On "Dawson," on "Dexter," on "Damages": The Artists and Art of TV Shows

by Johannah King-Slutzky

A couple months ago I was watching an episode of the second season of “Dawson’s Creek” when I saw an intriguing painting, “Winter’s Mist,” by an artist called “Jarvis.” “Winter’s Mist” looked vaguely familiar and the artist’s name was something I might’ve heard in college. Here is what the on-TV college lecturer had to say about it:

I’d like to close with this piece, “Winter Mist.” It’s Jarvis’ most famous work. No one can deny after looking at this exquisitely tuned surface, the juxtaposition of color and shape, the intensity of his lines, that Jarvis was in complete control of his new technique. Sadly, three weeks after Jarvis completed “Winter Mist,” he died from alcohol poisoning. Despite his untimely death, Jarvis left a lasting impression on the art world and his title of one of the abstract expressionists of the 20th century will live on.

The painting is a revelation for the show’s stars, Joey and Jack, who are high school auditors. For Joey, it’s her first exposure to serious art and launches her on an (eventually aborted) character arc in which she pursues her true passion, figure drawing. For Jack, it is the beginning of a creeping admission that he might be a little too cultured for heterosexuality. (This was 1998.)

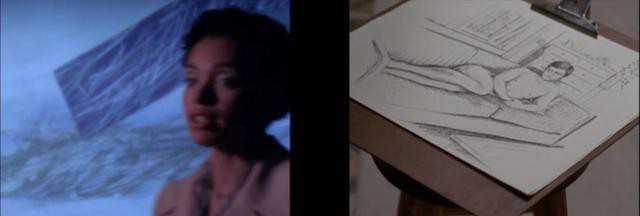

Art as sexual revelation makes a second appearance later in the season when Joey draws a Titanically nude Jack, after which the pair a) almost get it on, thereby severing Joey’s relationship with Dawson, and b) confirming that Jack does not enjoy sex with women.

Screencaps from “Dawson’s Creek.” Left: “Winter’s Mist,” by Jarvis. Right: sketch of Jack McPhee, by Joey Potter.

It turns out there is an abstract expressionist named Jarvis — Donald Jarvis — but he died in 2001, three years after that “Dawson’s Creek” episode aired and proclaimed Jarvis long dead. Definitely not the same Jarvis. But I was intrigued that a piece of fake art had been given provenance, auteur mythology, and emotional resonance. What was at stake here?

Since I found “Winter’s Mist,” I’ve been keeping a log of all the fine art I see on television, which you can find at artontv.tumblr.com. My favorite is the really bad art you see on shows like “Law & Order: SVU,” “Revenge,” and my current art favorite, “Bones.” Almost as a rule, crime pays off in bad taste. I have also yet to encounter a TV program that does not feature at least one artist or work of art, much in the same way that sitcoms tend to oversample brick lofts.

No narrative purpose. Much respect.

I spoke with the art historian David Raskin for some insight into some of TV’s mediocre and very bad art. Raskin, whose most recent book is on minimalist artist Donald Judd, specializes in modern and contemporary art history. According to his faculty profile at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, he’s particularly interested in the question “What makes art credible?”

For Raskin, TV art is almost always too palatable. “Performance art is not about someone splashing paint on walls. It’s about belief and necessity, about an artist risking him- or herself in public,” he said. “There’s no risk here, just a mess to clean up.”

As an example, here is one of my bad art favorites: from “SVU,” an example of performance art that supposedly comes to us by way of the Saatchi Gallery.

Stills from “Law & Order: SVU.” According to the gallery owner, “talent like hers is very rare.”

Then there’s TV art that you can’t distinguish from real art at all. For example, I had to take to social media to confirm that this painting, from “Damages,” was not secretly a Pollock or (in Raskin’s more likely comparison) a Frankenthaler.

Screencap from “Damages.”

Most TV art straddles the ridiculous and the familiar. Because of this, TV art’s paratexts signal inauthenticity while the painting, sculpture, or performance themselves remain unremarkable. For example, on “Bones” the fictional artist Geoffrey Thorne crushes cars into tofu-like blocks, films the machinery, and stages the finished slabs as sculpture. It’s a stunt Raskin dismissively calls “big metal.” But the concept and process is not unreasonable — or unfamiliar. John Chamberlain began endlessly crushing cars in 1959, and, the same year this episode of “Bones” premiered, the German artist Dirk Skreber was crushing cars for art, too.

