The Legend of the Legend of Bunko Kelly, the Kidnapping King of Portland

by Elizabeth Lopatto

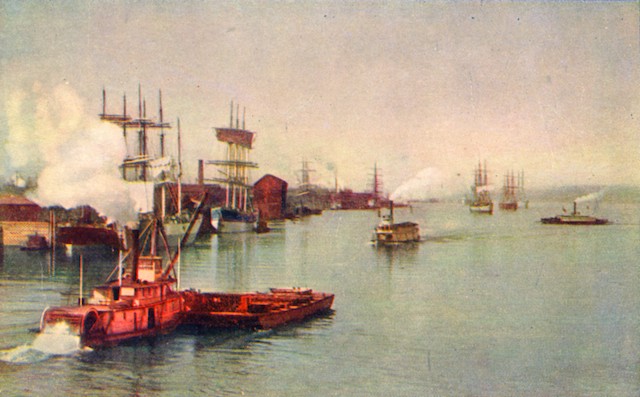

In the late eighteen hundreds, the port cities of the American West were dangerous nests of sailors, prostitutes, and gangsters — none more so than Portland, Oregon. The most infamous relic of those bad old days are not the wooly beards of its male population, but the Portland Underground, the city’s network of so-called “shanghai tunnels,” which tourists today are often told were used to spirit unsuspecting men, perhaps lured by a half-naked prostitute to an establishment where they were drugged and kidnapped, toward their final destination: pressed into service on a ship.

These kidnappers were known as crimps, and the “king of the crimps,” according to folk legend, was a man named Joseph Kelly. By his count, some two thousand souls owe their time at sea to him. Kelly spent his early life on the sea as well: In his memoir, he wrote of once being shipwrecked on the island of Madagascar. Rescued from the shipwreck by the natives, Kelly was fed soup. Afterward, he looked into the clay jug that stored the rest of the stew and discovered the right hand of one of his shipmates. When a typhoon struck, he and some other sailors followed the lead of a man described as an old pirate, and escaped from their rescuers; they were promptly picked up by pirates. Fortunately, Kelly and his band managed to lock the pirates in the ship’s belly before heading ashore in India.

In 1879, Kelly got off a ship in Portland. In those days, since sailors weren’t allowed to leave their ships until they reached their final port, many sailors disappeared when they arrived — fleeing for jobs in the local logging industry, for instance. About three-fifths of all sailors who arrived in Astoria or Portland ditched their ships. These desertions were a problem, since captains needed able-bodied men to set sail again. This gave rise to the crimps: If a ship needed to find more men, the captain sent for a crimp, who supplied bodies for up to fifty dollars a head. Kelly took up the trade and became so good at it that Stewart Holbrook, a “rough writer” who specialized in selling local Portland history to the reading public of the East Coast literary establishment, and Kelly’s somewhat besotted biographer, described him as “an artist, for the magnificent imagination he applied to his occupation was nothing short of creative.”

According to Holbrook, one October, while looking for seamen for a ship leaving the next morning, Kelley went through his usual stops on skid row — Erickson’s, Blazier’s, the Ivy Green, the Senate — and could not find a single man to press into service on a ship. Standing across the street from a cigar store, about to give up, Kelley noticed a wooden six-foot tall cedar statue Indian state outside; he wrapped the statue in tarpaulin and hauled it onto the ship’s bunk. After discovering the deception, the sailors threw the statue overboard. “Two days later,” according to Holbrook, “the Finn salmon fisherman of Astoria, a hundred-odd miles down the Columbia [River] from Portland, were astonished to drag in their nets and find a cedar Indian amid the struggling fish.” Kelly earned fifty dollars and the nickname “Bunko,” turn-of-the-century slang for a con man.

“Bunko Kelly” appeared in newspapers for the first time a few years later, according to Portland historian Barney Blalock: In April 1887, a ship’s captain wrote to the Oregonian to complain that Kelly had supplied him with a man who was rendered nearly motionless by rheumatism. By Kelly’s next mention, in 1890, a local paper described him as the “boss shanghaier in the Northwest.” But his most famous exploit was undoubtedly in 1893, when, according to Holbrook, Kelly was asked to supply the Flying Prince with twenty-two men, at a rate of thirty dollars per head. Kelly noticed an open trapdoor in a sidewalk — the kind that businesses without alleys use to take deliveries — and entered. Inside, he found twenty-four men; ten of them were dead. The group had tried to burgle the cellar of the saloon next door, but had broken into an undertaker’s shop instead; the keg they found and tapped was filled with embalming fluid. Kelly took the fourteen survivors and ten corpses to the ship, where he was paid for them all. The ship was already heading down the Columbia River when the corpses were discovered. They were removed at Astoria, Oregon, and the local papers soon caught wind of the tale, according to Holbrook.

