The World Is Full Of Trash

by Abe Sauer

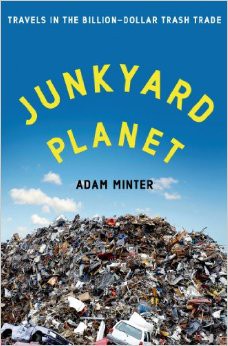

Adam Minter’s Junkyard Planet, new this week from Bloombury Press, is available from all sorts of places:

• Amazon

In addition, Minter is appearing tonight, November 13th, at 6 p.m. at the New School.

It’s a book one might call “a lifetime in the making.” For the last dozen years, Adam Minter has lived in Shanghai, writing about the global scrap industry, the fortunes it created, the lives and environments it’s ruined and how its fortunes paralleled those of the pre- and post-crash global economy. The result is Junkyard Planet, a one-of-a-kind inside look at the history and current place of the billion-dollar market for your scrap.

But more than just a junk journalist, Minter comes from junk; the son of a junkyard owner, Minter grew up watching the changes that reached from Guangdong to Houston to the front door of his family’s Minneapolis scrapyard. He longed to escape the industry that he’s still obsessed with.

The result is an infuriatingly enlightening story that will take a little cheer out of your tree’s Christmas lights while at the same time challenging perceptions about “garbage” as a singularly negative term. I spoke with the author in Shanghai about the book, China, and “growing up junk.”

The Awl: Riddle me this, junk man: why was I both depressed and encouraged by this book?

Adam Minter: Over time, I’ve developed a grim analogy to explain it to myself. Think of a terminally-ill patient who obtains a few extra months of life due to a high-tech miracle drug. On one hand, that’s really encouraging. On the other hand, there’s no escaping the inevitable.

It’s no secret that humanity is rapidly depleting the planet’s finite reserves of raw materials. Fortunately, there’s the recycling industry — the high-tech equivalent of a life-extending miracle. That’s the encouraging side of the equation. But no recycling process is perfect, and — in a sense — the recycling industry is just prolonging the inevitable reckoning for our mass consumption. As someone who’d like a guilt-free means of upgrading to an iPhone 5s, I find this all very depressing.

Does it ever boggle your mind as you cruise around Shanghai’s modern subway system, or between the city and Beijing at 302 km/h, that you’re doing it, more or less, in the garbage of your American peers?

I’ve developed a real interest in reincarnation, especially as it applies to inanimate objects. The power cord on my space heater? A previous life as a phone line in Wichita. The flip-flops I wear at the gym? The soles may have once insulated strands of Christmas tree lights in Duluth.

A few years ago I visited a pachinko machine recycling plant at the base of Mt. Fuji in Japan. It’s an interesting business. The average lifespan of a pachinko machine in a Japanese pachinko parlor is around three months; after that, the salarymen who play them every day want something new to dump coins into. Yet those same salarymen have very high expectations for the quality of their pachinko machines, and thus they’re built with the very best components, including super high-quality HD touchscreens.

So what happens to those touchscreens when they get to the recycling factory? They’re extracted, packed up, and shipped to GPS manufacturers in south China who — you guessed it — re-purpose them into new GPS devices that are then exported globally. In other words: it’s entirely possible that the GPS which helps you navigate a cross-country North American road trip may have once been responsible for the financial ruin of a Japanese accountant.

You’re what one (I guess only me) might call “old junk.” Your family was in the scrap business in Minneapolis. You also write: “[T]here’s nothing more enjoyable than sitting at a bank of video monitors with your grandmother and catching your employees stealing.” Really?

Recycling businesses, whether in Minneapolis or Shanghai, tend to start as family operations. My great-grandfather started out with little more than a backpack on the streets of Minneapolis, and over time he learned how to buy and sell waste. That’s knowledge he passed on to his children, who worked in the business, and that my grandmother passed onto me. I guess you could say that catching metal thieves was part of the syllabus.

