Phone Home, Astrodome: Inside America's Brave And Crumbling Stadiums

by Anthony Paletta

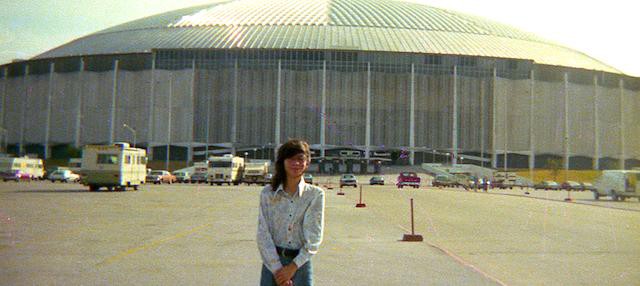

Sheer size is generally a strong guarantee of commercial longevity in American society. Consider Sport Utility Vehicles throughout almost every variation in gas prices. Consider the Big Gulp. But when it comes to some of our largest feats of construction — sporting facilities — immense size won’t usually even guarantee a lifespan as long as the most immemorable ranch home. How old is your house or residence? And how many people live there? The Houston Astrodome has a capacity of 67,925,and is 49 years old. It may not last to see 50.

Tastes are fickle, extortionate team demands are common, and the drive for novelty is endless, but the sheer inability of the greatest leviathans on the landscape to last more than a few decades seems a situation out of the great age of whaling. Of course, nature always builds a majestic whale; humans generally design mediocre stadiums. The misfortune though is that the great reaper has claimed nearly every variety of sporting architecture, with the rare great designs falling as surely as the many dull ones. The Astrodome was added this month to the National Register of Historic Places; despite this, Houston seems likely to be up one parking lot and down one historic place in the very near future.

The Astrodome was the world’s first domed and air-conditioned stadium, hailed as an architectural marvel upon its construction. In just about every promotion for the Astrodome it was dubbed an “Eighth Wonder of the World”; so have about 40 other items on Wikipedia, but wherever it might land on any world list it was a wonder for Houston, a feat of design whose form amply justified its name’s nod to the technical striving of Houston’s NASA Johnson Space Center. Christopher Hawthorne, the architecture critic of the Los Angeles Times, opened a piece on the dome: “Forget Monticello or the Chrysler building: There may be no piece of architecture more quintessentially American than the Astrodome.”

Designed by Hermon Lloyd & W.B. Morgan, and Wilson, Morris, Crain and Anderson, the Astrodome stands 18 stories high and covers 9 and a half acres. The dome was no accident — Houston was only granted a baseball team on the condition that it build a covered stadium, rendering the harsh Houston climate suitable for the baseball season. Early reconfigurations to the grass gave the world Astroturf. It served as a model for countless other domed stadiums around the world, most of which aren’t as interesting, but that’s life.

The Astrodome played host to the namesake Astros, the Houston Oilers, Robert Altman’s Brewster McCloud, the 1992 Republican National convention, and about every musical tour of anyone you might expect. It is the only sporting facility named in a Neil Young song. It is also in imminent peril of destruction. The Oilers decamped to Tennessee in 1996. The Astros moved across town in 1999. The Texans play in Reliant Stadium across a sea of parking lots. The dome remained host to events until 2009, but has been unused since (Brewster McCloud would be delighted, and perhaps Bud Cort is). It sits vacant, subject to increasing cries for its demolition. Frequently stadiums are leveled in pursuit of the understandable goal of restoring urban street fabrics; there never was such a thing in Houston, and the Astrodome’s surroundings consist only of more and more parking. Here, detractors are simply looking to forestall maintenance costs. A $217 million bond issue to redevelop the stadium into a convention and exhibition center was rejected by voters by 53% in November. In the absence of some plan for reuse the stadium seems unlikely to last for long.

This is a familiar story for American sporting facilities. Unless you’re in that venerable first-rank of pre-war ballparks, occupied by Fenway Park (1912) and Wrigley Field (1914) no one seems to care much. There may be something preservative in nature about the midwest, as the NFC North holds the two oldest stadiums in the NFL: Lambeau Field, which opened in 1957, and Soldier Field, the only football facility of any age, opened in 1924. The third-oldest NFL facility, Candlestick Park, saw its last 49ers game in December, and the Orange County Coliseum, the fourth oldest football stadium (also the fifth oldest baseball field), and last remaining multiuse football and baseball field, seems perpetually under threat. And in fairness, when it comes to the latter two cases, who really cares?

It’s difficult to mourn the passing of the 1960s and 70s legacy of multiuse stadiums. They tended to be ugly, utilitarian, hostile to pedestrians, and often perched on urban sites leveled of any genuine life. It’s rare that any technical obsolescence prompted their replacement; team owner brinksmanship often produced this condition. With the exception of that uncouth Oakland Coliseum (now the O.co Coliseum), when it comes to football and baseball, American stadiums are now as fastidiously segregated as the breakfast nook and formal dining room of some modernist house. Whether these were necessary or not, and regardless of how long you’ll be paying the municipal bonds necessary for their construction, new facilities of the 1990s and 2000s are generally, if dull, at least something of a step up — generally. Caught up in a fervor of new construction, American cities, like Houston thus far, have proven blithely unwilling to consider the rare cases of architecturally distinguished sporting facilities, or instances in which conversion might have offered some new use for facilities that simply don’t boast sufficient luxury boxes for any standard of contemporary avarice.