At the time, crimping wasn’t illegal. But Kelly was eventually arrested for allegedly murdering G.W. Sayres, an opium smuggler who had been hacked to death and thrown in the Willamette River. Kelly had been fond of selling “opium” — actually clay — to the local Chinese population, according to historian J.D. Chandler, and had allegedly lured Sayres out of his home with promises of a scheme to raise about two hundred dollars by selling the fake opium, then beat him to death. Before Kelly was sentenced to life in prison, he declared his innocence and blamed the death on a frame-job by other crimps.

Kelly may have even been telling the truth. He had been working for Larry Sullivan, a prizefighter-turned-crimp; he was listed as a clerk at Sullivan’s Sailor’s Home at 113 North Second Street. By September 1894, though, Kelly had broken away from Sullivan and gone into business with someone else, renting a flophouse that was used as a boarding house on B Street. Sullivan took this poorly: Three days before the murder, Sullivan, Kelly, and two other men were taken to jail for what the local news reported was “a lively street fight.” While Kelly maintained his innocence, his story often varied: sometimes he was being framed by Sullivan; other times, he had been hired by a Portland attorney with the Pynchonian moniker of Xenophon N. Steeves, but merely to kidnap Sayres, who was pursuing a case against one of Steeves’ clients. It took a jury twelve hours to find Kelly guilty of murder in the second degree.

While in prison, Kelly wrote the memoir Thirteen Years in the Oregon State Penitentiary, in which he claims to have fought in the American Civil War (with the Southern navy, against the North), a Cuban uprising, and in Chile, where Kelly says he was part of “a regular monthly effort to overthrow the government,” working the gun turrets of a ship called Wanda that had been bought by revolutionaries.

The book didn’t sell. By the time Kelly was released in 1908, he’d been largely forgotten. He made an appearance that same year in San Francisco, when a report in the San Francisco Call stated that he worked for gang boss Abe Ruef, who was on trial for bribery: “Bunko Kelly, another undesirable, who openly reports to Ruef’s office boy, Charley Haggerty, during recesses of the court, was also present.” After a book tour in Seattle the following year, he wasn’t heard from again.

Here’s the problem with the legend of Bunko Kelly: There’s no record of either the cigar store Indian or the Flying Prince incidents. There’s no mention of a ship called The Flying Prince in the records of Lloyds of London, which insured most ships’ cargo. In fact, Kelly likely wasn’t even born in Liverpool, which is usually cited as his hometown; prison records indicate he hailed from Connecticut. The story about cannibals is so absurd that it can only be taken for a joke — after relaying it, in Thirteen Years in the Oregon State Penitentiary, Kelly says prison is worse.

Kelly does appear in the official court records — crimps often used the courts against each other — such as when, in April 1887, he took his own brother to court over a fifty-dollar debt, though he apparently remained in partnership with him. A story in the Oregonian in 1889 recounts complaints of a Samoan sailor, who said Kelly had locked him in a room when Kelly couldn’t find a ship that would readily take him. In 1891, he was arrested for keeping a “disorderly house,” according to Blalock, which could have merely meant an unlicensed saloon, but which may have also meant that he was running a whorehouse.

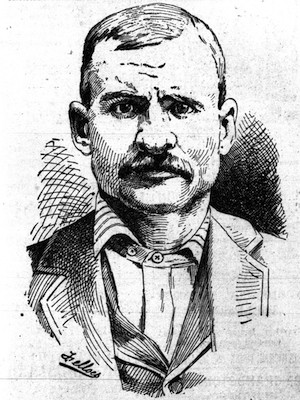

“It is my personal conviction,” Blalock writes in The Oregon Shanghaiers, “that had Bunko remained simple ‘Joe Kelly’ and not stumbled on a memorable name, had he not been convicted for a vicious murder, he would be no more likely to be remembered than any of the hundreds of bunco steerers who blew through Portland back when the city was ‘wide open.’” The real Kelly, writes Blalock in Portland’s Lost Waterfront, was “a cheap man who could make even an expensive suit look cheap. He smoked nickel cigars and slept in cheap rooms. He was a ‘blow hard’ who told ‘fish stories’ and worst of all, his word was worthless.” While Kelly is almost invariably described as being “squat” and “barrel-chested,” a sketch from his murder trial, drawn by a Portland Evening Telegram staffer, shows a man with hair loss along the temples, a heavy mustache lying across a broad, square face with a wide jaw, and a skeptical expression.

