Is the Internet Dying? Let's Go to the Cemetery and Pick Out a Tombstone

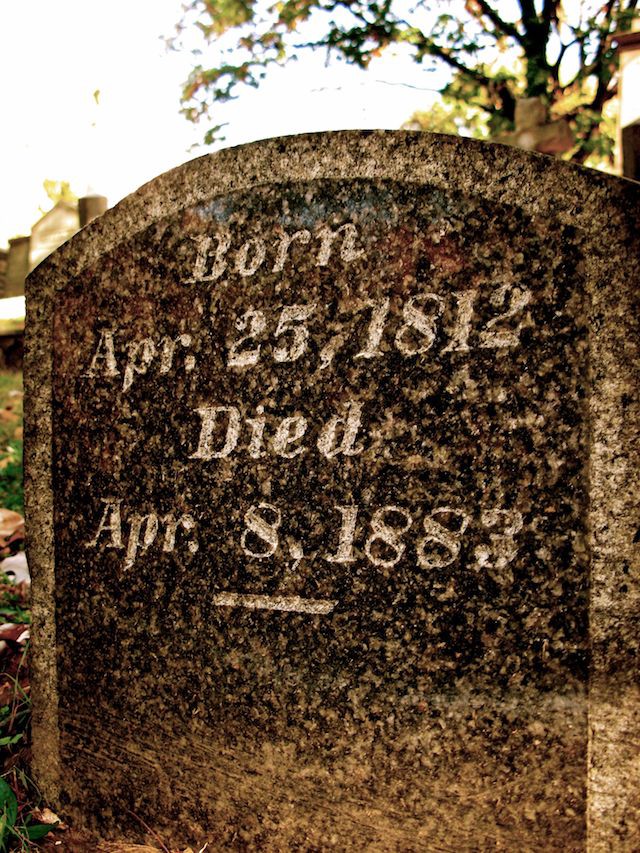

On a recent five-star November afternoon, I decided to visit Trinity Church Cemetery in northern Harlem. Starting at the plateau on Amsterdam Avenue and 154th Street, I followed the winding paths down through a kaleidoscope of autumn leaves and crumbling crypts, which, glowing in the western sun, appeared almost transitory. As one tends to do in cemeteries, I contemplated the end of all things. Lately, I had heard murmurs about “the death” of the internet, and though inclined to dismiss such speculation as a form of insipid nostalgia that often clings to any recollection of the past — and really, what is the internet if not an infinite collection of memories? — I wondered if there might be some truth to the idea. As I ran my fingers over the fading inscription of a tombstone, it occurred to me that, if the internet were really dying, we might inter it here, in this most beautiful cemetery in Manhattan, the last one on the island that still receives bodies of the dead.

Much as I sometimes would like to bury the internet, it only took a few seconds to conclude that any conjecture about its death was premature. We were not (yet) living in a television show about a future in which the electricity has been turned off, leaving a world full of surprisingly clean heterosexuals who wanted to kill each other. Most people still seem to read blogs — or web sites — similar to this one, and if you’re like me, you probably sent or received approximately 100,000 e-mails this morning alone. You may have even participated in a web-based meeting with employees of your company’s offshore vendor in China or India. For the past twenty years, the internet has been a vice of efficiency for the commercial trade of information and goods, and, as we all know, this part of it is not only alive, but also rapacious.

All logic aside, however, the internet still felt a little dead to me. I thought about G____ Reader and wished that a tombstone had been erected in the cemetery to mark its merciless execution. More than just a “feed reader,” G____ Reader had (to me, anyway) represented the blogosphere, the soul of the internet, that once borderless frontier now being relentlessly colonized by the insatiable corporate machines. So maybe blogging was dead, or close to it? It seemed possible. A few weeks earlier, as I was about to dispense my 86,794th heart on Tumblr, my soul hardened and cracked, leaving only a pile of ashes. It was not a bitter or tragic event. I would always consider Tumblr the best cocktail party I had ever attended on the internet, and didn’t regret the years I spent there, ranting, fighting, and LOLing with the wits and demagogues who made up its ranks. The site for me had fulfilled the premise of “social media,” and had done so in a reasonably “artistic” manner; I could fondly recall my dashboard, with its hypnotic photographs and gifs of flowers, ruins, breaking waves, and sun-drenched flocks of birds. (And, of course, as much porn as you could take.)

But I had gradually become incapacitated by the endless sales pitch of my online persona, the implicit dissonance as I compared it to my offline self, the constant cycle of posturing and affirmation. As I grew to know them, my fellow Tumblrs began to seem like family members — I needed a break! Or really, I needed a break from myself. If I sometimes felt like I was writing the novel of my life, it was one in which I had to send every sentence out to be work-shopped. I was beginning to hate myself; I needed to say goodbye.

There was something familiar about this departure — this tiniest and most subjective of deaths — which I realized had echoes in a decision I had made almost fifteen years earlier to leave Brooklyn, where I had lived for most of my twenties. In both cases, there was something unnerving about what I perceived to be bastions of oblivious youth and intensifying wealth. Together these elements seemed to create a stultifying atmosphere of conformity in which I — an aging, insecure, non-heterosexual pessimist — had felt increasingly estranged. But, thankfully, rather than languish in a self-constructed echo chamber of bitterness and self-loathing, I had left. It was better for me to quit, to escape, to start over in a place where I could realign my expectations about exactly what I could offer to my life, and what I could (and could not) expect in return. This process was now unfolding virtually instead of geographically; it made sense to me that the internet, given its ubiquity, is the only place of meaning you can truly leave anymore.

Because I lived just a few blocks away from the cemetery, I had often fantasized about spending eternity here, preferably on one of the hills with river views. One day, perhaps. I watched the sun sink into New Jersey and was consoled by the spectral wings of so many angels emerging from their crypts; they spoke in whispers barely audible above the rustling leaves. The internet, they reassured me, was not dying: I was, and, like everyone else, could soon enough expect to join this parade of the night.

Matthew Gallaway is the author of The Metropolis Case.