Screencap from “Bones.”

TV art is headed in the right direction, but it’s been flattened. The failure of these fabricated art objects to be neither valid nor completely ridiculous means that most of the comedy comes from outside the art. In the same “Bones” episode, the gallery owner is a dragon lady white woman in Geisha costume. She says things like, “Goeffrey’s work is a brilliant examination of consumerism and the destruction of the soul” while commanding the FBI not to stomp on her pig’s-blood-covered floor.

Good narrative must show, not tell, but without an organization like the Public Art Fund or HBO’s coffers, you can only finance so much. I suspect this, and not anti-art sentiment, is why TV’s artists and critics are such windbags: their task is to reveal what the art cannot. In this system, the badness of art and artist is tautological. TV shows buy generic prop art because they couldn’t possibly get the good stuff; then, the burden of exegesis falls onto the artist. But because his or her work is plainly boring, script writers have to make the artist into a self-important lunatic in order to caulk the cognitive dissonance. This only amplifies the boring art/windbag artist trope for future TV shows.

One way to escape this mythology is to make the art worse and less legitimate. That’s what happens on sitcoms like “Friends.” Other shows deflate artists through intelligent criticism. On “Damages,” Patty Hewes’s prodigal son is an artist who knows he’s borrowing legitimacy conferred by his gallerina girlfriend. “de Kooning supported himself as a house painter when he first came to America,” says his girlfriend, Jill. “I don’t think you’re looking at the next de Kooning,” he replies.

Screencap of extremely bad art from “Friends.”

Then again, sometimes we really do just need to poke fun at art. On “Six Feet Under,” which could afford to and did feature the work of real artists, Claire Fisher accurately explains the ideology of gigantism when confronted with a huge lollipop sculpture. Then another character points out that the artwork’s oversexed creator has built yet another shrine to his penis.

How does art actually get on TV? There’s the stuff that comes from prop shops, like “Winter’s Mist.” When you factor in decorative art, this is the vast majority of art on TV.

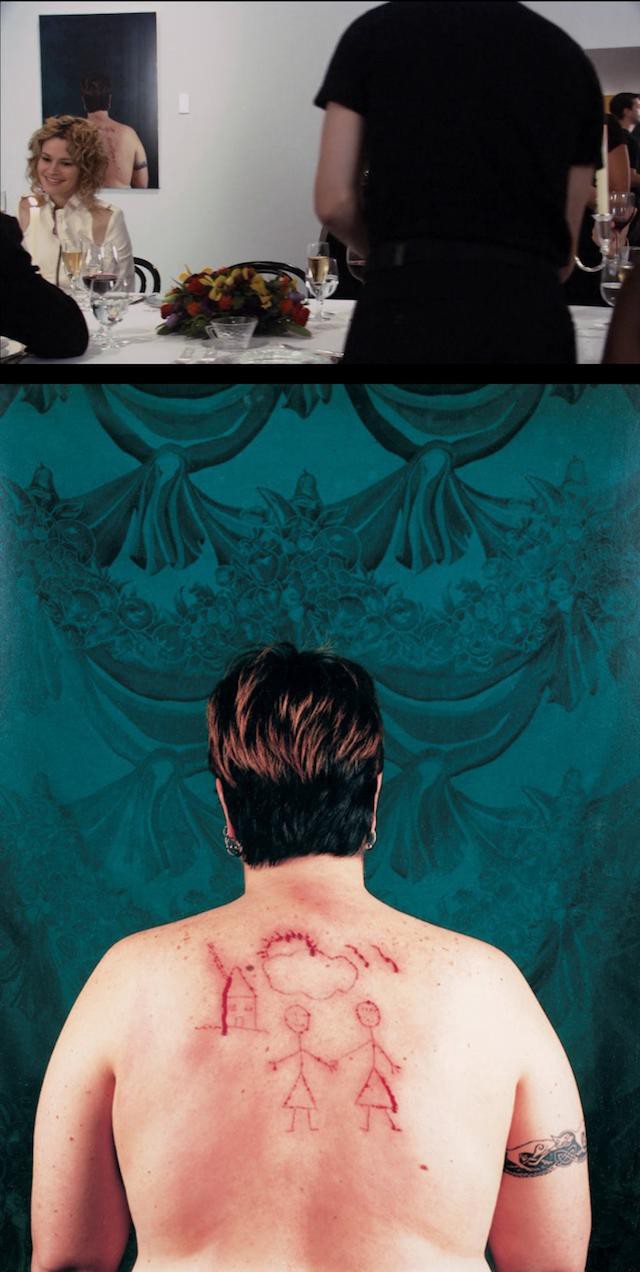

Then there’s real art by real artists which simply happens to be spotlighted on television. “The L Word” makes good use of art by featuring artists like Catherine Opie both in the diegesis and the credits.

