On Lena, On Rihanna, On Kimye: The Very Necessary Death Of "Vogue"

by Haley Mlotek

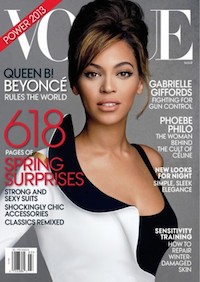

The idea that there is an appropriate subject for a Vogue cover is a concept that Vogue invented. The years and years of white, able-bodied, skinny and young models and actresses have trained us to instinctively notice what is and isn’t Vogue. There is the occasional diversion if the Academy Awards/Grammys/culture demands; but often when Vogue puts aside its insistence that only one kind of beauty exists in order to recognize a different kind of beauty, they do something worse, like the LeBron James cover with Gisele, which was maybe not an overtly racist decision, but certainly an editorial decision that reflected implicitly racist beliefs about the way a black man looks with a white-looking woman. Even (Vogue cover star) Beyoncé fired shots at Vogue on her latest (perfect) album, talking about their impossible standards of beauty on “Pretty Hurts” (“Vogue says/thinner is better,” she sings, and the first time I heard that I got REAL CHILLS).

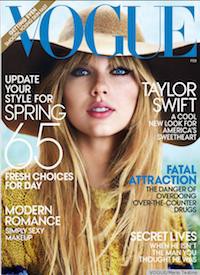

Vogue wants us to believe that their publication is merely a reflection of cultural values, and not one of the most powerful shaping tools for those cultural values. When they insist on yet another Blake Lively or Gwyneth Paltrow cover, they are, they silently protest, just giving the people what they want — whether they like it or not. I feel confident in asserting that no one was pounding down Vogue’s door for a Blake Lively cover — and it certainly turned out that no one was desperate for a Taylor Swift cover either — but rather that Vogue wanted its readers to want Blake Lively, the way they’d like them to want the Clarins family, or Lauren Santo Domingo, or a similar blonde socialite born into money and status, because it is good for Vogue’s business if they are pushing something that can literally never be obtained by 98% of their readers. It’s aspirational, is the argument, but really it is the opposite. The Vogue mentality is a crushing, totalitarian, all-encompassing binary of right and wrong, and good bad, and no one can ever really obtain it. The best case scenario is to get rich and die buying.

I work for a fashion magazine. Because I work in fashion, that means that I am constantly in the process of explaining myself, defending myself, trying to prove that I belong at certain breakfasts and lunches and talks and panel discussions. And because we are a “small” publication, we have to explain ourselves as well — and I hate defining my publication by negations. We’re “not” a lot of things, of course: not stupid, not trying to sell you something, not focusing on chasing trends, and, most of all, we’re Not Vogue. This is a question so frequently asked I would add it to the frequently asked question section of our site if it would not feel like a dagger through our sensitive well-dressed hearts. We’ve been asked, on multiple occasions, if we are like Vogue, if we hate Vogue, if our publication is the anti-Vogue, which are ludicrous questions.

But the question has had its desired effect on us, and for the last few years, we’ve kind of adopted it as an informal slogan; when we do something ridiculous, like handwrite and mail every single one of our subscriptions, or fill our fridge with water bottles and Diet Coke, or delay a meeting because the associate editors haven’t returned from our local discount grocery store (No Frills) with our favorite off-brand potato chips (World Of Flavours Poutine Flavour Rippled Potato Chips, what’s up, Galen Weston Jr.), we’ll say to each other, “Just like at Vogue!” Because, as we are supposed to understand, no one at Vogue would ever sully her hands with an actual envelope; no one would grime her manicure with a potato chip; fine, they may love bottled water and aspartame-based soft drinks, but that’s where the similarities end.

We’re not really talking about Vogue, the magazine. We mean Vogue the idea. Vogue the magazine is really a front for Vogue the institution, a facade that allows casual readers and people breezing by in grocery stores to understand what Vogue means. Which is: that wealth is good and necessary, a cleansing tool that keeps your wardrobes, cars, and homes fresh and current; that trends are the creation of single thoughtful humans, the result of pure effort by lone genius artists; that the pursuit of thinness is worthwhile and not some gauche game but a pleasant activity that above all benefits your health and mind; and that finally, the people that you, the reader, want to see are already in their pages, because no one in or on Vogue does not deserve to be there.

And yet, I don’t hate Vogue. I actually love Vogue, and buy it every month, because it satisfies a need I have for a certain kind of mainstream fashion publication — even as it provokes me to a dark rage about its deeper failings.

