The Politics Of The Next Dimension: Do Ghosts Have Civil Rights?

by Matthew Phelan

An abridged version of this article first appeared in the October 1984 issue of The Atlantic Monthly as the cover story “The Politics of the Next Dimension: Do Ghosts Have Civil Rights?” It is republished here, in its entirety, for the first time.

For anyone with insomnia in the New York metro area, the ads have become ubiquitous: three middle-aged men dressed in cornflower blue lab coats, holding mysterious technical equipment, and offering the owners of haunted houses (or haunted anything, really) their unique ghost capture and removal services.

I first saw one after falling asleep to the dulcet drawl of Charles Rose on “CBS News Nightwatch.” The spot feels like a parody of those local commercials starring used car salesman and “crazy” warehouse owners. It ends with the team pointing their fingers at the camera, like Uncle Sam in an army recruitment poster, and shouting flatly over the din of passing traffic, “We’re ready to believe you!”

You may know of these men already. They’re the Ghostbusters.

Until the beginning of the current fall semester — when Columbia University abruptly shuttered its psychology department’s program in paranormal studies — Dr. Egon Spengler, Dr. Ray Stantz and Dr. Peter Venkman had been conducting research into extra-sensory perception and recurring manifestations of what they call vaporous apparitions and psychokinetic activity. “Psychics, ghosts, floating stuff, to the lay person. But to us it’s way more technical,” Dr. Venkman explains, half ignoring me as he rifles through the bottom drawer of a filing cabinet, then fixing me with a cold stare. “Stuff floats for a lot of different reasons.”

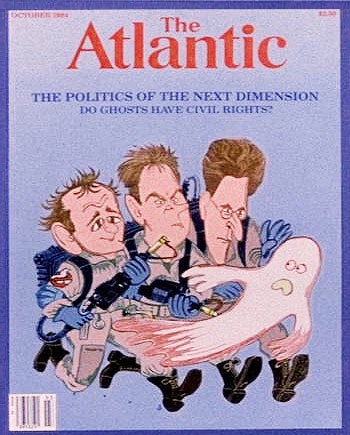

Our original cover, from October 1984.

“Dr. Spengler and Dr. Stantz are the only people I’ve seen who have taken all these parallel dimensions proposed by Bosonic String Theory and Superstring Theory, and are attempting to correlate them to supernatural events,” says Freeman Dyson, a theoretical physicist and mathematician at Princeton. “They’re the only ones actually gathering hard data on subatomic behavior during these unexplained occurrences — at the Ivy League-level anyway.” Notorious among colleagues for his contrarian streak, Dyson has avidly followed Dr. Stantz and Dr. Spengler’s articles in the journal of London’s Society for Psychical Research. It is outré reading material for a winner of both the prestigious Max Planck medal and the Harvey Prize, but Dyson is effusive in his praise for Stantz and Spengler’s felicitously documented case studies.

“[But] that third name doesn’t sound familiar to me,” he says.

It was Dr. Venkman, in fact, who lead the charge to commodify the trio’s academic research into a for-profit enterprise, talking Stantz into mortgaging his family home to purchase a headquarters for their business in lower Manhattan’s TriBeCa neighborhood. In just a few short months, the Ghostbusters have since rocketed to prominence, following a string of alleged successes in what they call the “reclamation of paranormal phenomena.” Clients, judging from press reports, have included a business at Rockefeller Plaza, a restaurant in Chinatown, the fashionable Manhattan night club The Rose, and their first widely publicized case at the five-star Sedgewick hotel.

Their service began to garner national attention almost immediately after the Sedgewick episode, with features on the Ghostbusters appearing in USA Today, Time magazine and a segment on Larry King’s late-night talk radio show on Mutual Broadcasting. Last month, they serendipitously acquired their own theme song, “Ghostbusters,” a Billboard-charting R&B; single by Ray Parker Jr., whose previous hit “The Other Woman,” coincidentally, also had supernatural elements. Occasionally, when the song is playing, the Ghostbusters will walk with a peculiar strut that looks bound to hyperextend their knees or trip passers-by.

