Williamsburg Before The Condos: The Soundtrack of an Unplanned Waterfront

by Daniel Campo

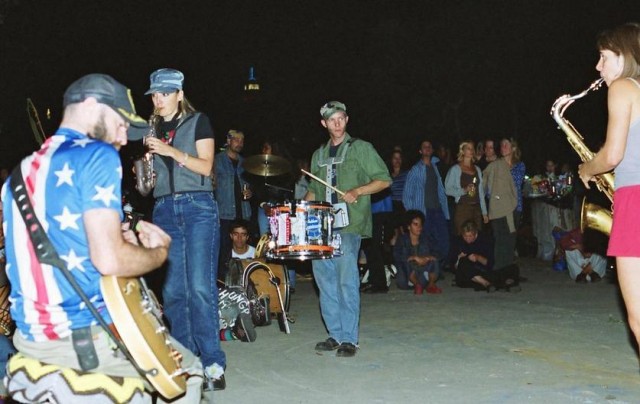

Few musical ensembles are so thoroughly synonymous with New York City’s underground scene as the Hungry March Band. Over the past fifteen years they have established themselves as the band that will play anywhere and everywhere, at any time and under all circumstances. Dedicated to “in your face” encounters with mostly unsuspecting audiences, they are a “public” marching band and frequently take to the streets with their instruments, whether they have been invited to do so or not. Once dubbed “Best Anarchist Parade Group” by the Village Voice, HMB gave performances on the streets, sidewalks, and subways of the city that are legendary. The band is large, loud, and unafraid to be heard, even if its presence leads to confrontation with police or arrest, which has happened a few times.

The Hungry March Band is not what you would typically find during halftime of a college football game. Their principal purpose has not evolved to support a team, honor soldiers and public servants, or provide musical accompaniment to yearly holiday ritual. They may indeed do these sorts of gigs, but the band is really more about making music, mischief, and the most of a good time. Their music also diverges from standard marching band fare. Playing mostly originals composed by individual band members, HMB incorporates a veritable kaleidoscope of source materials and inspirations, drawing upon the rich mix of sounds heard on the streets of the city. Sasha Sumner, a saxophonist with the band since 1998 and video editor and adjunct college instructor by day, described their music as “a big soup of influences and different styles,” noting its appropriation of Balkan, Latin, Klezmer, New Orleans jazz, Caribbean, Afrobeat, Bhangra, and European brass. Some have also compared the group to Sun Ra’s Arkestra, the revolutionary free jazz band. Their music is also part of the “Gypsy Punk” movement, a New York City–grown hybrid genre that the New York Times described as “mingling the passionate rage of Punk with the ragtag theatricality of traditional Gypsy music.”

The Accidental Playground: Brooklyn Waterfront Narratives of the Undesigned and Unplanned is available wherever one most enjoys purchasing books.

• Powell’s

• B&N;

Daniel Campo will discuss The Accidental Playground tomorrow — October 11th — at 8:30 a.m. at City Tech in downtown Brooklyn, and Thursday October 24th, at 7:30 p.m. at Hunter College.

When I first met the group, HMB had approximately twenty musicians and a few performers, which included someone who carried the band’s distinctive “ear plus crossed knife and fork” color guard. During the early 2000s they grew larger, and for some special events, Sasha said, they “customized” personnel to include more than fifty musicians, dancers, baton twirlers, and others. In the late 2000s, though, the band became smaller and their playing style became tighter. While still marching, members now often refer to their group as a “brass band,” which reflects its somewhat reduced size and more refined sound. At the same time, the group embraces its roots as a marching band and relishes its role in bringing this tradition back to the fore and popularizing it with young people. HMB has also inspired the formation of other marching bands, and ex-members have gone on to form their own eclectic ensembles, including the Rude Mechanical Orchestra, which has established itself as its own New York countercultural institution.

HMB has played block parties and festivals; rallies, protests, and fundraisers; loft parties and guerrilla art happenings; birthdays, weddings, and funerals; and all varieties of parades and public celebrations. They have played on rooftops and in basements; at Lincoln Center, Madison Square Garden, and a cardiologists’ convention in Washington; on the Staten Island Ferry and in the Mardis Gras parade in New Orleans. Closer to home, they have provided background music to New York City Marathon runners as they make their way up Bedford Avenue. Through the sheer volume and variety of events they have played, HMB has become emblematic of the city’s larger millennial underground of music, entertainment, and nightlife while evolving into ambassadors for the city’s creative scene through their travels both nationally and abroad and their recordings. When the band plays, people know that New York’s unique performance scene is still thriving and that gentrification has not swept away audacious street-level arts.

But countercultural fame and international renown gets the band only so far, and their lack of organizational affiliation, while surely liberating, has come at a price. Without a university athletic field at their disposal or an auditorium or gymnasium when the weather is poor, where can HMB practice? Over the past few years they have often rented time in a variety of indoor spaces, but finding space and time has been a constant struggle. For a while the Williamsburg waterfront was their rehearsal spot, and they practiced there most Sunday afternoons from 1997 until 2003.

One of my first intimate HMB experiences came on a chilly late October afternoon. I found Doug and Toto — a drummer and a cornet player, respectively — patiently waiting for the others to show up at their spot near the southwest corner of the Slab. The Slab was just to the north of the pier at North 6th Street and the L train’s ventilation shaft, at the foot of North 7th Street. The Slab — the former floor of a long-gone warehouse — and its surroundings eventually became the East River State Park, but first, it was a de facto people’s park.

