The Dead Cannot Consent

The End of the Tour is a movie currently in production based on David Lipsky’s 2010 book, Although of Course you End Up Becoming Yourself: a Road Trip with David Foster Wallace. In 1996, shortly after Wallace’s sudden burst into literary superstardom with the publication of Infinite Jest, Rolling Stone had sent Lipsky to conduct an interview with with him. The magazine spiked the interview, and years later, after Wallace’s suicide, Lipsky incorporated the material into his book — to my mind, the best about David Foster Wallace that anyone has yet written.

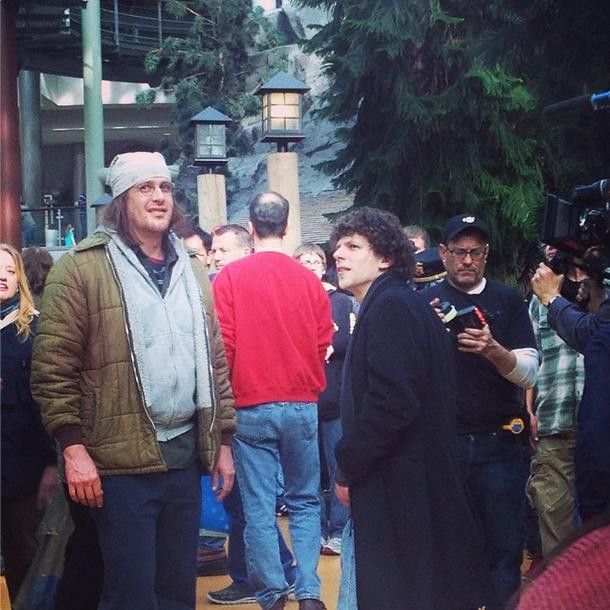

There is every reason to anticipate that the movie will be great: It stars Jason Segel as Wallace, and Jesse Eisenberg as Lipsky. (Anyone who supposes that Segel is too lightweight to play Wallace credibly, I will assume, has not seen him in the 2011 Jeff, Who Lives At Home, though Segel’s genius is equally apparent in many a deceptively goofy performance.) The director is James Ponsoldt, whose splendid The Spectacular Now contains a sensitive and idiosyncratically observant treatment of substance abuse, among many other things. I will certainly see the movie (Si Dios quiere, as my grandma used to say) and even if it is not as great as I hope, I am sure there will be a lot of pleasure to be had in seeing a favorite book come to life.

On Monday, however, the Los Angeles Times published a report under the headline, “David Foster Wallace’s Estate Comes Out Against ‘The End of the Tour’”:

The David Foster Wallace Literary Trust, David’s family, and David’s longtime publisher Little, Brown and Company wish to make it clear that they have no connection with, and neither endorse nor support “The End of the Tour.” This motion picture is loosely based on transcripts from an interview David consented to eighteen years ago for a magazine article about the publication of his novel, “Infinite Jest.” That article was never published and David would never have agreed that those saved transcripts could later be repurposed as the basis of a movie. The Trust was given no advance notice that this production was underway and, in fact, first heard of it when it was publicly announced. For the avoidance of doubt, there is no circumstance under which the David Foster Wallace Literary Trust would have consented to the adaptation of this interview into a motion picture, and we do not consider it an homage.

The question arises as to exactly why “The Trust” should have been given “advance notice that this production was underway.” Lipsky’s book was published by Crown’s Broadway Books (a division of Random House) and was based on his own experiences and recordings of personal conversations with Wallace on the eponymous road. Nobody else was in the car; Lipsky is entirely within his rights to write freely about events in his own life, including the five days he spent talking with a fellow author and recording their conversations with that author’s consent. Neither is it in any way correct to dismiss Lipsky’s book as the mere rehashing of some old unpublished interviews. The older Lipsky, the expert and much-decorated writer who produced this book, is the fulcrum upon which the whole is balanced; the book is very subtly constructed, the comment of an adult on his younger self, and on the man that younger self both admired and keenly, dispassionately observed — and not least, on all his younger self failed to see.

“For the avoidance of doubt.” Is the implication here that the public should have access only to those works that “The Trust” “considers an homage” to Wallace? Why even speculate on the sad and unfathomable question of what Wallace would or would not have consented to, had he not committed suicide? As Tom Scocca said so brutally and so incontrovertibly back in 2011, “David Foster Wallace took himself out of the conversation about what David Foster Wallace wanted, after all.” He failed himself, and surely everyone else failed him too.

Since his suicide, several works by Wallace have appeared in print, among them, This Is Water, the book version of the 2005 commencement speech he delivered at Kenyon College, published in 2009; the unfinished novel The Pale King followed in 2011; and Both Flesh And Not, a collection of previously unpublished essays, appeared in 2012. And there are more to come, including a book on tennis, and a sort of “greatest hits” collection, The David Foster Wallace Reader.

In a 2011 Times article about the publication of The Pale King, Wallace’s longtime editor Michael Pietsch (now CEO of Hachette, which owns Wallace’s publisher, Little, Brown and Company) said, “[Wallace] would never have wanted [The Pale King] to be published in an imperfect form if he had lived to finish it, but he was not alive to finish it.” He added that Wallace had left a 250-page section of the book in the center of his desk: “To me, the fact that he left those pages on his work table is proof he wanted the book published.”

Pietsch pieced The Pale King together from a mass of disconnected materials — handwritten journals and notebooks, a two-foot manuscript, stacks of computer disks, a cardboard box full of research materials — containing little clue as to Wallace’s intentions with respect to their order or disposition.

“It’s my version of the novel,” [Pietsch] admitted, adding that he talked to Little Brown’s e-book staff about creating a version that would enable the reader to arrange the chapters in any order, but was told that was technically unfeasible. Eventually all the manuscript materials will go to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, he pointed out, and “scholars will have a field day. I’m sure they’re already sharpening their teeth.”

There should be no cause for the sharpening of any teeth, it seems to me. Any honest effort to discuss, to understand, and to build on the conversation Wallace’s work began should be honored by readers in the spirit of intellectual curiosity and open-heartedness he himself embodied in his short life. The efforts of Michael Pietsch are to be admired — as are the efforts of David Lipsky, and of all involved in the forthcoming film. However troubled his personal life may have been, in the world of letters, Wallace’s candor and brotherliness taught a whole generation of readers to try, at least, to live and reason in the same way. The tragedy of Wallace’s death left an empty space where a mighty voice should have been. Nobody can take its place, and nobody should try.

Maria Bustillos is a writer and critic in Los Angeles.

Photo by Vanessa Andrade