In all its twists and turns since 1892, Vogue has published some of the greatest writers of our time, with some of the greatest works of their careers, and when people write off Vogue I have to assume they are probably misogynistic idiots. For every article on which $125 bottle of sunscreen you simply must take to St. Barth’s this winter, there’s Joan Didion publishing “On Self-Respect” (June, 1961). To say that Vogue is all fluff, and destructive fluff, is just a lie — it would be like saying that Vanity Fair is not an exceptionally well-bred tabloid.

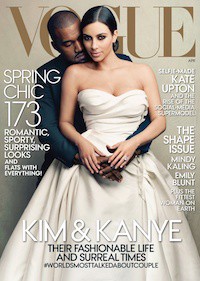

So I have a baby here and I have some bathwater and I only want to get rid of one of them. And really that thing is the idea that fashion writing is inherently stupid, and that real fashion writers must transcend this stupidity in order to write about what really matters, or that all fashion magazines must be destroyed before they infect the real (or at least, men’s) publications. (Way too late, by the way; check the April Details cover profile of Nikolaj Coster-Waldau for the ultimate in fluff, running alongside photos of him shirtless in sweatpants — Diesel sweatpants. Or this trailer for the new Esquire.) The people who believe this are the people on my news and Twitter feeds who are currently performing similar, but opposite, rants about what I think is the most glorious magazine cover of 2014 and possibly my life, Kanye West and Kim Kardashian on Vogue, hashtag the most talked about couple in the world. These people — amongst them Nikki Finke, Sarah Michelle Gellar, and fashion blogger BryanBoy because, sure, why not — are upset that Vogue has stooped so low, are indulging the masses, playing to the lowest common denominator, and then some of them are upset that people even care one way or the other about a Kim Kardashian and Kanye West cover, and they are all wrong in such a deep and disturbing way that I would happily throw a baby out a window just to get rid of their bathwater.

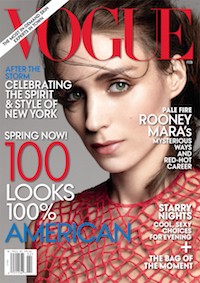

February, March, April 2012

February, March, April 2013

February, March, April 2014

For the last year or so, there’s been a rumor that Anna Wintour has enforced an “over my dead body” policy about featuring Kim Kardashian on the cover of Vogue. Now, in her April issue editor’s letter, Wintour talks about how much she always wanted Kim in Vogue, and so I’ll take her at her word — it’s probably not as simple as Anna Wintour just didn’t want Kim, and it’s even more likely it’s a complete lie. Whether or not Anna Wintour really was deliberately trying to keep Kim out of Vogue is mostly irrelevant — it’s one of those tabloid lies that speaks to a truth that people feel about Kim, that she doesn’t deserve what is a totally meaningless and arbitrary status symbol like a Vogue cover, because she or what she stands for is somehow unworthy.

I rather feel like a Kimye apologist, because I have actually kept up more with Vogue than I ever have with the Kardashians; I primarily know Kim through her social media accounts, and through the GIFs popping up on Tumblr now and then, so I’ve just decided to like her. She seems really funny, and fun, and I think she knows exactly what she’s doing at all times, and that often the arguments I hear people make about her are tied up in their overall feelings about women — that she’s stupid, or trashy, or whatever word they prefer meaning “too sexually available” — all subtext for a grown woman who does whatever she wants, who likes her body, who spends lots of time and energy looking a certain way and is happy with what she sees in the mirror. These are crimes against humanity according to the people who would like Vogue to retain their, I don’t know, journalistic integrity or whatever. And I love Kanye West beyond all reason, which has a lot to do with the fact that The College Dropout came out when I was in high school and so is burned into my brain as the soundtrack of my teenage years, but I do really think he’s one of the smartest and most talented people working in music today, and that everything he says is genius. “Everything is exactly the same,” he told Seth Meyers, and he was so right I could have tattooed that statement on my body right then and there. Everything is the same — fashion and music and art and writing and all modes of creativity we want to use to express ourselves, they are all just mediums, and Kanye West is just not interested in forcing himself into narrow categories because it makes you feel more comfortable about what a singer or rapper or musician should be.

There is little that Kim Kardashian and Kanye West could do or say, at this point, that would make me feel anything bad towards them, and there is very little that Vogue can do to convince me that it is not the enforcer of those narrow categories that all humans are supposed to fit in or GTFO. So now I am in a precarious position. Do I support Vogue for making this choice, and hesitantly make my peace with the publication, keeping my rage to a discrete eyeroll every now and then, or do I choose to see this as opportunistic — a bone thrown to bitches like myself with an opinion on just about everything?