Top: Screencap from “The L Word.” Bottom: Catherine Opie’s “Self-Portrait/Cutting” (1993).

There’s also art which has been commissioned from real artists expressly for appearance on television. “Gossip Girl” does this with very impressive artists, thanks to the show’s alliance with the Art Production Fund. IRL artist Jessica Craig-Martin’s glossy close-ups of skirts and poolside legs are perfectly matched for “Gossip Girl.”

Jessica Craig-Martin’s “Showing Pink” was commissioned by “Gossip Girl” for appearance in the van der Woodsen home.

On “Six Feet Under,” Claire’s scary mask portraits of her family were done by David Meanix, who “hounded” the show’s art director for two years. And, late in the show, the disturbing wedding portraits “shot” by Claire were taken by Lara Porzak, whose clients include everyone from James Van Der Beek to Brad Pitt (with a stop-off at Ellen DeGeneres’s wedding).

While TV shows like “Gossip Girl” and “The L Word” feature great art from real artists in almost every episode, shows like “Girls” exhibit art by their production teams.

Booth Jonathan’s unnamed video box was made for “Girls” by production designer Matt Munn.

But for art that is not commissioned or not made in-house, the most opaque part of the process of getting art on TV is not where production crews get their art, but how art ends up in prop shops in the first place. For this, I emailed artist Lisa Gizara, a photographer and painter whose work has appeared on shows as diverse as “House,” “CSI: Las Vegas,” “Californication,” “Castle,” “Whitney,” “Modern Family,” and most notably, as Roger Sterling’s office decor on “Mad Men.” You will also be able to see her work in the upcoming Terrence Malick film Knight of Cups.

Left: Still from “Mad Men.” Right: Lisa Gizara’s “Queen of Hearts.” Both images courtesy of the artist.

According to Gizara, artists shouldn’t expect to be contacted by art directors or prop shops out of the blue:

Initially a friend introduced me to the art director for the pilot for “Californication.” He asked to see some of my work and requested that I put together a number of images of New York City. He chose a piece of mine that ended up on the set on the fireplace mantle in Hank Moody’s apartment. It was an infrared photograph of Washington Square Park in NYC and you can see it on the pilot.

After that I approached an art sales and rental gallery that caters to the film and television industry. There are several in Los Angeles. I mentioned that I had my work on “Californication” and the curator of the space asked that I email a small selection of my artwork and photos. Then the curator asked that I bring in a number of framed images for the showroom — that was in 2007. I have been working with them now for 7 years and continually see my work on commercials, TV shows and feature films.

Most of the art you see on TV has been rented. At Lost and Found, a Chelsea-NYC prop shop with a larger than average collection of art, you can rent, say, framed embroidery of a horse for $75 per week or “Vintage Gold Tangle Sculpture” for $65 per week. Neither is for sale. Even innocuous artwork can be very popular. When I called for a price quote on Tangle Sculpture, it had already been rented out.

Vintage Gold Tangle Sculpture from Lost and Found.

Prop shops also have a separate category of art called “Cleared Art,” which is artwork whose rights are owned outright by the prop shop, meaning that there is no risk of copyright infringement for shows who wish to use recognizable or distinctive artwork. Cleared or otherwise, none of the paintings or sculptures I encountered at any prop shop publically displayed artist’s information. Artwork is identified primarily by a prop-shop assigned serial number, physical dimensions, and generic title (“Gold Tangle,” “Organic Painting”). Although Gizara always receives a paystub for her rented art, she’s not always informed which show actually intends to feature her painting or photo. “It takes some sleuthing on my part,” she said.

