Slow Ride Around Yangon

The man was sick, or had been for hours. When he rose, finally, it was bright out and hot, and he determined that he would not be making it to the conference that day, and instead he would ride the train that went around the city. The way he figured it was, to sit upright, indoors, and work at looking interested was more likely to bring back last night’s nausea than the train. Getting sick in front of people he knew would be embarrassing. This way, if he did puke, it’d be with strangers he would never see again. And trains calmed him.

He packed a big bottle of water and not much else before he marched, weak-kneed and slow, towards the elevator, down to the lobby, and out into the air. Outside he stopped to steady himself a moment, closed his eyes against the light and the heat. The station was close, he’d run past it just the other morning. If he could get on that train, slump down in the hard seat, stare out the window, sip on his water, he’d be fine, was what he thought. Then the man started walking again, faster this time, though his legs were still all wobbly.

At the station, trains were rusted and decaying in unused yards, on overgrown tracks that led to another station, off in the distance, this one red brick and grand once, now abandoned and collapsing in on itself. He had to ask several different officers at the current station for the commuter train ticket. Each time he did so he raised his hand, pointed his finger, and traced a circle in the air. Each time, each station officer responded “Ah,” and pointed to another booth, until one stood up and left his post, escorting the man to the office that sold tickets to the train that circumnavigated the city.

The office was small, more a concrete stand on the platform between tracks, but it had at least three fans, maybe more. It was full of breezes. A cool and pleasant enough space that two of the three men inside it were napping on cramped cots. The third stood motionless beside a stack of papers as he listened to his colleague, then looked at the man, who smiled and traced a circle in the air. Eventually a ticket was produced, signed, and paid for. During this process the man found a very small plastic chair to sit in, and he would have liked to stay this way, low to the floor in the breezy office, for as long as possible. But far too soon the third man, still standing, gestured for him to leave and wait for his train outside. Then, in nearly perfect English, he said, unprompted, “It will come in the next five minutes. It will take three hours, all the way around.”

Four minutes later the train arrived. It looked more new and clean inside than the man expected, though certainly old — no doors or windowpanes to speak of, just long hard plastic benches, the same light blue, he noticed, as the subway back home. The car wasn’t crowded. He had a section between handrails to himself. Once the train started up, he saw that all of the passengers had taken off their shoes, which were all sandals, and most had put their bare feet up on the bench. It looked very comfortable, so he did the same, though he kept his socks on, because he had socks on.

In the compartment, with the man, were five others. One was very possibly Australian, extremely tanned, her long brown hair going natty. She sat near a monk, who eyed her suspiciously before fixing his gaze at some vague middle distance outside the paneless window, thumbing his prayer beads. The other three were a handsome family. The father scraped at his face with an instrument that looked like a dull razor. The mother faced him and spoke very softly. Every so often he would nod or grunt a reply. The daughter moved to the bench across from her parents, to a gap between the windows where a shadow fell, and scrunched up into a ball and fell asleep.

Slowly, they crept around the city, going counterclockwise, past back lanes and yards and small, small plots of blocked off with tarp and plywood. The man pulled on his water bottle and leaned back, letting the low rumble and bounce of the train subdue him into a stupor.

Each stop was frequent and sudden and short, causing the car to rock back and forth along the track a little. A group of young men carrying ancient machetes, some tied to bamboo poles, swung aboard at a station called Tadalay, flinging their tools onto the floor with a clatter and laughing. The mother gave them a dirty look, the father continued scratching his face, the daughter remained in a ball, asleep. The monk didn’t flinch.