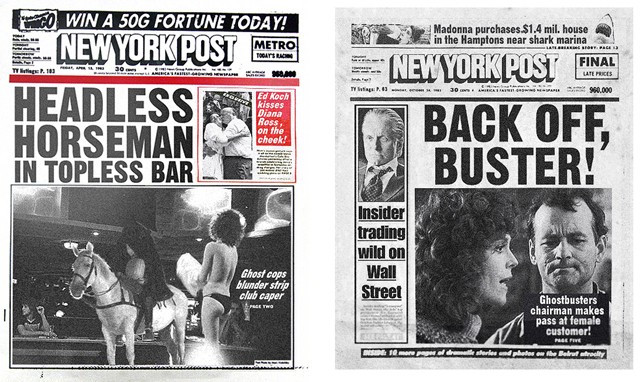

The Ghostbusters’ more infamous appearances in the New York Post. (Credit: Front pages for the October 11th and October 16th, 1984 editions reproduced courtesy of News Corp.)

Lately, this media attention feels like it’s sliding into mass hysteria, having already triggered a spike in ghostly sightings and haunted house cases across the country — and, as an obvious corollary, plenty of business for the Ghostbusters. But locally in New York their fame seems more qualified, occupying a liminal space between hometown heroes and objects of popular ridicule. Nowhere was that ambiguity more on display than earlier this month, when Venkman and Stantz appeared on “Beyond Reality,” a paranormal call-in show on Manhattan’s public access channel J, answering questions live over the phone and from the undead via Ouija board. Venkman, in particular, came off as ready to take the format into prime time. He sparred with crank callers — latter day Harry Houdinis looking to debunk the Ghostbusters’ televised séance — frequently insinuating their employment in various menial, degrading jobs while reminding them that his own labors let them work those jobs in peace.

“Did anyone have a grandmother named Iris?” Venkman asked the audience at one point, while manning the Ouija board with the show’s host. “She says you need to eat something.”

It was hard to tell if Dr. Stantz was being equally glib with me when I brought up this television appearance later. “I think it’s good for us to engage the public on Occult topics, but I recognize it’s an uphill battle,” he said. “Deservedly so, even. There’s every practical reason why Western Civilization has been stigmatizing this kind of esoteric knowledge for millennia: It’s immensely powerful, nasty stuff. Dangerous. Unpredictable.”

Having now pored over several out-of-print books on medieval demonology and mysticism on loan from Dr. Stantz, I’m still unsure how someone with advanced degrees in both psychology and physics could seriously entertain such a baroque spiritual cosmology. America has, of course, a long history in the thrall of pseudo-scientific, quasi-religious movements, from the Spiritualists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries to today’s Scientologists and infomercial televangelists. Are the Ghostbusters merely just the next wave? Or are they simply con-artists capitalizing on the moral panic created by the increasingly influential evangelical Christian movement, with its shrill warnings on the dangers of demonic possession, satanism and the always imminent “end of days”?

For their part, Stantz, Spengler and Venkman all refused to comment for this article on their rather lucrative involvement with both the plaintiffs and the defendants in the McMartin Preschool “satanic ritual abuse” trial. They were also equally silent when I asked them about a National Enquirer piece that claims Ghostbusters International had received payments via White House discretionary funds through First Lady Nancy Reagan and her alleged personal astrologer, Joan Quigley.

“I wouldn’t call them hucksters from my personal experience,” says Dana Barrett, a cellist with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. “I don’t know. It’s just sometimes hard to believe they were former college professors and not just former students.”

Barrett garnered some press attention after The New York Post learned that she had been the spectral reclamation firm’s first customer. (Barrett declined to elaborate on the nature of the supernatural occurrence in her apartment, but her neighbor Louis Tully told the Post that it was possibly a misunderstanding, given that “Dana leaves her television on a lot by mistake and, you know, it makes a lot of funny noises. There’s been complaints, but I don’t mind, personally. Dana’s great.”) The Post had a field day with claims that Dr. Venkman was ostensibly attempting to flaunt his credentials as the chairman of the Ghostbusters, “the largest paranormal investigation and removal company in America,” as a pretext to spending the night with Barrett in her apartment. Barrett has refused to comment on the Post story, but says she has retained the Ghostbusters’ services until her case is resolved.