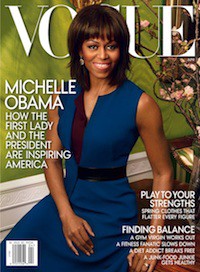

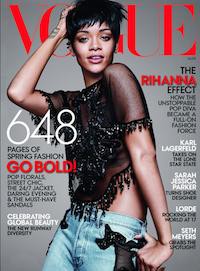

This cover comes as a what-the-what trilogy: Lena Dunham, Rihanna, and now Kanye and Kim, hashtag the world’s most talked about couple, a three-month stretch of people who are actually very zeitgeist-y (Dunham) and very popular (Rihanna — in her third cover appearance since 2011) and mostly very young — for young readers as well as young themselves. (For reference, the February, March and April Vogue covers ten years ago were Natalie Portman, Angelina Jolie and Gwen Stefani.) The Lena Dunham cover is in no way as important to me as the Kanye and Kim cover, but it was definitely the first thing about Vogue that has made me sit up and take notice in a long time. The Lena Dunham cover was, I thought, financially risky — I do like Lena Dunham and “Girls” quite a bit, in case you care about my opinion, which of course you don’t — but in purely practical terms, she is not exactly famous enough to warrant a Vogue cover. The season three premiere of “Girls” had 1.1 million viewers, an all-time high for the show and basically the amount of dollars Rihanna makes every time she posts a photo on Instagram. At the time, I raged at the Lena Dunham cover not because I hate Lena Dunham, but because in pure practical financial and cynical publishing terms, Kim Kardashian is guaranteed to move more units of any magazine than Lena Dunham is — even if Kardashian sales are apparently down for Us Weekly, they were reportedly only down to 400,000 copies per issue, newsstand numbers I can only have tear-soaked dreams about. Vogue too, actually: their single-copy sales were down 20% in 2013, down to a number well south of Us Weekly’s. There’s a reason that Vogue is taking chances.

Jezebel, as they will, asked for unretouched photos of the Lena Dunham photo shoot because they believed that Vogue would do what Vogue does often and unapologetically — flatten a human being into a 2D object of their own making, force someone to fit inside those narrow categories. It was fair for Jezebel to assume that Vogue would Photoshop Lena Dunham into oblivion, although I do believe it was tacky and mean to offer a bounty for those images; but this is what I mean when I talk about doing Vogue’s work for them. Vogue did not really retouch those images any more so than was appropriate — Dunham looked like a more Annie Leibovitz-version of herself, which is a mostly pleasant experience that I think any of us should insist upon, should we be featured in Vogue (lol). When Jezebel offered cash to prove that Lena Dunham IRL would not look like Lena Dunham in Vogue, they were reinforcing the Vogue ideal of beauty that even Vogue had disregarded for this particular photo shoot — because Lena Dunham has always shown her naked body, Vogue could not really deviate far from the reality of how Dunham looks. We would’ve had a weekly reminder that Vogue was fucking around with her image. This is what real power, and real privilege looks like. I wish Jezebel had focused less on priding themselves on knowing what a Vogue woman should look like and instead realize that we were watching Vogue completely renegotiate their place in a post-”Girls” (I’m so sorry) world. Lena Dunham has an HBO show for a lot of reasons — both talent and perseverance, for starters — but she is also in a unique position, a beloved battleground for thinkpieces and essays, particularly among the young. Vogue actually couldn’t airbrush the reality of her body away, and that’s real power. Not even Oprah fucking Winfrey got that level of respect — Anna Wintour famously asked her to lose weight before her 1998 cover. Let’s take a moment and think about that. Oprah fucking Winfrey, one of the rare women who has more wealth, power, and fame than Anna Wintour (particularly at this time, which was both pre-The Devil Wears Prada and pre-September Issue image reboot for Wintour), allowed a Condé Nast publication to tell her what sort of body she needed to have before she could be considered Vogue material. Jezebel wasn’t wrong to assume that Vogue would do something similar to Lena Dunham, but they were wrong to underestimate how much Vogue was willing to concede for a certain type of privileged person.

Then came the Rihanna cover, with an accompanying feature by Plum Sykes that made me cringe in a very adolescent way — it’s one of those stunt profiles, where Plum Sykes and Rihanna go to the Alexander Wang store for a makeover montage, so Sykes can become more like (read: dress more like) Rihanna, and the whole experience had the distinct feeling that my parents were embarrassing me in front of my coolest friend. This is ridiculous, given how involved Rihanna is with fashion. But it was there: a cover that reflected not just a trend, but a pop star of epic, untouchable proportions, a woman of limitless talent and wealth and power in an absurdly difficult industry. The writing, the Plum Sykes-ing, was just the internal mechanisms of old Vogue not catching up to the new Vogue.