The article that made Bunko Kelly famous, published in The American Mercury, was not the first time that Stewart Holbrook had told the Flying Prince story. Sixteen years earlier, in the Oregonian, the gist of his tale was basically the same, but slightly more outrageous: Forty men are found by Kelly in the undertaker’s basement, not twenty-four. Unlike in the more famous account, however, Holbrook confesses to the reader the story may be just that: “I don’t know for certain if the story’s true, but it’s one you’ll hear from any of the old-timers.”

Prior to becoming the biographer of Bunko Kelly, Holbrook wrote a series of books about Washington, Oregon and Idaho, with a focus on the oral histories of the working class. A former lumberjack, his first job as a writer was with the Works Progress Administration in 1932, where he edited two million words on Oregon history. After that, he wrote his first book, Holy Old Mackinaw: A Natural History of the American Lumberjack; the oral histories, combined with Holbrook’s own experience with the WPA, made for a bestseller. He ultimately spent three decades at the Oregonian, making his living writing stories like that of The Flying Prince, and founded the James G. Blake Society, a jokey organization whose main goal was to prevent people from moving to Oregon.

One of Holbrook’s primary sources of the oral histories that his work relied on was Edward “Spider” Johnson, a bartender at Erickson’s Saloon, an establishment that claimed its bar was the longest in the West; Johnson’s stories were apparently too good to check. According to Blalock, “During the years he was supposed to be sparring with [Portland boxer] Jack Dempsey, hanging out with crimps and working as a sailor, records show [Johnson] working the printing presses at W.C. Noon Bag Company.” Nevertheless, Holbrook sold Johnson’s story to publishers, including the Atlantic Monthly; his piece “The Three Sirens of Portland,” published in The American Mercury in 1948, also owes its genesis to Johnson. Over time, Spider Johnson’s tales became enshrined fact in Portland mythology; some are even repeated in history books, Blalock notes.

But what about the reports of the Flying Prince? Holbrook’s account, republished in Wild Men, Wobblies and Whistle Punks by the Oregon State University Press, says specifically that the dead men “made a great rumpus in Portland,” and that Astoria newspapers “soon had the story on the wires.” If Spider Johnson’s story was true, writes historian Finn J.D. John, the newspapers of the era were oddly quiet about the incident. No reference to the Flying Prince occurs in either the Astoria or Portland papers from 1893, and no one mentions it in the coverage of the murder trial. Still, John’s remarkably optimistic about that story. “Most likely,” he writes in his book, Wicked Portland, “the story has at least some basis in fact.” It had widespread currency in the 1930s, when there were still plenty of people around who remembered the 1890s. John’s theory is that men were drugged by Kelly — who had a special concoction of knock-out drops called Kelly’s comforters — and shanghaied, though perhaps Kelly misjudged the dose on at least one occasion, and wound up with several dead would-be sailors.

The reality of the shanghaiing era in Portland was arguably even more sinister any tale about its tunnels: The crimps often didn’t use them because they didn’t need to. The most powerful crimps could kidnap someone at noon on a main street, and so long as the person wasn’t of social standing in Portland, no one cared; even someone as relatively unimportant as Bunko Kelly could operate unimpeded. Crimping was finally made illegal in the U.S. in 1915’s Seaman’s Act, but by then the practice was already dying out — the advent of steam-powered vessels meant that the need for unskilled labor on ships dropped drastically.

Today, Hobo’s Restaurant and Lounge in Portland offers tours of its “shanghai tunnels” for $13 per adult and $8 per child. You can make your reservation online.

Elizabeth Lopatto is a science writer based in Oakland. She likes philosophy of science too much for her own good. She’s on Twitter.

Images via Wicked Portland