It’s perhaps no shock given the firm’s ivory tower-pedigree, but coverage of the Ghostbusters in the Post has been remarkably adversarial, beginning with an early exposé on the negative aspects of the Sedgewick hotel incident. The ghost catchers had arrived at the Sedgewick at the climax of a bizarre, two week-long alleged haunting that was costing thousands in room service receipts, according to the hotel’s manager. Multiple patrons, the manager claims, had complained of a goblin-like apparition eating their food. A police report filed without charges by the hotel, but unearthed by the Post, stated that the Ghostbusters had destroyed a chandelier and much of the the Sedgewick’s main ballroom just minutes before it was scheduled to host the Eastside Theater Guild’s annual “Midnight Buffet.” Employees of the firm additionally scorched a stretch of wall down a twelfth floor hallway, according to the report, and nearly killed a member of the hotel’s housekeeping staff, evidently mistaking her sheet-draped cleaning cart for a ghost.

“They left me there trying to put out flaming toilet paper with a bottle of Windex,” said the maid, who asked not to be mentioned by name. “They said they were sorry, but didn’t try to help, at all. [They] nearly killed me! I think they’re assholes, to be blunt with you.”

The Sedgewick reportedly absolved the Ghostbusters of all responsibility for the property damage and the charges of reckless endangerment — as well as paying them a total of $5,000 for what many would consider the dubious service of removing a “focused, non-terminal repeating phantasm or a class 5 full-roaming vapor” (i.e. the food goblin).

Some clients, however, have been less charitable. Ghostbusters International, Inc. is currently listed as the defendant in one civil and two criminal cases in the tri-state area.

The first was a kidnapping charge brought by the descendants of two young women who had been tried for witchcraft in colonial Brookhaven and whose avenging spirits were now purportedly terrorizing teens at a Christian Youth Ministry overnight in Glen Cove, Long Island. The case was thrown out of Nassau County’s Tenth District Court when the victims’ 319-year-old death certificates were produced at a pre-trial hearing by Dr. Spengler, who for financial reasons has been acting as the firm’s legal counsel himself.

“Egon is a real Renaissance man and very dedicated to Ghostsbusting,” says the firm’s executive assistant Janine Melnitz. “And I think that’s very admirable, even though it doesn’t leave him much time for more personal, recreational activities.”

The second case pending against the firm, The State of New Jersey vs. Ghostbusters International, Inc., et. al., concerns a roughly 2,700-acre forest fire that the company is accused of starting in Wharton State Forrest while attempting to capture a legend of local folklore, the Jersey Devil, in the Pine Barrens National Reserve. Their client, prominent naval architect and owner of the New Jersey Devils hockey franchise John McMullen, is also listed as a defendant in the criminal complaint, which is scheduled to go to trial this February.

“My anticipation was that covering this trial would be a return to a region and a people that I’d come to love two decades ago,” says John McPhee who wrote about the arraignment in last month’s issue of The New Yorker. “Instead, it’s turned out to be a whipsaw return to the ghastly moral calculus of nuclear research, which I examined in my book on Theodore Taylor [The Curve of Binding Energy]. These Ghostbusters have essentially been operating cyclotrons — high-powered, particle accelerators — out in public with zero government oversight. Now, we know some of the risk factors here, because proton therapy has been a viable form of cancer treatment for decades, but no one, not even today’s leading lights in quantum mechanics, have practical experience with proton stream behavior at these flowrates.”

After the Glen Cove “witch” incident, McPhee says he spoke to physicists at Brookhaven National Laboratory who voiced concerns about Stantz and Spengler’s “proton pack” ghost catching technology. They likened the accidental intersection of these particle beams to operating a nuclear collider, or an “atom smasher,” out in the open air — multiplying the concerns that already swirl around this kind of high-energy particle collision research. In a telephone interview, Edward Witten of Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study confirmed McPhee’s anxieties saying that the theoretical basis exists for at least two doomsday scenarios: “Case 1. The Ghostbusters could accidentally create a microscopic, but stable, black hole that might begin accreting matter very rapidly, until Earth and its celestial neighbors were swallowed whole; or Case 2. The Ghostbusters could accidentally produce a bound state of quarks called a strangelet, which arguably could lead to a runaway fusion reaction reducing the planet to a large, smoldering orb of strange matter or a quark star. In either case, it would be pretty bad.”

