How Has "Bust" Magazine Survived?

by Chris Chafin

BUST magazine operates out of a loft on 27th street and Broadway, above an awning that says Reiko Wireless Accessories. On the evening I visited, a bit before Christmas, young staffers rode up with me in the elevator, sharing swigs from a plastic bottle of whiskey. In the office they broke away, laughing and chatting, settling down at computers underneath walls covered in posters and stickers. One featured a giant image of Joan Crawford from Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? and the text “BUST Magazine says no wire hangers ever!”

The magazine’s editor in chief, Debbie Stoller, was in a state. She waved me to the conference room in the back, crowded with boxes of old issues and mis-matching chairs. “We have to overnight something right now!” she said.

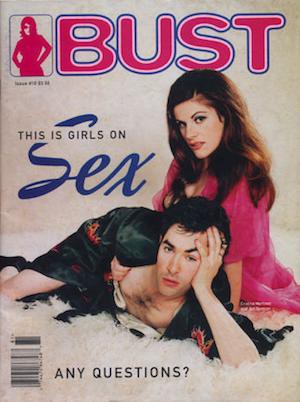

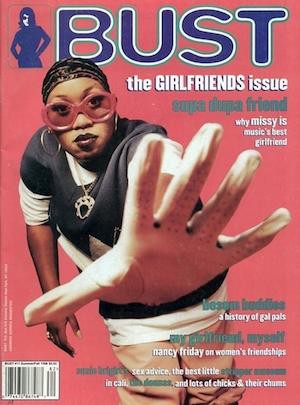

BUST celebrated its 20th anniversary in 2013. It’s a general-interest, celebrity-profiling magazine animated by a decidedly feminist worldview. It’s a sex-positive magazine for grandmas and teenagers that cares a lot about knitting and celebrities. Like many documents designed to serve an extremely wide audience of disparate people (Newsweek, the Constitution), it seems to perfectly serve no one.

It also inspires fierce loyalty. Kelly McClure, who was the magazine’s music editor for many years, tells a story about working the subscriptions table at an event when a woman walked up to ask if she could get a two-year subscription (all the signs were for one-year subscriptions). “I said no without even looking up, but then I saw it was Janeane Garofalo asking. I was like ‘I mean, yes! Whatever you want!’”

Christian Detres, who until recently worked in marketing and ad sales for the magazine, described the magazine as “the last woman standing.”

“If you want to talk about a feminist magazine that reaches young, creative women? There’s literally nothing else,” he said. How has a nervy, independent feminist magazine kept on into its third decade, in defiance of basically every trend in publishing?

Stoller founded BUST along with graphic designer Laurie Henzel and Marcelle Karp. The three of them were all working menial jobs at a fledgling Nickelodeon in the early 1990s. Stoller was in the typing pool, formatting scripts for teen ranch comedy “Hey Dude!” She was 31 years old and fresh out of grad school, having done her dissertation on “how the media influences women and how their representations fuck-up women’s heads.” She’d taken the job at Nick because she thought she’d be able to do some positive work, shaping the image of women on fledgling television network. Instead, she was typing up dialogue like the below, from the episode “Ted’s Saddle:”

MELODY: My name’s ‘Cool M,’ I work on a dude ranch. People eat so much you’d swear it’s a food ranch. They eat lots of eggs, they eat lots of butter — enough cholesterol to make your whole heart flutter.

BRAD: Mel, please… That’s awful.

Henzel and Karp were also less than engaged with their work. Henzel, a graphic designer who did cover art for her friends’ bands in her spare time, was slapping logos on things. Karp was working as an assistant in the promo department. “We knew it wasn’t what we were supposed to be doing,” Stoller said.

What they were supposed to be doing was a frequent topic of conversation for the friends. Eventually, they settled on the idea of a magazine. Not a zine, Stoller is careful to say, but a magazine, a rival to all the negativity and self-doubt of mainstream magazines for women (“The Nineties Man: Why is he so afraid of us?” wondered the cover of the June, 1993 Cosmopolitan). Even if it was black and white and run off on a copy machine, they all saw it as the early draft of a magazine and not the final form of a zine.

