Riding That Train, High On Terrain

by Dan Packel

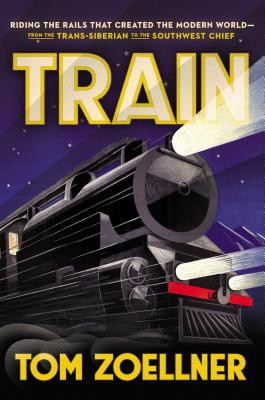

With the writers abuzz with talk of securing Amtrak Residencies, Tom Zoellner’s concisely titled Train comes at a good time. The Los Angeles writer rode the rails in six different countries on three continents to research his new book. He also traveled from New York to Los Angeles on our often-embattled national carrier.

Amtrak appears to have recently scored a rare PR win, after managing to turn an offhand remark from Awl-pal Alexander Chee into an as-yet-unnamed but perhaps-soon-to-be-formalized program aimed at giving writers free or low-cost rides. Writer Jessica Gross has already done such a rolling residency; Chee will take to the rails in May.

I called up Zoellner to ask him what he thought of the idea, and how trains lend themselves to such whimsy while owing their origins to hard material realities of conquest and profit.

Tom Zoellner’s Train is available wherever books are sold, which is to say, not aboard trains.

• Amazon

• B&N;

Do you write on trains?

It’s such fun. It’s such sort of a sensory experience. You got the physical movement of the cars, you’ve got the rhythmic clickety clack. You’ve got the hushed conversations of people talking around you. There’s the smeared images, scrolling by outside the window. The whole thing really puts you into a state of reverie. I can think of no better environment, particularly in the United States, to think sort of philosophical thoughts.

Are you surprised that this idea has managed to strike such a nerve?

No, the only thing surprising is that nobody thought of it sooner. The train is our most poetic form of conveyance, and Amtrak for years has had a public relations deficit, in terms of people really appreciating what they have to offer. Amtrak is unfortunately too often the punch line to a joke, instead of us recognizing that it keeps the spirit of American railroads alive.

Do you think they’re actually going to be able to institutionalize it?

I sure hope so. Just as a parenthetical, I myself am going to not apply — I think I’m kind of ethically disqualified. I’ve written about Amtrak, number one. Number two, I’m probably going to continue to write about them in some form and I don’t want to take free stuff from them.

To me it seems that the idea is really motivated by a romanticism, which you touch upon in the book. But it seems that the bigger theme, which you touch upon in almost every chapter, is this idea that railroads perpetuate some form or other of exploitation. Did you have that theme when you began exploring the project or did you pick it up as you went along?

I had a sense that railroads were not exactly — let’s focus this just on America for the time being — they weren’t exactly great corporate citizens, particularly in the 19th century. I knew the history, but I didn’t really appreciate the depth of it: the manipulation of state legislatures, the utterly callous attitude they had to the lives of their employees, the economic predatory stance that they took, particularly in unsettled Western states. The record on railroads encompasses a whole range of organizational behavior. By that I mean that they were responsible for doing great good, but a lot of lives were destroyed in the process.

In so many of your national chapters you recognize railroads, justly, as agents of colonialism, essentially.

Yeah. There’s no better way to move heavy goods from place to place. If you’re going to have a coal mine — and this is true from the very beginning in Great Britain — you need a railroad, to really move the commodities at a huge rate, at an empire-building rate. If you’re trying to exploit agricultural or mineral riches, in spite of a remote place, a railroad is an indispensable tool. I remember a fairly vivid image from a guy named Eduardo Galeano, who wrote an important book called the Open Veins of Latin America, in which he compared the sugar-hauling railroads of Brazil to “the fingers of an open hand.” His point, that he makes over and over again, is the way that an international commodities economy in some of these nations prevented these nations from growing an internal market. In other words, there was a really insidious form of dependence. And certainly, in many parts of the American West, what developed were Third World extractive economies, rather than small-scale sustainable economies.

One of the places where the human costs of railroading continues to be really apparent is in India, where I’ve spend a decent amount of time living. I’ve probably ridden more trains in India than anywhere else. The figure that always sticks in my mind is in Mumbai, where 3,000 people die in ways connected to the local train system every year. You talk about the lack of safety culture in India. Was it surprising to you when you first uncovered it?

I didn’t know what to expect. I knew almost nothing about Indian railways, other than that it was extensive. The human costs of running the rails, and the extreme proximity of many of the neighborhoods in India to the tracks — that was a surprise. The crowded carriages, the ticketless travel. India is a challenge to the senses for many travelers — particular urban India — with all its myriad sights and smells, with things coming at you all the time, and railroads were of a piece with that. It’s such a contradiction, it’s a serene form of travel, and a number of aspects that are very jarring.

Do you see any way to get past the institutional impediments that stand in the way of a functioning safety culture?

That is going to require a couple of things. First of all, capital investment to bring actual 21st century signaling technology into the network. That costs a lot of money, and that’s not money that India really has to spare right now. There are so many other infrastructure items on their agenda, and I don’t see that coming for a while.

The other thing is that so much of Indian railways, the operational side is handled by human labor and really in different countries would be automated, just because it’s a tremendous job provisions fund. It employs an astonishing number of people, and to fire those people would be inhumane in its own way, if you know what I mean. It would mean denying the wages that support not just a person but an entire family, an entire extended family, so there’s a compassion aspect, strangely enough, to keep Indian railways staffing at its current levels.

Speaking of Indian railways, when I first read Paul Theroux I was on an Indian train. There’s certainly echoes of his book The Great Railway Bazaar in yours, although you’re doing somewhat different things — you’re certainly doing more than a travelogue here. For one, I was happy, but surprised, to see that in post-Soviet Russia, they still make the distinction between Hard Class versus Soft Class.

It is a huge difference in quality, let me tell you.

You read Theroux’s book and then your book and you realize that there’s something about train travel that lends itself to snap judgments of other people. When you’re depicting people on your travels, do you need to be mindful of not coming across as a jerk?

I want to say that I have tremendous admiration for Paul Theroux. He’s got a unique prose style. He pioneered the area of a train journey itself as a way to engage the people of a county in really fresh and unexpected ways. Theroux, famously, is sort of ill-tempered. I’ve never met him, but in person I understand for real he’s actually a very nice guy. Really cordial, really gentlemanly. But, in his prose, he comes across as a dick — a real judgmental sort that says snotty things about people. It can be fun to read but it also lends itself to, as you say, making surface distinctions, and on a train, where, you’ve got — by definition — a limited time with someone, these are instant friendships. You get to talking about strange things, very unexpectedly. You hear a lot of life stories that you wouldn’t otherwise hear, and you never know when it’s going to end — when the person is going to get off. It is a scenario that is ripe for, perhaps, simplifying a person’s story.

Fair enough.

I tried mightily not to do that.

From your opening anecdote — being on the train deep in Pennsylvania somewhere and encountering a woman who is sobbing quietly — it made me think back to a friend of mine, who told a story one time: he was on a train from Chicago to New York, and he took psychedelic mushrooms and he was very convinced that there was also a woman on the train who was tripping at the same time. I’m wondering if you ever took psychedelic drugs on a train and whether it’s an experience that you would care to repeat.

[Laughter] The answer is no. I did drink scotch on trains, which is not as exciting. I did sit next to people who were most probably high, on weed. But as far as the walls dripping and the cookie monster appearing, no.

Dan Packel is a reporter in Philadelphia who writes primarily about food and travel. He can also be found on Twitter.