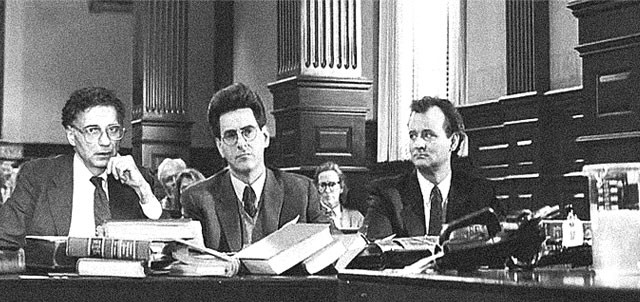

From left to right, consumer rights advocate Ralph Nader and Ghostbusters International co-founders Dr. Egon Spengler and Dr. Peter Venkman at a September 6th, 1984 hearing of the New York State Assembly’s Special Committee on Nuclear Safety. (Credit: Jeremy Ladd for the Albany Times Union)

When I broached this topic with Dr. Spengler, he said that while the Ghostbusters don’t normally discuss their proprietary technology with the press, they can say that SOP training has been implemented internally to mitigate the stream-crossing issue. He cited the firm’s voluntary appearance at the New York State Assembly’s Special Committee on Nuclear Safety in Albany this past September where details emerged of an independent audit on their facilities, conducted by Public Citizen, Ralph Nader’s consumer advocacy group.

“I voted for [Libertarian candidate] Ed Clark in the last presidential election and have had zero interest in voting either before or since,” Dr. Spengler told me as we sampled a chickpea-based Lebanese dish that Nader had left in the Ghostbusters’ office. “So it’s safe to say that Ralph Nader and I do not share much common ground, though I do respect his lack of sentimentality.”

The third and potentially most costly litigation facing the company is a class-action suit being pursued under the Clean Air Act by the Environmental Protection Agency. It began when guests situated above the Sedgewick Hotel’s main ballroom began complaining of a chlorine smell and a pale blue gas. According to the EPA’s lead investigator in the case, Walter Peck, there is considerable evidence from the Sedgewick and several others sites that the Ghostbusters’ spectral removal process generates ozone (O3) — a toxic ingredient in photochemical smog known to cause severe respiratory damage — at levels well above the limits set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Peck says the ozone-levels are of particular concern for clients in well-insulated spaces with low ceilings.

“It’s a ridiculous accusation,” Dr. Stantz says. “Any astrophysicist will tell you that proton streams from solar storms will routinely dissolve parts of the ozone layer. The whole reason our technology works is that these spectral manifestations are comprised of a negatively charged plasma. We are not causing these ozone levels, okay?”

“What Ray’s telling you is true,” Dr. Venkman added. “The ghosts are making the ozone.”

I made sure to broach this issue with Walter Peck in a follow-up interview. I also asked him what he thought was the legality of a private firm detaining someone’s immortal soul — particularly the souls of U.S. citizens as in the Brookhaven witch case — but he refused to entertain either of these ideas even as hypotheticals.

“I’d rather not dignify this confidence game the Ghostbusters call a business plan by openly discussing whether undead ghosts and goblins ought to have due process under the law,” Pecks says. “I don’t for a minute believe in these campfire horror stories, but irregardless [sic] the spectre of above-threshold ozone toxicity is very real. The basic fact is that three discredited academics are now out there, pointing dangerous, high-powered equipment at every creaking door and drafty window in New England. We need regulation and we need oversight.”

“He said that?” Dr. Stantz reacted with shock. “’Irregardless’ isn’t a real word, you know.”