Busch stadium, mid-demolition, 2005, by Tyson Blanquart

The original Busch stadium in St. Louis, mainly the work of the firm of Sverdrup and Parcel, featured a modernist-monumental “crown of arches” by Edward Durell Stone (architect of the Kennedy Center and the United States Embassy in New Delhi, among much else). It made a colonnade of 96 arches featuring columns of a slenderness both technically unthinkable in any classical age of architecture and of a frank historicism aesthetically unthinkable to most doctrinaire modernists. Stone was given to all varieties of lattices and screens in his work, and these usually offered only teasing glimpses of the structures beneath. Here the arches furnished considerable transparency, and an undulating texture of runways as a pleasantly destabilizing contrast to their own lines. Gone now, it goes without saying.

The New Haven Coliseum demolition, 2007, by Staxringold.

Kevin Roche’s startling New Haven Coliseum was another intriguing facility lost and in this case not even replaced. Roche (best known for an assortment of office works from the Ford Foundation Building to the Union Carbide Headquarters) inverted any traditional order of automobile-age arrangements by placing a parking slab on top of the facility. (Frank Lloyd Wright once designed a planetarium with parking hugging the exterior but Roche actually succeeded in getting his design built.) Vincent Scully dubbed the design “paramilitary dandyism” and while hardly cozy, it offered a blunt and striking geometry of form; a column and block supporting a parking deck, offset by a sedilla-like spiral of automobile ramps. a half-mile’s irritant to motorists but intriguing to anyone else. Or, more likely, only a few persons. Was the Coliseum also an example of some of the worst excesses of 1960s design? Sure, yet it sat on a site connected to any meaningful grid only on one side; a highway and rail lines ensure that its redevelopment won’t offer much of a connection to anywhere. Plans for the reuse of the location are only now gathering some steam, after the site’s sat vacant, used as parking since its 2007 demolition. Proposals for the removal of the highway are also afoot, but unfunded, and even if the road’s removed its neighbors on the south aren’t anything you’d want to walk through. As is often the case, a parade of “if onlys” replaces actually unique architecture.

A rather intrinsically easier case (and one with far more celebrity friends), the Miami Marine Stadium, placed on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Most Endangered List in 2009, still languishes. A stadium constructed for powerboat racing by unsung Cuban emigre architect Hilario Candela, it’s sat unused since Hurricane Andrew, a haven for graffiti and wildlife and the occasional photoshoot. Its rippling cantilevered roof resembles a pterodactyl set on its side, its concrete tendons a rejoinder to any idea that substance is only suited to deployment in blocks. Gloria Estefan and Jimmy Buffett hosted a January fundraiser in support of a drive to restore the facility (if you’re interested in the setlist here it is, no one will record your name for checking it). That’s not the strangest pairing the facility’s witnessed; Sammy Davis Junior hugged Richard Nixon here in 1972 — but then again they were old pals. The facility still has a way to go to viability and reuse.

The Miami Marine Stadium in 2012.

A Miami waterfront stadium naturally has a somewhat easier time of it than other endangered facilities, but a persistent lack of imagination has characterized attitudes towards older stadiums. There are a handful of examples of successful reuse. A 1931 minor league baseball field in Indianapolis, Bush Stadium, has been converted to lofts. The “postmodern Egyptian Revival” (you won’t see that term used often) Pyramid Arena in Memphis (operational for only a shocking 14 years) is being converted into a Bass Pro Shops store (hey, whatever gets the job done). There is local inspiration in Houston for some reuse; the Summit, the former home of the Houston Rockets, is now Joel Osteen’s megachurch. But the Astrodome, in fairness, is far larger than any of these conversions, and accordingly a much greater challenge for reuse. There’s no question that the dome would prove a considerable expense in any case; the question really is whether that soaring space is something that the community is comfortable with simply throwing away.

A rather plainspokenly droll recent Houston Chronicle editorial advocated routine maintenance if just for the sake of the Astrodome serving as “the world’s largest lawn ornament.” Given that American sporting facilities get put down as blithely as racehorses when they’re no longer functional, life as a lawn ornament, breadbox or pocketwatch would be just fine. There are plenty of parking lots; there’s only one Astrodome.

Previously: There Are Now Just 357 American Drive-In Theaters

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn. He has written for The Wall Street Journal, Metropolis, The Daily Beast, Bookforum, and The Millions on urban policy, historic preservation, cinema, literature, and board wargaming. Astrodome interior by Brandon Martin-Anderson. Astrodome exterior from 1975 by Craig Howell.