As family heirloom knowledge goes, detecting scrap metal theft isn’t half as cuddly as making matzah ball soup, or speaking Yiddish. But what it lacked in romance, it sure made up for in hijinks. I was schooled by my grandmother.

This isn’t unique to my family. In Shanghai, I’ve noticed a lot of older women, fifty and above, working as roaming junk peddlers with young kids in tow. Every circumstance is different. But I’m pretty sure — this being China, and grandparents playing a big role in childrearing — those are grandmother-grandchild tandems. The lessons being passed between them probably aren’t much different than the ones that were passed through my family going back to the early twentieth century.

You write, “Until you’ve seen your first auto shredder, you can’t know.” When did you see your first auto shredder?

Can’t forget it. I was six or seven and my dad loaded me and a Taiwanese scrap dealer into his silver Cutlass and drove us over to North Star Steel in St. Paul. Then, as now, it was the only auto shredder and steel mill in the Twin Cities.

Anyway, we get out of the car in this dusty parking lot and I look up just as a flattened junker is dropped into the steaming maw of an auto shredder that — at the time — seemed like it was five stories tall. It was maybe half that. Then it happened again. And again. You have to understand, these machines were steampunk before anybody knew steampunk: massive, complex, steaming, tube and gear-encrusted devices built to fire the imaginations of seven-year-olds. So my dad tells me and the Taiwanese guy to follow him and we go around the back of the thing where fist-sized bits of metal are dropping from conveyors. Then I look back, and more cars are arriving. I was just flabbergasted.

What I didn’t know then, but know now, was that the Taiwanese guy was probably there looking for mixed metal fragments that he could export back home for hand-sorting into individual metals by the island’s (then) low-cost laborers. Ironically, the first Chinese scrap yard I ever visited — in 2002 — was a hand sorting facility for the kind of metal I saw flowing out of that North Star Steel shredder.

You describe some of the demeaning tensions at play between Chinese scrap buyers and American sellers. What is it about the scrap industry that gives it an old world commerce feel, like one might have imaged in the 17th century fur industry, or even the slave trade? Is it the subject matter — “dirty” garbage — or is there a genuine gallery of rogues element?

Nobody aspires to make a living sorting through other people’s garbage. Rather, people generally go into the trade because they lack other options. So, at least on the lowest rungs of the industry, it’s dominated by immigrants — illegal and legal, internal and international, the poorly educated, and those who face discrimination of some kind. Throw that all into a mixing bowl and you’re going to get a very bare-fisted kind of capitalism. And that culture persists, to a certain extent, even in economies where the scrap business has largely professionalized such as the United States.

I remember, one time, telling my great-uncle — a second generation scrap man, and the son of East European immigrants — that the scrap industry is the “boiler room of American capitalism.” He smiled at me and responded: “More like the sewer.” He’d done quite well in the industry, but he didn’t want his kids to have anything to do with it. And none did.

Maybe one of the book’s greatest triumphs is to make me interested in a whole chapter about things that happen in Houston. One specific detail is, despite ingenious technology in other areas, the headache that comes with sorting white polyethylene bottles from colored polyethylene bottles. Would reverse-engineering legislation to make recycling easier — like making only one kind of polyethylene bottle legal — stifle recycling innovations? Like with NASA, do we benefit from the advances in recycling technology without even knowing it?

The fact that Americans have such complicated stuff, and such diverse tastes, has driven pretty much every innovation in recycling technology since the 1950s. Cars are complicated and expensive to take apart; so technology had to be developed to do it. Likewise, red and yellow and white bottles are difficult to sort into their respective colors; so really complicated and technically sophisticated equipment involving infrared sensors had to be developed.

And this stuff is still being developed. So, yes, if Americans suddenly decided that — for the sake of the environment — liquids from salad dressing to bleach should be packaged in bottles made from the same gray plastic, it’d be bad for innovation. It’s odd when you think about it: we make complicated machines to clean up after our complicated products.