“Frankly, there’s no accepted case law on the undead at the moment,” Dr. Spengler added, “but taking into account the inter-dimensional nature of these entities, I would argue that this is largely an immigration issue or a contraband issue depending on the sentience. Technically, INS should be deporting spirits of the deceased, as well as the other apparitions, the demons. We submitted a contract proposal, actually, but they haven’t responded.”

When this topic arose, I finally summoned the courage to ask the Ghostbusters about their containment unit, which Stantz, Spengler and Venkman led me downstairs to see. The ultimate spooky basement, the bottom floor of the firm’s TriBeCa headquaters is an ever-increasing summation of every other haunted basement in the world. Behind a phalanx of cautionary industrial signage, a red-painted steel casing, and an energy-intensive magnetic field, lies every spook, specter, apparition, ghoul and ghost captured by the Ghostbusters. Again: allegedly. Listening to the unnerving hum of the containment unit, I asked again about the ethical dimensions of corralling these seemingly conscious beings indefinitely within the company’s high-tech purgatory.

“We all feel kinda bad about the Sedgwick slimer,” Stantz told me. “After some of the hauntings we’ve witnessed in the past month, there’s definitely something endearing about a ghost whose only crime is maniacally pigging out.”

“He also smelled like onions,” according to Venkman. “I’m not letting him out of there.”

Few law scholars were willing to speak to me about the hypothetical legal issues of ghost entrapment.

Thomas Shaffer, who taught estate law at Notre Dame for 12 years, suggested I contact the Diocese of Rome’s resident exorcist Gabriele Amorth, but the priest declined an interview. One outspoken champion of Dr. Egon Spengler’s extradition and deportation analogies, however, horror fiction writer Stephen King, says he has spoken to Justice Department lawyers and others who were willing to support Dr. Spengler’s legal arguments.

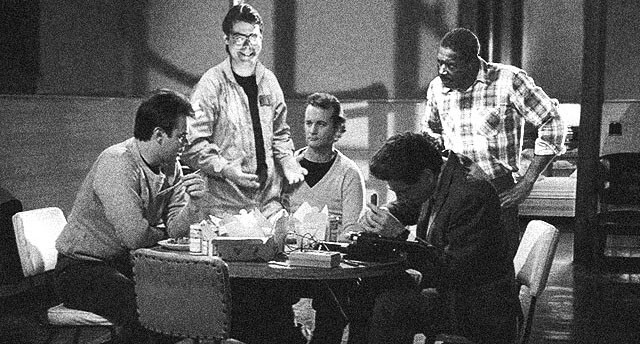

Horror author Stephen King, second from left, in 1985, the year after this article’s initial publication, dons a pair of official “ghost hunting” coveralls while trailing the Ghostbusters team. (Credit: Janine Melnitz, Ghostbusters International, Inc.)

“To a person, they’re all Reagan appointees or generally conservative in their interpretation of the law. One is a Lutheran and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court,” King said. “But they’ve all told me, off the record, that they could see this ‘inter-dimensional foreigner’ interpretation holding up, if a case were ever to go to trial, which frankly doesn’t seem likely. Personally, I think the argument would especially hold up in the Jersey Devil Pine Barrens incident or with a poltergeist — anything that’s not a former citizen and also possessing someone or causing physical damage is clearly engaged in a criminal act itself.”

King just recently signed a six-figure book deal, his first major foray into nonfiction writing, to chronicle the Ghostbusters’s exploits for Simon & Schuster’s Free Press imprint. Slated for release next September, King’s book, The Dehaunters, is being marketed as the first in a new genre: supernatural true crime.

“I’ve always envied those ride-alongs that crime fiction writers do with local law enforcement,” King told me. “This is my first time doing this kind of intensive procedural research for a book. It’s exciting. I’m still wrapping my head around some of the physics, but it’s been incredibly exciting. There’s something perfect about this business operating out of an old firehouse, with this pole and everything. I think we’ll live to see Ghostbusting as a genuine municipal utility.”

“I think Ray is the only one who’s genuinely happy that King is here all the time,” Spengler confided in me.

“It’s not that he isn’t a nice guy,” Venkman says. “It’s just that he’s way, way too excited. Sometimes, though, it’s nice that Ray has someone to talk about 14th Century Romanian magicians with — and he’s good at playing Star Gazer,” a pinball game on the building’s second floor.