What can these props actually teach us about our conception of art? For one thing, we’re wary of abstract expressionism. If TV is to be believed, Ab Ex is pretentious, illegible — and the artist almost always has ulterior motives. If you plan to keep an eye out for art on TV, get familiar with this shot:

Screencap from “Parenthood”

Screencap from “Damages”

Screencap from “Gossip Girl”

Screencap from “The Wire”

Screencap from “Mad Men”

Standard dialogue goes something along the lines of “Ruh??” For example, from “Damages”:

DAVE: I prefer paintings I understand. Foxes, hounds, bugles, that kind of thing. All this abstraction looks the same to me.

WALTER: Well, in this case, Dave, you’re right. This piece of shit is a waste of canvas.

Art might be more opaque, more pretentious, more cutting-edge, but it will not get this treatment unless it’s abstract.

Another preconception: only jerks make video art. I’ve seen a lot of murderers and adulterers look at Ab Ex, but video artists are just obnoxious. Performance, installation, and conceptual art also rank high on the jerk-o-meter. This expectation is entirely explicit. On “Gossip Girl,” the season two love interest/artist/skeezeball Aaron Rose is made into a video artist expressly because video and installation art require more viewer participation, which makes it “lazier.” From Aaron Rose’s ghost designer Nathan Nedorostek:

[H]is art was supposed to be very pretentious. With that we took the idea of this installation where he does video installation but there’s really nothing there, so what we wanted to do was have this idea that it was nothing he recorded, it was the viewers actually making his art for him.

You can tell a lot about what kind of show you’re watching from the way it treats art. Most TV shows distrust art, but every so often you’ll find a show that is really and truly optimistic: “Friday Night Lights” falls into this category, as does “Charmed” and sappy-happy “Dawson’s Creek.” Though the shows run the gamut of taste, all three programs confirm that art is complicated, but that’s okay. For example, imagine an exchange like this on a cynic’s show like “House”:

PRUE: So did the X-Ray confirm its authenticity?

JOE: It did a lot more than that. Check out the X-Ray. It’s got definitive underwriting on the canvas.

PRUE: It has a pentimento?!

JOE: Yeah, I couldn’t believe it either. But you can see it on the X-Ray. The text is in Latin! I’ve never seen anything like it before.

PRUE: [Reading painting] Absolvo Amitto Amplus Brevis. To free what is lost say these words.

JOE: Wow, you speak Latin?!

The pentimento turned out to be a spell attached to a haunted painted castle, natch. “Charmed”’s art-speak is laughable, but there’s nothing defensive here.

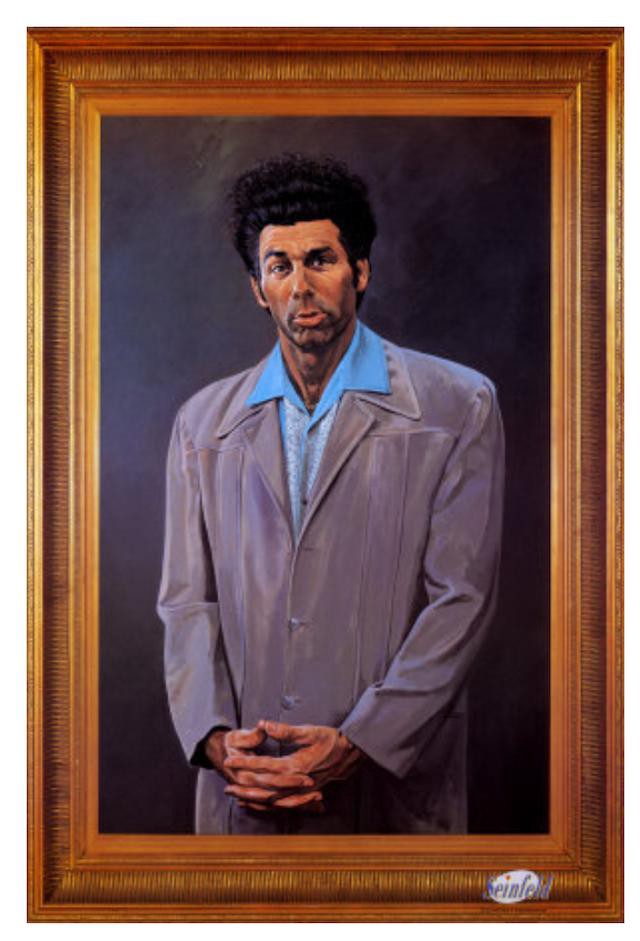

Compare that to a neurotic show like “Seinfeld,” whose most famous painting, “The Kramer,” is lauded only by the perversely indulgent.