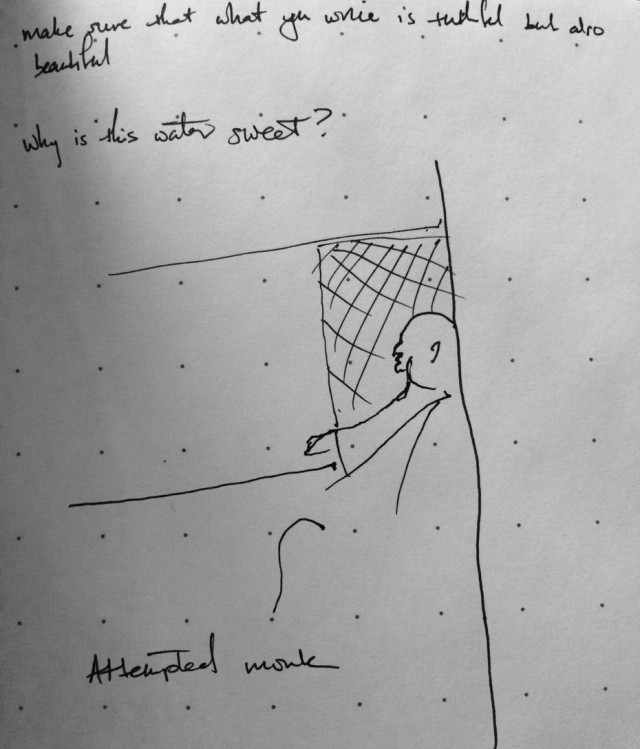

For reasons that were not clear to him the man brought out his notebook and tried to draw the monk. He could not draw very well at all, and stopped not long after he started. The folds in his robe were too tricky, and he’d screwed up the way the monk’s plump and rosy cheek turned jowly near his jawline. Instead he stared at a note he had written on the top of that page, the day before, at the conference: “Make sure that what you write is truthful but also beautiful.” The woman who said this was moderating a panel of Burmese journalists who had, at various points, been thrown in prison or out of the country for their reporting. The man pondered the note and decided he wasn’t sure about that “but.”

The train stopped, the car rocked, the man stared outside and saw a sign for Kyait Ka Lei station. The name was familiar to the man, he’d studied it on a map weeks earlier. The station was very near a newly paved and expanded highway that struck out due north and didn’t stop until it reached Mandalay. It was literally the Road to Mandalay, and very suddenly the man was overcome with a desire to see it. Days earlier, he had talked to a bus driver about the road, and the driver told him it was dangerous, they drove too fast and crashed often. The man stood up, grabbed his shoes, then grabbed the handrail and kind of fell towards the gap in the train that served as a doorway. On the platform, he put his shoes back on, then he walked to a low wall, behind which was a tree that created just enough shade to stand in. While he stood in the shade he considered that this might have been a mistake, disembarking. There was very little around on the city outskirts aside from farmland and, in the distance, a high wall and large blocks of buildings. While he was pondering what to do, a skinny dog ambled over and joined the man in his patch of shade and scratched itself.

Far across the tracks was what looked like a ticket office, a tall concrete block. He struck out towards it, shading his eyes from the light even though he had sunglasses on. Once there, he saw it was in fact a ticket office and that it was closed, and he felt a momentary panic followed by a wave of overwhelming lightness. The man laughed. He would be at this quiet platform in the suburbs of Yangon for a few hours at the longest, before another train arrived, and that was the worst that could happen, and that wasn’t so bad. He had a bottle of water to sip on, he had some shade. Just then, on the other side of the ticket office, a taxi arrived and two men, what looked like a father and son, got out.

The man ran over to the taxi. The driver looked extremely surprised, and even more surprised when the man asked to go see the road to Mandalay. The father and son stood off to the side, watching. “Mandalay?” the driver said. “Mandalay,” the man said. “No, no, no, no, no. Two days. Too far,” the driver said. “Oh no. Only the highway. Only to see,” then the man made a gesture with his fingers and his eyes that was supposed to mean “to see.” The driver’s surprised look turned into something more like fear or panic, and the man worried suddenly that the driver might pull away, so he got into the backseat. “Just down the road,” the man said. “Not far.” He took out his phone and pulled up Google Maps and zoomed in on where they now were, pointing to the station, which was a tiny blue icon, and the highway, which was a thick yellow line. The driver stared at the phone a long time, then took out his phone, which was, like the man’s, also a computer, and pulled up a program that wasn’t Google Maps but had a map of the area, too, and pointed to a thick line that the man thought must also be the road to Mandalay, so the man nodded vigorously, and they were off.