Though King’s will be the first book to market, publishers are clearly banking on an increased demand for anything and everything Ghostbusters. John McPhee says he was contacted by pulp novelist Richard Bachmann, author of The Running Man and the upcoming supernatural thriller Thinner, about co-authoring a competing nonfiction project for the New American Library’s Mentor imprint. Tentatively titled Negative Beings, the book differentiates itself from King’s by focusing on the technical innovations behind the company’s flashy spook hunting.

“Bachmann is a strong science fiction writer and I’m a strong science writer. So, the hope is that we’ll be the first to resolve, for a popular audience, some of these outstanding questions about what the Ghostbusters do,” says McPhee who confided that he has not yet met Bachmann, but has been impressed by his written correspondence. “I can’t seem to get him on the phone, but I can tell Bachmann’s taking this seriously. I don’t want to stoke some literary feud with a top-selling phenomenon like Stephen King, but I think we’ll be making a valuable contribution with this second book.”

McPhee laughed off my questions about the ethics of Ghostbusting. “Who are you going to call? A lawyer?”

Cliches like “legal gray area” fail to adequately describe the terrain the Ghostbusters find themselves navigating, far out on the fringes of quantum physics and spiritual mysticism (ostensibly), and operating technology no one seems to understand. They’re off the charts — either wildly past the point of illegality, inventing new crimes and committing weird combinations of old crimes at a staggering pace, or positioned well beyond mere civic virtue at some superheroic point we may have to call sainthood.

It’s cold comfort given these stakes, but according to Bill Lauren, who is publishing an exclusive on the Ghostbusters’s proton packs for Omni, the team is at least routinely grappling with these thorny moral dilemmas in their downtime, even considering new ethical dimensions their critics have yet to broach: accidentally transporting clients to parallel dimensions, permanently ripping the fabric of space-time, catalyzing something called a “full protonic reversal” that they refuse to elaborate on and that no scientist I’ve spoken to has ever heard of.

“Just sitting in on the casual watercooler banter between them has been enough to give me nightmares,” Lauren confided to me. “You should ask Egon about the current Twinkie-to-Twinkie ratio.”

Around the office the Twinkie ratio has become sort of a gallows humor shorthand for assessing the increasing volume of “psychokinetic” (i.e. ghostly) activity in the New York-area, as compared to static levels. According to Dr. Spengler, the ratio is currently a Twinkie the size of a school bus. And it’s growing. The company is looking to hire and train new personnel to meet demand, but worry that they may have to start making some concessions to their own ideals.

“Up until now, we’ve been reticent to patent our technology simply because most of it has some disconcerting alternative uses,” Dr. Spengler says. “Dr. Stantz and I have already turned down two no-bid contract offers from the Department of Defense for strategic defense initiative research and some kind of death ray. We’ve felt that keeping our hardware proprietary for as long as possible was a great way to avoid regulatory overhead and keep the technology out of the wrong hands. But there’s a limit to the security we can afford to maintain that secrecy. And — especially if the Twinkie keeps getting bigger — we may have to form some sort of partnership with a state or federal bureaucracy.”

“That all being said, we are incredibly patriotic,” Venkman interjects. “Don’t forget to write that down. No one, nobody, loves this country more than the Ghostbusters.”

Oh, geez. Matthew Phelan has previously written things for The Onion, Inside Climate News, and Chemical Engineering magazine. (The cartoons and Photoshops were also by the author, fwiw.)He would like to thank two particle physics researchers, Dr. Peter Yamin at the Brookhaven National Lab and Prof. Sunil Somalwar at Rutgers, for reviewing this piece in advance. Obviously, though, if there is a mistake in the writing up there, somewhere, that isn’t just clearly made-up Ghostbusters stuff, then it is entirely and exclusively Matthew Phelan’s fault. Also, literally all of you should know that Prof. Somalwar helps run a nonprofit called Saving Wild Tigers that wouldn’t say no to donations; nor would the New Jersey chapter of the Sierra Club, where he is vice-treasurer.