“The Kramer”

MRS. ARM: I sense great vulnerability. A man child crying out for love, an innocent orphan in the postmodern world.

MR. ARM: I see a parasite. A sexually-depraved miscreant who is seeking to gratify only his most basic and immediate urges.

…

MRS. ARM: Dirty and unattractive, and yet I detect a nobility of attitude, an unwavering loyalty, much like the St. Bernard.

MR. ARM: But look at the eyes. He’s a creature barely hanging onto existence, like a cockroach clinging to a sewer crate.

MRS. ARM: He is man struggling. He lifts my spirit.

MR. ARM: He is a loathsome, offensive brute, yet I can’t look away!

MRS. ARM: He bends time and space.

MR. ARM: He sickens me.

MRS. ARM: I love it.

MR. ARM: Me too.

Besides “Seinfeld,” “Bones,” “SVU,” and “Vampire Diaries” all go in for “postmodernism” lolz. None of this is surprising. Postmodernism is pretentious? Artists are horny? Whaaaa?

But there are moments in which TV reveals itself to be a more adept cultural lens. When I first started this project I expected to find a lot of classic portraiture, abstract expressionism, photography, and still life. And I have. But I’ve also found installations, performance art, and mixed media made of strange materials. “Dexter”’s incendiary Lila West was not a scrupulous portrait of creativity, but her presence still acknowledged that fine art might be made of mannequins as much as oil paint.

Left: Screencap from “Dexter.” Right: IRL art featured at the Whitney. Specifically, it is “Don’t Touch Me (Oil Spill),” by Stewart Uoo (2012), represented by 47 Canal St.

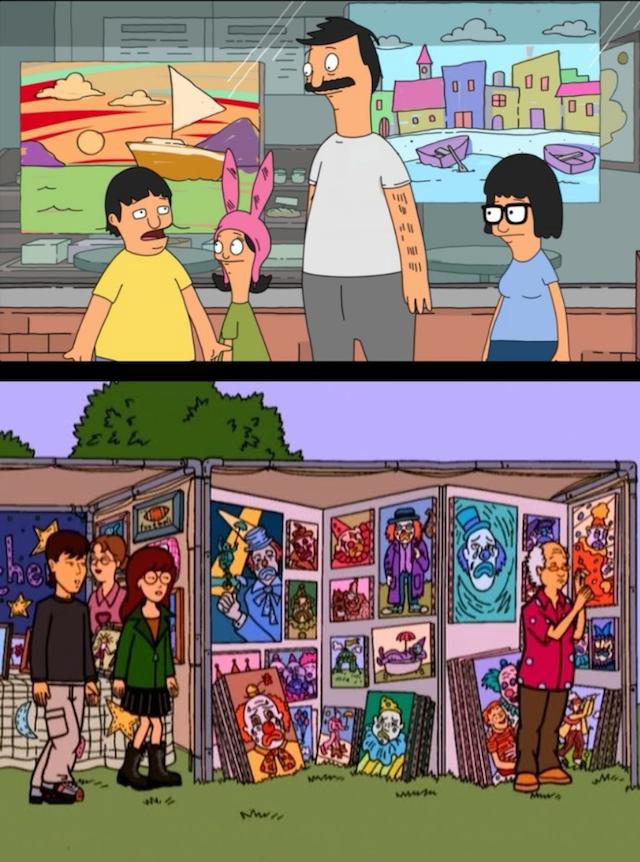

Several shows acknowledge the existence of (gasp!) kitschy commercial art, which I found on “Breaking Bad,” “Daria,” “Bob’s Burgers,” and, if we’re counting TBS-aired movies, Good Will Hunting. Although pop culture is invested in the tortured artist trope (one artist on “Bones” even wanted to die inside his sculpture), occasionally, prude commerce pokes through.

Cartoons do commercial art. Top: screencap from “Bob’s Burgers.” Bottom: Screencap from “Daria.”

Ab Ex still pisses us off, artists are tortured, PoMo is meaningless, the art world is for criminals and love bandits, everyone wants to get laid, and the shows you actually have to pay for have more realistic art. Bad or good, TV is an art education worthy of Hudson University.

Johannah King-Slutzky is awaiting her billion dollar grant to look at all this Law & Order art. Find her blog here or follow her @jjjjjjjjohannah. Found some good TV-art? Submissions welcome: artontv.tumblr.com.