“In this day and age,” Stoller said, “you’d come up with a business plan, and think about how the thing would support itself and look for investors and think about who your advertising base would be and all that stuff. We didn’t think about that at all, and we didn’t care that much about it.”

Instead, they just thought about what was missing from the media landscape, their own personal priorities, and not much else. Their friends wrote the articles for free. To print the first issue, they snuck into Nickelodeon at night to run it off on the office copier and then hand-staple all 500 copies. For the second issue, they moved to the same Chinatown printer that published NAMBLA’s newsletter (everyone else had rejected them, thinking they were a porn magazine).

This may have been the magazine’s founding, but the true formative experience for today’s BUST happened around the turn of the century. The magazine published its first book, The BUST Guide to the New Girl Order, in 1999. It got the magazine a lot of attention, which happened to coincide with the first dot-com bubble. BUST quickly found itself courted by several media companies looking to buy them out, a prospect they were very interested in. “We had no idea how to make money in publishing. Maybe somebody else did?” said Stoller. They hadn’t paid themselves or their contributors for the entire run of the magazine up to that point — six long years of free labor. They were publishing irregularly, whenever they scraped together enough money to put out an issue. “When these guys came around, it was like, great, they can do the business part, and we could just focus on the magazine,” she said.

After several meetings, including one with Vice (who made a “very low” offer, according to Henzel), the magazine sold itself to Razorfish, an online media company owned by a friend of Henzel’s. “It was really clear that they got what we wanted to do, they were going to let us keep our jobs, they had no interest in changing things around, they had faith that we knew the right content to produce. So it was like, well, okay, this could work. We’ll have jobs and money and get to do our thing. It was like our dream,” Stoller said.

The dream was short-lived. As the dot-com bubble began to come apart, the owners of Razorfish became increasingly concerned about their money-losing media property. They decided to stop publishing BUST and look for additional investors. During this extremely precarious period, BUST somehow became the focal point of a New York Times story on the resurgence of feminist magazines. A photo of Henzel and Stoller that ran with the piece took up most of the front page of the Business section. “We got to the office that day, and the phones were ringing off the hook, and we were like, this is great, this is exactly what we needed,” Stoller said. She paused to give me a significant look. “You may have noticed that the article came out on September 10, 2001.” Razorfish’s stock cratered shortly thereafter, amid mass layoffs, and then was sold — leaving BUST officially out of business.

After much soul-searching (and a visit to a psychic), Henzel and Stoller decided to attempt to revive the magazine. This meant buying their name back from Razorfish. After a decade of running a magazine for free, they didn’t have much money to invest. As it turned out, it was only BUST’s total destruction and the general economic panic that followed September 11th that allowed it to keep going. “It wasn’t really worth anything at that point,” Henzel says of the BUST brand. “What could they do with it? They couldn’t sell it. They tried. Nobody was interested. We said, look, who else is going to buy this? Nobody.” In a friendly deal, Henzel and Stoller were able to buy back the BUST name for what they characterize as “the cost of a nice computer.”

Since then, its founders have run an extremely tight ship. It is owned in full by Henzel and Stoller. They carry no debt. They publish bi-monthly, and have a circulation of roughly 90,000 — about what it was in 2007. (In 2007, they had about 20,000 subscribers, and the rest was newsstand.) They have a staff of seven. They rely heavily on unpaid interns (proposed legislation that would abolish unpaid internships in New York is spoken about in the office in a terrified whisper). They all wear many hats: Stoller, for example, in addition to being the editor-in-chief, develops ideas for ad sales, manages subscriptions, staffs a subscription table at events, and, unless I misheard, seems to have played a very large role in building the existing website. “Debbie is very hands on with every aspect of the magazine. Unfortunately, she’s also very busy,” said Detres.

The result is that some of her projects for can languish, sometimes for years. The website can feel clunky and crowded to navigate; its toolbar has 14 categories. Stoller grimaced when she admitted that it hadn’t been refreshed since 2006. There are other opportunities — TV pilots, music events, and more — which the magazine is approached with or conceives of, but can’t follow through on because its small staff already spends all its time and money on putting out the print magazine. “Maybe we should find some investors,” Stoller said, and sighed. After nearly losing their magazine once, though, its founders don’t seem keen on giving up any control to anyone within their organization, much less outside of it.