Because it’s that Vogue tone that many people respond to negatively, I think, without even consciously realizing they’re rebelling against it. It’s the tone used to encourage fur-lined Birkenstocks and pajama pant suits with total seriousness and reduces First Ladies and Secretaries of States to Oscar de la Renta mannequins. I’m exaggerating, but only mildly. Really, it’s that tone that encourages you to see all fashion and all clothing as good or bad, right or wrong, worthy or garbage, and it’s a tone that’s easy to rebel against. That tone is responsible for the unbelievably misplaced backlash against last month’s normcore article by Fiona Duncan, an essay that was an absolutely perfect piece of fashion writing, which anyone who read past the title and who wasn’t permanently trapped in a snark-feedback loop would have realized. Fiona’s article was exploring an emerging trend, who was wearing it and why, their inspirations and their motivations, and the trend’s place in this fashion wheel we’re all on whether we like it or not. I think people are so used to the kind of tone that Vogue has propagated and benefited from, the tone that says all clothing is just another capitalist trap to keep the masses down, that they expected the article to be “ten chinos for your summer normcore look” or some similar shit and reacted accordingly.

Great fashion writing doesn’t reduce everything to what is for sale, what’s hot and not. Great fashion writing looks at clothing and the uses of clothing with the same amount of cultural reverence we give a Lars von Trier movie or the U.S. Open, as something that exists, and it asks why it exists, and how it fits into its larger culture. Vogue can do this when they want, and can do it well, but it is often buried between hundreds of pages of Plum Sykes talking about how standing next to Rihanna makes her feel (“Rihanna looks brilliant, and so original, ‘Rhianna,’ I tell her, ‘I feel drab, frumpy. I feel mommy-ish and totally uncool in every fashion way possible.’ The intensity of these feelings increases with every second I spend with Rihanna.” Sadly, this story does not end with Rihanna confirming that yes, Plum Sykes is majorly basic, and then Rihanna gets into a hovercar with Drake and flies away, like my latest fan fiction. Instead Rihanna just gives her a leather jacket to try on). So let me say that no one cares how normcore makes you feel, if you would wear it or not wear it; it exists, and it matters, because the way we wear and use clothing always matters, as Kanye West knows better than anyone else; everything is exactly the same, indeed, and that there are ways we can look at clothing that do not have Vogue’s fingerprints on them.

But with all this combined — Jezebel insisting that Lena Dunham couldn’t possibly be up to Vogue’s impossible standards of beauty, comments and tweets deriding the integrity of a Vogue cover now that #Kimye has graced it, backlash against the mere implication that clothing is a perfect tool for looking at a community and contemporary mindset and can be more than just something to be bought and traded for cultural capital — it leaves us doing the devil’s work of enforcing Vogue standards while Anna Wintour gets to write editor’s letters defending her humanitarian choice to give the people what they want and put Kanye and Kim on the cover. Vogue does not just exist in a tasteful vacuum; every page is carefully and painstakingly designed to be bought and sold by you, the reader, as Vogue, and when we choose to take to our own Twitter and Facebook profiles and comment sections to say that Kim Kardashian is just “not Vogue” we are doing their dirtiest work for them. We get to practice actual Vogue actions, like trying to stifle and smother and humiliate any human who deviates from the “right” kind of Vogue cover model. Meanwhile, Anna Wintour gets to float away on a money cloud to the very top of Condé Nast’s chain — the number three slot in the company’s power structure, listed well above the company’s actual editorial director.

What I hope is that the Kimye cover is the first sign that Vogue has decided to renegotiate their place in what is the graveyard we call print media. (But not at Condé, not yet: Vogue had its second-biggest issue in its entire history last September.) Vogue will always be Vogue, but Vogue does not have to be Vogue, do you follow? The last three covers are right, the sign of a new Vogue. These last three covers show that the publication as a whole may have actually been wrong all along. This is a sign of Vogue’s own way of adapting, and changing, and recognizing that the model they’ve created for themselves is unsustainable and often grossly narrow-minded. I cannot be Vogue, you cannot be Vogue, and now Vogue can no longer keep up with Vogue’s standards — not if they want to keep their preferred spot at the front of newsstands. That is a good, positive thing, to acknowledge that no one can be just like Vogue. Vogue is dead, and Vogue should die, so long live Vogue.

Haley Mlotek has a lot of opinions. She is the publisher of WORN Fashion Journal.