Zoo Stories

by Casey N. Cep

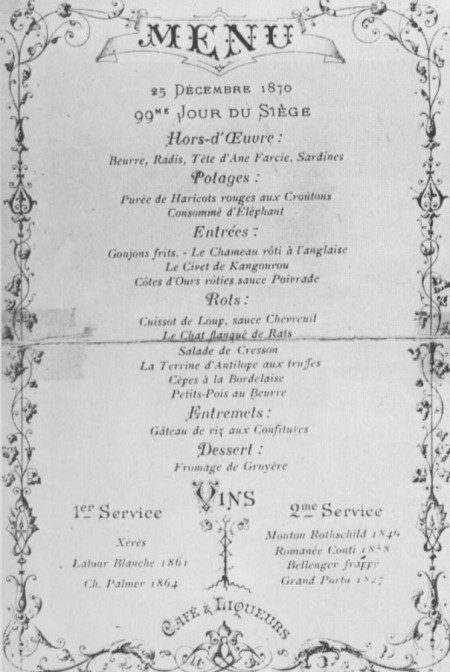

After they dined on Napoleon’s horses, the Parisians ate all the feral cats and stray dogs they could find. It was 1870, and the real politicking of Otto von Bismarck had brought Prussian forces to France. The siege of Paris began on September 19th, and over the next four months the Parisians would eat every horse, donkey, dog, cat and rat within the city’s walls. When they ran out of those, they turned to the city’s zoo, in the Jardin de Plantes.

The deer and antelope were the first to go, looking comfortably like the horses and donkeys that had filled menus during the first few weeks of the siege. The zebras, camels, and kangaroos followed. Quite reasonably, the hippopotamus was deemed by butchers to be too expensive, the big cats too dangerous for their likely meager meat, and the monkeys too anthropomorphic for anyone to be comfortable killing them. This was, after all, the age of Darwin, and monkeys seemed more and more like family.

Steel bullets took out the elephants, a pair of brothers much beloved who died one day after another on December 29th and 30th, as if the new year could not be welcomed without some kind of special sacrifice. Less than a month later, the siege ended, but not before Castor and Pollux, as the elephants were called, elicited lukewarm reports from diners: “Yesterday, I had a slice of Pollux for dinner,” wrote London’s Daily News columnist Henry Du Pré Labouchère, collected in his Diary of the Besieged Resident of Paris: “It was tough, coarse, and oily, and I do not recommend English families to eat elephant as long as they can get beef or mutton.”

I thought of the Jardin de Plantes the other day when it seemed that all the world was fixated on another tragedy in a different zoo. An eighteen-month-old giraffe named Marius was killed and fed to a different species of siege victims: the lions at the Copenhagen Zoo. This was no attack on zoo property or accidental overdose by zoo staff. Deemed genetically redundant by the European Breeding Programme for Giraffes and the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, Marius was anesthetized, then shot in the head with a bolt-action pistol.

Children and other visitors watched the killing and the necropsy, gawking for three hours as white-coated technicians dissected and disassembled the giraffe’s body. Damnatio ad bestias: Marius was fed to the lions, his spotted fur still visible despite dismemberment. The bolt-action gun was chosen so that no chemicals would affect the big cats who consumed his carcass.

Zoo stories are their own genre of tragedy. Gus the polar bear euthanized at the Central Park Zoo after being treated with Prozac for depression. Eighteen Bengal tigers, 17 lions, six black bears, three mountain lions, two grizzly bears, a baboon, and a wolf all shot and killed after being released from their cages in Zanesville, Ohio. Knut the polar bear drowned at the Berlin Zoo after many characterized him as stressed by captivity. Six lions, including four cubs, killed the same weekend as Marius — the Longleat Safari Park in Wiltshire, England, claimed they had grown aggressive and needed to be culled for the safety of the herd.

Make yourself an inventory of every zoo you have ever visited. Remember every petting zoo at every state fair you ever attended and every national zoo in every country you’ve visited around the world. Now add to your inventory every zoo that you have ever watched on television or through a live stream. The inventory grows and grows: many Americans will have seen far many and more creatures in captivity than they have ever seen in the wild.

What is wild? It is hard to remember, even harder to determine when animals are in nearly as much danger there as in captivity. A few thousand species go extinct every year as sea levels rise, forests are depleted, droughts evaporate watering holes, wetlands are drained, and construction, logging, and mining convert wild places for human use. Two-thirds of the world’s forest elephants were killed in the last dozen years. The wild doesn’t seem any safer than the zoos of Berlin, Copenhagen, New York, or Zanesville.