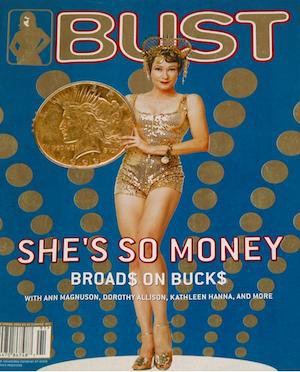

From its founding, a big part of BUST’s practice has been to look over the history of female culture, and trying to identify and promote things that have value. This has meant lots of coverage of traditionally female activities: jarring, cooking, knitting. This has lately resulted in a bit of hand-wringing and confusion among an even younger generation of feminists, who seem not to understand what BUST is up to. “BUST used to be a feminist magazine, but now it’s more crafty and about making things out of yarn,” Feministing’s Jessica Valenti told The New York Times back in 2009.

“When people say stuff like that, it’s a real bugaboo of mine,” Henzel said. “She means that yarn and crafts are ridiculous and wasteful.”

“If we all of a sudden had a section in BUST that was about sports — soccer, and ‘this is what women are doing,’ and women’s hockey teams, she would never have said that, because anything that comes from male culture is valuable,” Stoller said. “Anything that comes from female culture, is still, I think, foolishly rejected by a certain generation of feminists. They do it at their own peril, because you can’t just reject the culture that was of your ancestors and your history without having it reflect badly on you.”

The BUST brand is especially closely aligned with crafting: through coverage in their magazine, which is the work of Stoller. She is also the author of the Stitch ‘n Bitch series of crafting books, which have been popular enough to buy her a Brooklyn brownstone. They’ve found a way to monetize this with their Craftaculars. These events, running since 2005, are a sort of Etsy made flesh where hundreds of vendors fill a convention hall in Brooklyn, LA, Manhattan, or London and sell their handmade goods.

BUST charges vendors between $185 and $520 for a spot at their Craftaculars, depending on how much space they take up and how long they want to be there. A recent holiday Craftacular in New York drew around 300 vendors, which could have generated gross revenue for the magazine of north of $100,000. The magazine has hosted two or three Craftaculars each year since 2005. Henzel said they “wouldn’t be able to sustain the business” without them. Expenses for these events run high, however, and the magazine likely clears a relatively small amount of profit from them. Detres estimated that 75% of the magazine’s revenue still comes from ad sales, which he characterizes as being “a bargain” for brands. (The 2008 rate for a full-page ad in BUST was $6400.) One can take his assessment with a grain of salt, as it was his job until very recently to sell ads.

Toward the end of my interview with Stoller, I lobbed her a softball: “Why do you keep going?” It’s a question I ask a lot. I figure it gives whomever I’m talking with one last chance to draw together all the threads we’ve been discussing, and give a sort of “Law & Order”-style closing statement about why his or her non-profit or band or record label has meaning, and why it’s worth devoting his or her life to even if it’s hard and doesn’t have a lot of outward signs of conventional success. That’s usually the spirit in which people reply, anyway. When I asked Stoller, she looked at me for a long moment and then buried her face in her hands.

“I do think it’s fun,” she said, and sighed. “It’s something I can be proud of. For me, the only thing I think about is how the media is representing women. I’m always thinking about it. It’s fun to be able to work on something that’s in line with what I’m always thinking about anyway. Our staff is fun, it’s a fun place to work, a fun place to be. Sometimes I think, well what else would I do? I guess I could write more knitting books.”

I worried that I’d touched some bruise, or exhaustion point. I told her that I think what she does is valuable, that the magazine connects with people. She looked at me like she wasn’t sure I meant it. I’m not sure I did mean it. She walked me to the door, and grabbed a few copies from earlier this year. “Oh, here’s a few back issues,” she said. “Do you care? You don’t care. Here, take them, anyway.” I went home and ate dinner with my girlfriend and watched TV. Stoller went back to her desk.

Chris Chafin writes for a few places about things you can listen to, play or consume. Here’s his Twitter, which isn’t super compelling.