’s collective imagination. In 1982, four hundred thousand Israelis packed what was then known as Kings of Israel square to protest the war in Lebanon. In 1995, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, the closest thing this country has to a political saint, was assassinated by a right-wing extremist near the square after addressing a rally of a hundred thousand in support of the Oslo Accords. Every year, a memorial rally is held to commemorate his assassination, serving as sort of an annual event for the peace camp. As recently as 2006, a hundred thousand came and heard the writer David Grossman excoriate then Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, who was also on the stage. Last year, approximately thirty thousand people showed up.

Some six thousand Israelis filled Rabin Square to call for an immediate ceasefire. Even before the rally started, the atmosphere felt ominous. Two hours before it was supposed to start, the police abruptly withdrew the rally’s permit and said they would disperse any attempts to continue; the official reason was the threat of rocket fire, even though no rocket has yet landed in Tel Aviv. (The permit was reinstated after organizers said they would proceed anyway.) The demonstrators were young and old, stylish and staid, activists and average people. Some brought their children, others brought their dogs. Upon arrival at Rabin Square, they were funneled into a designated area surrounded by police barriers on the eastern side of the square — to protect them from the five hundred or so right-wing counter-demonstrators, who may or may not be organized by an aging nationalist rapper named “The Shadow.”

The demographics of who was on a given side of the barriers also bore traces of the country’s most significant intra-Jewish conflict, between Ashkenazim and Mizrahim. A significantly higher proportion of the anti-war demonstrators inside the barriers were Ashkenazim — white, European Jews. (The vast majority of American Jews are Ashkenazim.) The majority of Israeli Jews that spoke at the demonstration were Ashkenazi as well — four out of five, I believe. The counter-demonstrators outside, the right-wingers, are predominately Mizrahim, which literally translates to “easterners,” but is used as an imprecise term for Jews from the Middle East. The majority of their grandparents probably spoke Arabic as their first language; their families were deeply ingrained in Arab communities for centuries; and in culture and mannerisms, from the food they eat to the music they listen to, they are much closer to the Palestinians than their Ashkenazim counterparts. Some leftist Mizrahim self-identify as “Arab Jews,” but many Mizrahim would probably find the term pejorative.

Though there had long been an Arabic-speaking Jewish community in historic Palestine that predates Zionism, the majority of Mizrahim arrived in Israel after the establishment of the state — some by choice, others after being expelled from their home country. Upon arriving, many Mizhrai immigrants lived in transit camps, hastily built settlements and tent cities, sometimes for years. Others were bussed directly to what were euphemistically called “development towns,” wretched blocks of Soviet-style apartment blocks on the country’s periphery, sometimes on the false pretense that they were actually being taken to Jerusalem or Tel Aviv. Sderot, the city that has borne the brunt of rocket fire from Gaza, is a development town.

Ever since, Mizrahim have faced systemic discrimination from the Ashkenazi elite who controlled the military, the government, and major cultural organs — the result of their arriving first, living in the most economically desirable areas, and outright racism. David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s founding father,

famously described Mizrahi immigrants

as coming “without a trace of Jewish or human education.” The state, fearing the creeping “Levantization” of Israel, actively tried to strip them of any vestiges of Arabic culture — Mizrahi music was restricted on the radio, for example. David Ben-Gurion, again: “We do not want Israelis to become Arabs. We are in duty bound to fight against the spirit of the Levant, which corrupts individuals and societies, and preserve the authentic Jewish values as they crystallized in the Diaspora” (emphasis mine).

Even today, Mizrahim broadly lag the socioeconomic status of Ashkenazim, have fewer educational opportunities, and their communities receive less government funding. It was Benjamin Netanyahu’s party, Likud, which first cultivated the Mizrahim’s indignation into a political demographic, creating a radical shift in Israeli politics that began with “the revolution” of 1977 — which marked the first time that the right-wing took control of the government, displacing the Ashkenazi-dominated institutional left that had ruled the country since its inception. Significant remnants of those voting patterns still survive today.

