Some Notes on the Great Fermentation

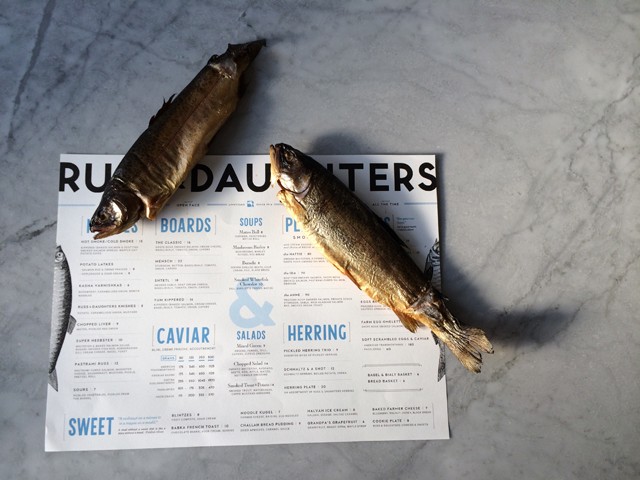

A certain kind of cooking, brought to New York City by Eastern European Jews, typified by bagels, pickled vegetables, gefilte and smoked fish, is having a genuine moment, the pinnacle of which is, perhaps, the opening of the long-awaited, full-fledged Russ & Daughters Cafe. While the Times, not incorrectly, characterizes this moment as a “sudden and strong movement among young cooks, mostly Jewish-Americans, to embrace and redeem the foods of their forebears” in order to “embrac[e] the quickly disappearing foods of their grandparents,” the trend also conveniently fits quite neatly into the current milieu of all fermented everything, which is why it probably seems so palatable to a new generation of restaurant-devouring safari hunters, Jew and Gentile alike.

From David Chang’s fermentation-powered hozon and pork bushi umami bombs to delicate, lichen-laced New Nordic food sprouting all over the place and mandatory pickle jars in restaurants to fountains of dry, almost musty cider and sour beer spilling out of tall, thin glasses, no palate worth its volcanic sea salt today is complete without a proper appreciation for funk and acidity. These deep, sharp flavors, which often manifest by way of fermentation are, obviously, deeply historical — everything was either sort of rotten or sort of pickled before refrigeration, right? — but more immediately, they’re a conceptual astringent, a palate cleanser to cut the grease of the last several years of Southern-inflected New American and offal-dense Italian, soggy and leaden with animal fat. So now we have a national obsession with Sriracha and we’ve got drinking vinegars and larb ped and artisanal kimchi and a sudden swooning over hyper-expensive sushi with its rice carefully doused in vinegar.

The full sweep of The Great Fermentation is unknown — will it be the skinny jeans of food, given that artisanal pickling already goes back a few years? — but some of its ripple effects are already promising. One of the subtexts underlining the Jewish food revival — which, at its most widely popular right now, is not about smoked herring and pickled beets, but bagels — is the dawning realization, on a mass scale, that most bagels as we now know them, even the “good ones” in New York City, are by and large sad squircles of dough:

Many a “New York bagel” today is a puffy, sweet monstrosity, made like other industrial breads; quick-risen (instead of slow-fermented), stamped out of molds (instead of hand-rolled), steamed (instead of boiled) and then misted with sugar syrups before baking to achieve an appetizing shine.

A wishful outcome, perhaps, is that Russ & Daughters will stop layering its beautiful smoked fish on some truly mediocre bagels and instead might rest it on, if not the blasphemously delicious Montreal-style bagels of Mile End’s comically overwhelmed Black Seed, then perhaps on something like “the perfect 21st-century bagel: slow-risen, water-boiled and slow-baked,” made by Melissa Weller, a former baker at Per Se and Roberta’s. And perhaps the rest of the city, even the hangover-cure bagel factories that flank every large young residential building in Manhattan, will follow its lead.