The Internet Terror Phone

Walk down Broadway, past Canal, past banks and furniture stores, Mr. Fashion and sneaker shops and condos, old then new, brick then steel, until the buildings grow taller and begin to take up entire blocks. Turn right at the unopened Pret, across from the McDonald’s, down Thomas Street, a one-way single-lane. Look up. You can’t miss it: A monolith, brutalist, granite armored, its skeleton colossal slats of moulded concrete. It is said to feature the largest blank facade in the world. The building’s six turrets contain air ducts, a whole mess of ventilation for whatever is inside. Whatever is inside — that’s the question.

There are no windows, there are barely any signs. The only notable notice reads “no standing except authorized vehicles.” The website Above Top Secret has a thread about the building, and the sign. “The agency permitted to park there is AWM. I have never heard of an agency called AWM, and no matter how I goggle [sic] it, nothing comes up,” someone offers. Another suggests that AWM might stand for “autonomous warfare mainframe” or “atomic weapons management.” More likely, the thread concludes, AWM is the name of some unknown, secret a security contractor.

The building at 33 Thomas is full of secrets. It was built for AT&T; Long Lines, the name for the company’s long-distance network. The lines were (still are) literally long, crossing ranges and nations and laid out across the ocean floor. Where the lines converge, like they do here in lower Manhattan, there is an exchange point. The building was, perhaps still is, one such point, acting as a gigantic switchboard, where voices carried over coaxial cables moved between floors before exiting on a new line, over to New Jersey or the Atlantic Ocean and parts beyond. Each floor is supposedly 18 feet high, each square foot able to hold 250 pounds, and the walls were designed to withstand a nuclear blast.

Andrew Blum, who wrote a very good book about the internet called Tubes, said he has no idea what’s inside the building. He spent two weeks trying to get in. Whatever is in there, he said, is not the Internet, because the building is sealed off, no fiber optic tubes flow into it. At least, not from nearby. And very nearby are major hubs, one at 375 Pearl (the Verizon building) and another on 60 Hudson (the old Western Union headquarters), which are two of the most important pieces of pure Internet real estate in the northeast. No, the monolith is most likely a telco hotel, where companies rent space and house their equipment. AT&T;’s name is still decalled on the doors. The security guard at the front desk will tell you, cryptically, that it’s full of telecom stuff. Switchboards? “Yeah… switchboards.” But there is so much space. The building is 550 feet tall. What’s taking up all that space inside those granite, blast-proof walls?

Few walk down the lane but those that do are on their way somewhere, and do not stop and ponder the structure. Wait long enough and a few tourists might happen upon it, lean back, gawk, and snap a photo before moving on. One or two might comment on its ugliness, even though the building was praised, in the New York Times, in 1982, for being “the only one of the several windowless equipment buildings the phone company has built that makes any sense architecturally.” Ponder the monolith and its innards long enough, however, and you might find inspiration. This is how a trio of grad students at NYU’s ITP (Interactive Telecommunications Program) came to build a strange new kind of emergency phonebooth.

“We fell in love with the building,” said Omer Shapira, a filmmaker and journalist. “It’s just so insanely big, and dark, and what it contains no one knows. There are no blueprints online. Maybe there are NSA servers in there.” Shapira said that they first did their pondering before anyone knew who Edward Snowden was, and before cybercrime was something normal people might talk about. He and his partners, Max Ma and Ryan Bartley, wanted to find a way to link that building, full of phone lines, to its surroundings, full of Internet. “How about if we make this phone that shows the emergencies on the Internet,” Bartley said. “It would be like there’s this enormous building screaming for help.”

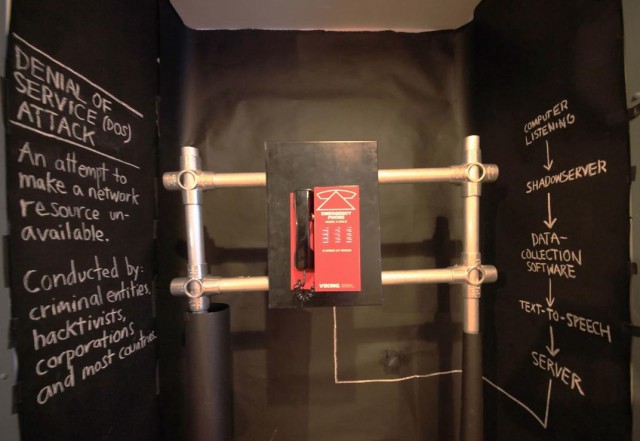

First they needed to find a way to listen in on cyberattacks. This wasn’t difficult. Shapira said that the internet is a lot like a big echo chamber — efficient routing means redundant connections. Denial-of-service (DoS) attacks reverberate between the connections. They needed a way to tap into a connection and listen for echoes. This wasn’t easy.

“Well, no one, big companies I mean, wanted to partner with us, to let us see how they were being attacked. I guess we shouldn’t have been surprised,” Shapira said. So they found databases of DoS attacks. The only problem with the databases is they weren’t in real time. Nonetheless, the range and frequency was astonishing. “The ones you hear about, from Anonymous usually, those are the most vanilla attacks, like on Scientology. You don’t hear about criminal organizations or governments, controlling millions of computers through a botnet to gain access to a server, or kill it,” Shapira said.

When he first looked at the attack logs, Bartley said: “Oh my God, this was way, way bigger than we ever thought.”

They buffered the logs by a few days, mostly so the three of them, or ITP, or NYU, wouldn’t become a target for the attackers. Then they programmed a cheap, credit-card-sized computer called a Raspberry Pi to scrape this data and spit it out. They turned the text to speech, choosing a crackly computer voice. “The feeling we want to give,” Bartley said, “is like, whenever you see a zombie movie, and the radio is replaying a message, a distress signal, that’s it.”

They housed the computer in a metal box — red, of course — and connected a telephone handset. They made it battery powered, so it could be anywhere, and talked about somehow putting it up onto or next to the building before running away. Shapira is from Israel and Ma is from China. They weren’t sure the ramifications of putting an art project phone booth on a mysterious building that might house equipment used by government spy agencies, but nothing good would come of it. They’d lose the phone, at least. Probably worse.

After asking around, they recently got permission to put the phone up somewhere outside, in public, in Williamsburg, which they plan on doing this summer. So the booth is getting weatherproofed, though it might not ever be where it’s really meant to go. Still, walk down Broadway on nearly any cold night this winter, past the cast iron storefronts on Thomas, and stare up at the monolith for a spell. The wind comes howling through the narrow lane, and if you lean back and stare up and listen enough you might just hear it: the sound of a great windowless tower, screaming with ancient emergencies.

Ryan Bradley is a writer and editor in New York.