Can We Interest You In An Opera Or Two?

Did everyone go to see Two Boys, Nico Muhly’s new opera, which will have its final performance tomorrow at the Metropolitan Opera? And if so, have you seen any other operas this season, or last, or ever? The reason I ask is that my internet feeds for the past month or so have been filled with an unprecedented number of updates from those who were inspired to wade into the operatic waters for the first time, which, for someone like me — who came to appreciate the form relatively late in life, and has spent my share of time trying to persuade skeptics to join me in this conversion — is exciting.

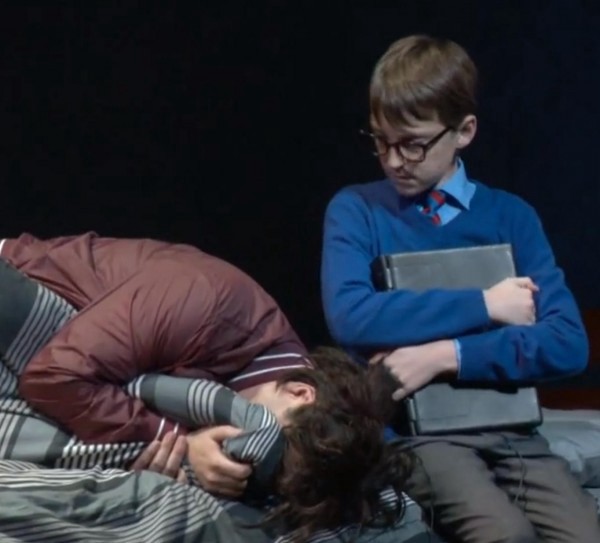

Even better, most who went (and were tweeting about it) seemed to love the show, and with good reason. The plot, which involves a mysterious murder and fake internet identities, was both easy to follow and suspenseful; I spoke to many people who were surprised (in a good, edge-of-your-seat way) by the ending, particularly in the racing second act. The stage was an interesting and very watchable combination of sparse “real-world” settings juxtaposed with projected computer screens, which often conveyed internet chats (and cams) as they unfolded in real time (but with singing). Most important, the music was beautiful, particularly the gorgeous choral scenes depicting the constantly mutating chaos that is (or perhaps “was”) the internet circa 2001, when the opera is set.

The opera felt very “alive” in the most literal of ways; it’s rare to go to the Met and see the composer bound up on stage to take a bow with the singers after the curtain falls. The audience was relatively young and very gay; a quick check of Grindr during intermission showed approximately 3000 men seeking hookups, all within fifty feet of the phone. (I’m exaggerating but only slightly.) That the opera featured actual webcam sex added to the sense that we were dealing with something very contemporary, but in the most artistic of ways.

Two Boys is at the end of its run, but let’s say that, after seeing it, or, we hope, planning to scarf it down tomorrow, you’re now officially intrigued by opera and want to know what to see next. My completely objective advice is to get tickets as soon as possible to Die Frau ohne Schatten (“The Woman without a Shadow”) by Richard Strauss, which still has four performances in the run.

I will admit to feeling some trepidation before I went to this one, on account of the fact that 1) the opera is long (four hours), 2) I had never seen it, 3) I had never heard the music, and 4) the synopsis of the opera made it sound impossibly complicated. I had just seen Two Boys: did I really need to go to another opera? I felt tired and lazy, apathetic; if the Metropolitan Opera was an old friend, I wanted to postpone our plans for a few months.

Thankfully I didn’t bail and, as it turned out, I saw something rare and transformative; leaving the theater, I felt like I had been immersed into a magic pool of water and been pulled out a different person, somehow new and improved.

I won’t get too deep into the story except to say that it’s about two romantic couples, the first a mortal Emperor and a quasi-immortal Empress (who needs a mortal “shadow” to have children and save her husband from being turned into stone), and the second a working-class husband (the Dyer) and his wife who are struggling, mostly on account of the wife’s frustration with her ongoing poverty and her dreams of a better life. The Empress descends into the working-class residence with the hope to entice the wife to sell her shadow in exchange for a life of glamour and passion. If it sounds complicated or far-fetched or convoluted, it’s really not; one of the great things about this production is that you don’t need to know anything going in; just sit back and listen — it all makes sense.

Like Two Boys, the opera — despite being almost 100 years old — feels very contemporary, especially during the scenes in which the Dyer and his wife argue, with him — good-natured but heartbreakingly naïve — counseling her to adopt an attitude of patience, while she lashes out at him in (understandable) frustration. The music in these scenes is impossibly tender, before it surges forth with a kind of raucous, stentorian fury that characterizes a handful of great operas by Strauss, who was equally comfortable with both lyricism and dissonance, often using both within seconds of each other. Frau also uses a gigantic orchestra, which in addition to providing wall-of-sound bliss means that the singers must have huge voices to be heard. With this cast, it wasn’t a problem; they were all astounding, and especially Christine Georke as the Dyer’s wife, whose voice seemed to gather strength as it rolled over the stage and broke over the audience.

The production is equally massive as it alternates between the two worlds, the upper realm a hall of mirrors and the lower — which rises out of the stage floor like some kind of mythic Gargantua as the music pounds — the decrepit, industrial apartment of the Dyer and his wife. The lights, also spectacular, regularly splay out over the audience like flocks of birds taking off over the sea.

Not knowing the opera before I went didn’t bother me at all (and shouldn’t concern you); if anything, it made me more vulnerable to its power, because I had no expectations about what it (or the singers) should sound like. I also thought about opera-goers 100 years ago, and how they probably went to the theater with little-to-no expectation to ever hear the music again. It was a relief to hear live music completely divorced from the digital reproductions to which we’ve all become so accustomed.

Like Two Boys, but in a very different way, Die Frau grabbed me by the shoulders and shook me out of the doldrums that so often threaten to define life, particularly these days when, if your life is anything like mine, it can feel like an endless, tedious scroll through an infinite Facebook. I have an old t-shirt imprinted with the slogan “LIFE IS SHORT/OPERA IS LONG” and after the performance, as I walked up Broadway to the 1 train, feeling somehow stunned and excited, as the flashing lights of the passing traffic seemed to continue the score, the words had never held more meaning.

Matthew Gallaway is the author of The Metropolis Case.