Costa Rica announced last summer that it is closing all of its zoos. The four hundred animals who called those zoos home will not be set loose on the street, but relocated to private rescue centers and, when possible, rehabilitated in order to be returned to the wild. “We are getting rid of the cages and reinforcing the idea of interacting with biodiversity in botanical parks in a natural way,” said René Castro, Costa Rica’s Environment Minister. If you made that inventory of every zoo you have ever visited than you might, like me, struggle to remember the way of nature.

There haven’t always been zoos; they are a human invention to delight and entertain, then more recently to educate and promote conservation. There was a first zoo, and we may hope that sometime soon there will be a last. The argument for zoos is that the imperial menagerie has evolved into a vital center of conservation where species on the brink are restored through selective breeding and careful reintroduction into the wild. But that rarely happens: California condors and black-footed ferrets, yes, but the successes of conservation are few and far between, and rarely undertaken by zoos.

Marius was neither threatened nor endangered. He was bred only to be deemed genetically redundant, brought into the world only to be butchered. His killing was defended as necessary to prevent inbreeding and also as an important act of education for the very children that came to see animals alive, not dead — much less put to death before their eyes. What happened to Marius makes the idea that our interactions with animals might return to “natural” seem impossible, yet imperative.

Years ago I stopped eating animals, and I believe now that I am done gaping at them, too. Whatever standing I thought I had above the savagery of the Siege of Paris, I see now that it is a farce; all of our zoo stories are full of such savagery, whether we devour animals with our stomachs or only our eyes.

Animals suffer in zoos whether or not we put bolt-action pistols to their heads, and no story we tell can ever be worth such suffering. Our stories of education and conservation are often just that: fiction to excuse our baser motives for looking at animals in cages. Surely whatever educative value we thought could come only from gawking at caged animals is now surpassed by watching films of the same animals in the wild.

Deracination is always a tragedy, but our zoos work ever harder to disguise it. Instead of hoping for more realistic enclosures or better-engineered exhibits of the environment, we should cease our simulations.

Marius was not killed because the Copenhagen Zoo refused contraception, castration, or the transfer offers of zoos in England, the Netherlands, and Sweden. It was not some failure of zoo policies. It was very existence of zoos that led to the giraffe’s killing. They are living cemeteries.

Some of this sentiment was already stirring in the millions who watched Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s documentary Blackfish. To see SeaWorld’s prized orca Tilikum captured off the coast of Iceland only to devolve into madness as he was made to perform endlessly and breed frequently convinced many that the costs of captivity were too high. The film encouraged boycotts and protests of SeaWorld specifically, but also a consideration of zoological parks more generally.

Animals held captive in zoos are rarely satisfactory research surrogates for their wild peers. Much of the research conducted by zoos focuses on improving the experience of captivity. Zoos research how to make better zoos. Breeding programs are being freshly scrutinized as observers realize how many animals are brought into the world to generate headlines and increase attendance in the first few weeks of their lives, only to be deemed redundant shortly thereafter. The killing of Marius last weekend and the announcement by another Danish zoo that they might well have to kill another giraffe — also named Marius — in the coming weeks has left many wondering what value there can be in spending millions of dollars to breed animals who are killed because they cannot be released into the wild and are not wanted by the very zoos that bred them.

My own zoo inventory is filled with sadness: animals hidden in their cages, or visible in their enclosures but motionless and morose; children who raged because the simulations of nature were not as entertaining as what they’d seen on television, rattling at cages and tapping on glass because they wanted the animals to look alive or do something; adults who assured one another and their children that the animals were not sad but happy, that captivity was not some kind of punishment or prison, despite the evidence before them: the torpor of the lion, the desperate eyes of the fat zebra, the birds pulling their feathers, the endless panic of the sardine ball at the aquarium. I hope that soon there are no zoos left to visit. Costa Rica is the first, but will not be the last country to close its zoos.

There is so much human suffering in the world that it may seem a distraction, perhaps even an affectation, to consider the suffering of animals. Few are now, or perhaps ever will be, willing to stop eating animals. But surely enough of us are ready to acknowledge that zoos are experiments in unnecessary cruelty; instead of improvement or reform, we must fight for abolition. The killing of Marius should not galvanize to reform zoos but to abolish them. We are enabling tragedies more horrifying than when the Parisians feasted on their captive animals.

Casey N. Cep is a writer from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. You can lodge complaints or follow her on Twitter: @cncep. Photo from the Detroit zoo by Scott Calleja.