The right-wing counter-demonstrators — Jews whose families would likely have been considered Arabs for centuries, now attacking other Jews for chanting “Jews and Arabs refuse to be enemies” — represent an extreme manifestation of the process by which Mizrahi identities were broken, their historic ties to Arabic culture severed and replaced with a unitary Israeli nationalism, fueled by systemic discrimination and government incitement. Today, the Israeli left and the anti-war demonstrators preaching the virtues of peace and chanting “Jews and Arabs refuse to be enemies” are perceived as the political heirs to the perpetrators of the Mizrahim’s cultural subjugation (and, more generally, an indifference to their communities), even though there are plenty of Mizrahim among them — and most of them certainly disapprove of the systematic discrimination against the Mizrahim. While there is, of course, an aspect of generalization to the split — Netanyahu is very much a member of the Ashkenazi elite, there are many Ashkenazi extremist settlers, and just because you are Ashkenazi or Mizrahi does not automatically mark you out as left or right — the division nonetheless underlies the difficulty inherent in realizing the ideals of slogans bellowed from dueling bullhorns as the anti-war demonstrators gathered in the square.

The atmosphere was more somber than other demonstrations I have attended, perhaps because of the more immediate violence, or because it had tipped past that mysterious size when its participants allow themselves to be taken more seriously. We listened to speeches. Some were moving, some were angry, some were boring. I was struck by the inability of several speakers to isolate and identify with the specific suffering of Palestinians in Gaza. The first speaker strained to acknowledge the daily stress of running to bomb shelters under rocket fire, but did not really challenge the audience to empathize with the situation of Gaza’s population, who are being bombed by one of the world’s most powerful militaries — and who don’t have bomb shelters or possibly even have homes to return to. Intermittently, you could hear the chants of counter-demonstrators breaking through the speeches like static on a country road. They chanted things like “School is out in Gaza / they have no children left there.” If you craned your neck to look at the sea of Israeli flags to the right of the stage, then behind you and to the left, you could see the fluttering blue and white looked like a nylon shark that had smelled blood and was slowly circling its prey.

The demonstration ended abruptly when a speech was cut short by a nearby police officer barking orders. We were advised to swiftly exit through the northeast corner of the square and continue north on Ibn Gevirol Street, one of Tel Aviv’s largest thoroughfares, to avoid any problems. According to Haaretz, violence from right-wing counter-protesters prompted the police to ask organizers for the demonstration to be cut short. In other words, a peaceful demonstration of six thousand was prematurely dispersed to appease the violence of five hundred. As we left, the atmosphere was charged. Small arguments and shoving matches started breaking out. I stupidly decided to stay and see what would happen, after convincing myself I could pass as a clueless American on birthright extension if I was confronted. A block north of the square on Ibn Gevriol, right-wing extremists attacked demonstrators, nearly devolving into a full-on brawl at one point, just steps from where Rabin was assassinated. Some tried to attack buses carrying demonstrators back to other cities. For a moment, it looked like it could turn into a riot as police rushed in to intervene. I saw several instances where cops protected individuals from being savagely beaten by the mob of right-wing counter-demonstrators. Despite all this, there were few arrests.

Eventually, the scene quieted down, which is to say all the anti-war demonstrators were driven away. A little while later, I walked back to the square, now mostly empty. Only the right-wing demonstrators remained, chanting and waving the Israeli flag. The police stood to the side, on the edge of the square, drinking water bottles and joking with one another. It was like nothing had happened. There was no evidence that an hour before it had been full of people, asking for peace. A sign I saw at the beginning of the demonstration was depressingly prescient, “תברחו כל עוד אפשר” — flee while you still can. As I read about the protest the next day, I noticed one report that mentioned demonstrators chanted “Jews and Arabs refuse to be enemies.” I can’t help but wonder if someone out there, a member of “Jews and Arabs refuse to be enemies,” an American perhaps, read that and thought to themselves, “Hey, we did it.”

Alex Cocotas is a writer, formerly at Business Insider, who lives in Tel Aviv.