Everyone loves a caper and you talk a little about the grifts of the recycling business, like aluminum cans filled with rocks, something I believe I did in the 1980s, and the Chinese paper mill that “unpacked bales of imported American newspapers [and found] each stuffed with a cinder block.” What is the best scam of this sort you’ve ever heard about?

The guy in L.A. who had a hidden water tank installed beneath his truck. He’d go to scrap yards with loads of steel weighing a couple of thousands pounds — and hidden loads of water weighing two or three hundred pounds. I’ve heard different accounts of the weight. Anyway, trucks are weighed twice at scrap yards — when they arrive with the scrap, and after they’ve unloaded the scrap. The weight of the scrap for which they’re paid is the difference.

So this joker, he’d weigh-in with the scrap and the water, unload and then, when nobody was watching, he’d drain the water tank. Afterward, he’d weigh empty and the weight of the water would be added to the weight of the steel he carried. It made for a nice bonus. Until he was caught.

One of your points is that recycling as a business has gone on in the world since the first guy “beat a sword into a plowshare — and then tried to sell the plowshare.” So is America’s careless consumption of swords helping those who pound them into plowshares escape poverty?

What’s the cheaper way to get ten pounds of copper to make ballpoint pen balls? Dig a mine in Tibet, or hand-strip a pile of wire purchased from American electricians?

What’s great about the latter option, in addition to cost, is that it’s something that pretty much anybody can do. Whereas digging a copper mine is something that’s typically accessible only to the rich and well-connected. And that gets to the poverty-alleviating advantages of recycling: lots of people can start scrap businesses in lots of places. Mining? Some mines employ lots of people, but they tend to be very concentrated, geographically, and growth prospects are limited.

You note that plentiful America is the “Saudi Arabia of Scrap.” But actual Saudi Arabia and the Middle East get a mention too. What is the least wasteful developed place you’ve been?

Probably Tokyo. They have the money to buy and throw away lots of stuff, but the limited amount of space tends to make them very thrifty with what they have. Likewise, the Japanese obsession with quality means that they have a less disposable society than most developed economies.

When you took that first assignment to go to China and do a piece on the scrap business, you say you didn’t expect to stay for more than ten years. Do you know any foreigners who have been in China for more than even five years that expected to stay as long as they have?

Not a one. The question is, why?

Speaking for myself, I’ve found that China’s deepest appeal is to the accidental expat. Though there are exceptions, I’ve found that the people who moved to China always having wanted to move to China — and likely invested in learning the language before coming — tend to find their expectations are disappointed and leave.

Whereas the foreigners who stay are the ones who sort of stumble into a relationship with the place. For some people, the relationship-based culture that is China offers that kind of nutrition, if you will, and they thrive in it.

How has reporting on this often bleak subject — like the Christmas tree lights story — oh God, that story — changed your lifestyle over the years?

This Jew has yet to buy his first strand. But lord knows I’ve bought plenty of cheap products — electric razors to hot plates — with electrical cords that eventually went into a recycling bin or, yes, the trash.

To be honest, it was only during my sojourns in Chinese scrap yards, seeing the waves of American wastefulness turning up here, that I started to change my consumption habits. These days I do try to buy things that are designed to last, even if they cost me more. I’ve also become a big believer in buying refurbished products and products that can be repaired and upgraded. But I’ve been around this topic long enough to know that making a real impact means more than buying better-made luxury goods like smartphones. It’s a matter of reducing consumption overall, from hardback books to restraint takeout containers. Those are the hard steps and I’m not very good at them.

Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade is available now. Get it in Kindle form and save some paper. Adam Minter is also the Bloomberg View Shanghai correspondent and has written for The Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, Foreign Policy, The National Interest, Mother Jones, and Scientific American, He writes regularly at his blog Shanghai Scrap. He also tweets. All images above used with the author’s permission.

Abe Sauer’s latest book is “Goodnight Loon.” He is also the author of the book “How to be: North Dakota.” Email him at abesauer @ gmail.com.