Not two minutes later the taxi pulled onto the road to Mandalay, which was two lanes separated by a wide patch of red dirt, cutting through patchy farmland and then, just over an incline, patchy jungle. There were few cars, mostly large trucks, and three buses packed with passengers. After eight minutes going north the man said, “OK, let’s go back,” but they did not stop. Then the man yelled “OK” and the driver turned around and the car swerved and the man grabbed onto where a seatbelt should be, to buckle himself, and realized there wasn’t one. “OK! Let’s turn around!” said the man, and pointed to the other two lanes of highway across the patch of red dirt, the lanes that went south. The driver slowed the car in the middle of the highway and the man panicked a little as a truck blew past, then the driver eased the car across the dirt and onto the southern lanes, and ten minutes later they were back at the station. The man paid the driver the equivalent of $3, and the driver smiled while still looking confused, and the man smiled, imaging the driver telling his friends about the crazy foreigner who wanted to see the road to Mandalay and drive on it for less than 20 minutes.

The man walked back to the patch of shade, where the dog was now asleep, and took another pull from his water bottle and slumped down against the wall and waited and pulled out his notebook and wrote very little, then thought about how he wished he thought more deeply in the moment, or at least moments like these, where not much was happening. The dog’s tail began thumping, throwing up a cloud of dust, and the man worried he might come over for a pat. He liked dogs but wasn’t sure about this one yet. Ten, twenty, thirty, maybe even 40 minutes passed before another train pulled up and he boarded it. The dog had barely moved in that time. It was nearly empty, the train, and the few passengers on the far side of the car were huddled in spots between paneless windows where the shadows fell. The man did the same, but before long the train had completed its long arch north of the city and was heading south, back towards the central station. The the shadows fell differently, were more pronounced, so the man could spread out again and drift off, which he did.

Many stops later the train pulled up to a station called Phawt Kan, and a little man with a big, bright plastic bag full of foliage got onboard. He had a neon pink sash around his torso and a thick, pink bandanna coiled around his head, and resting on top of that a wide straw hat, held in place by shoestring tied under the little man’s chin. He put his bag down and stared out the door for a time, then carefully took off his hat and placed it on the bench and sat down next to it, took off his sandals, and brought his feet up under him. The little man grabbed the bag and pulled it over to where it was in front of him, then began rummaging through the leaves and branches, pulling out a few and laying them down next to him, opposite the hat.

The little man then uncoiled the pink bandanna from around his head and spread it across the leaves. He took the sash from around his torso and put it behind his head, ready to tie it, but then stayed like that for half a minute, just kind of leaning back, resting his head against the cloth, while holding the cloth with both hands. It was weird, was what the man thought, watching this. The little man grinned and put the sash down, on top of the bandanna, and took out more foliage and laid it on top of the sash. Leaning down, rummaging through the bag, he produced a ball, possibly for soccer, faded and coming apart. He put it in his lap and smiled. The train slowed to a stop and rocked.

The little man stood up and put the ball down, resting his foot on top of it, holding it there in place for a moment, then flipped the ball up on top of his foot, balancing it, and kicked up once, then twice, then it got away from him and rolled down the car and out the door and onto the platform. The train started back up. The little man ran out the door after it, yelling, then ran back to the door, after the train. He hopped back on board, without his ball, and sat down again next to his pink fabrics and branches and leaves. The little man sighed. The man sighed too. It was a bummer, to lose that ball.

The man stared out the window again, and the lanes became cluttered again, the city regaining its density as they neared its center. He saw thousands and thousands of small plastic wrappers piled up among the roots of banyan trees and clogging a small muddy creek. The train passed a school, and through the bars on its windows he saw dozens of small children smiling shyly. A few waved at the man, and he waved back. He saw a small Hindu temple, where someone was sleeping, out of the sun. Then he saw the backside of large buildings, and the back of a huge market where they sold fabrics and rubies and jade. Then he saw the old station, falling in on itself in places. Then the train was back where he began and so he got off. Back on the platform he saw a sign on the ticket office he hadn’t notice before. It read:

He liked that, and took a picture, and walked back to his hotel.

Ryan Bradley is a writer and editor in New York.