I waited with them. Toto said the others would be there soon, but a half hour passed and still no one had showed. I asked if they were sure that the others were coming; had the session had been canceled? Toto reassured me — this was their regular practice gig; it had definitely not been canceled. The band had been practicing here every Sunday almost since its inception more than three years earlier. By 2000, coming down to the waterfront on Sundays was not something that needed to be scheduled; it was second nature, and band members came each week out of habit. The wind picked up and Toto, who was already wearing several layers of clothes and a ski cap, sought refuge underneath a Mexican blanket; Doug soon joined her. “I’m sure some of them will be here soon,” she said, a little less sure. After an hour, they too began to wonder, and Toto got on her cell phone and made a few calls. No one had canceled practice — rarely did someone take it upon him- or herself to make decisions for the entire group — but individual members they spoke to were not going to show for a variety of reasons. “I guess no one is coming so we’re not practicing this afternoon,” Doug told me matter-of-factly. He said to come back on the following Sunday.

This was the normal course of affairs for the band, and Doug and Toto had long come to expect this sort of inconsistency from their mates. In the middle of a rehearsal the following October, Sasha described some of the challenges they had in getting members out to both practices and gigs. While the band had twenty members back then, typical attendance on Sundays was often closer to a dozen at that time. Performances were even more problematic. “We haven’t been a full group for a while and we have been playing a lot of shows,” she said. “Whoever can make it, makes it.” For a show they played the night before, a Brooklyn loft party, they’d had only twelve. “We just played our greatest hits,” she said, adding that they were fortunate that their sound was enhanced by the band’s commanding perch on a mezzanine above the party floor.

As Toto reminded me later that fall, HMB was no one’s day job, and members often had to balance gigs against their work schedules. Late-night gigs were not very conducive to maintaining a conventional work schedule. Some of the more musically inclined had other competing (and paying) gigs that sometimes kept them from making it to a show, while others had to balance attending a performance that might not start until after midnight with personal obligations and, for a few, with family time. Four or five members of the group were unemployed, Sasha said at the time. While this did not keep them from coming to practice or a show, it may have dampened their enthusiasm for rehearsals.

HMB was formed in 1997 to march and play at Brooklyn’s annual celebration of counterculture and grand freak show, the Mermaid Parade in Coney Island. Its name refers to its “hunger” for authentic musical and urban experiences and is a play on the adage “Will play for food!” (which the band has done many times). Beginning with just a few people from the neighborhood, it was more of a concept than a musically adept ensemble. The person who dreamed up the band and its name, Dreiky, quit the group soon after its formation. At that time, its members mostly lived in the Greenpoint and Williamsburg neighborhoods, and a few more lived in the East Village a short subway ride away. They tried practicing at nearby McCarren Park, but it was too crowded and they found the activity around them distracting. “It sort of seemed like a free concert,” Toto said. Living locally, band members knew about the waterfront and the people’s park dynamic that unfolded there on weekends. At an earlier rehearsal, Theresa, a drummer and founding member who long served as the band’s publicist and webmaster, said, “Timmy wanted to come down here, so we just came down.”

Of original members, only three were left by fall 2001: Theresa; Timmy, who played snare drum with an attached cymbal; and Sara, the band’s baton twirler. With his muttonchop sideburns and old-fashioned cap, Timmy, perhaps thirty years old at that time, often played with a cigarette hanging out of his mouth. His sense of vintage flair and somewhat gruff demeanor transcended his more diminutive size. He was never interested in talking and often seemed annoyed with my presence, which he thought distracted the band from rehearsal. He was probably right on a few occasions, but many band members were given to distractions and if not me it might have been something else.

Another original member, a bit like Timmy in temperament but more outgoing, was Gam, the band’s mercurial trombonist. In his early thirties, he too he had a certain timeless charm to him, no doubt enhanced by his tendency to wear vintage-style caps and sleeveless undershirts. A local kid from the neighborhood, he was well familiar with the waterfront and often spent time there without the band. After his initial suspicion of me subsided, he became quite garrulous and talked authoritatively about the social lore of the waterfront and neighborhood. “Do you remember when there were raves in the warehouses here?” he asked. I had never attended any of the raves in the 1990s that several other people had also recalled. By the early fall he had dropped out of the group, though neither he nor any of his former band mates were willing to say why.

From its modest beginning, the waterfront was a good fit for the band and an excellent place for them to grow, eventually becoming the bigger, brasher, and more musically savvy ensemble they are today. Nobody seemed to mind their loud and sometimes raucous presence on the Slab. Sometimes when it rained they would practice in another co-opted neighborhood waste space, underneath the Brooklyn–Queens Expressway. When it was too cold they practiced in someone’s loft or basement, or not at all. Even as the area gentrified, there were still large studio, event, or live-work spaces available to them in Williamsburg or Greenpoint loft buildings that could serve as practice or performance venues. But the Slab was their principal rehearsal site, and their sound and identity evolved from their Sundays spent on the waterfront. “It kind of gelled once we got down here; the band wasn’t really together before that,” Theresa said. “Once we came down here — on Sundays — this [became] like our church, our religion so to speak. This is a very spiritual place.”

What was it about the Slab that made it so ideal for HMB? “It’s a free space, it’s got a nice view, and it’s available — and it’s in the neighborhood,” Doug said. In assent, a few of the others who were sitting around him repeated, “And it’s in the neighborhood!” Toto noted that “there’s very little hassle… that is why we like to hang and continue to come back.” John, a trombone player, said, “It’s a vibe. It’s the most conducive practice space.” And: “nobody bothers us,” he said.

Proximity, cost-free anytime access, views, and the lack of hassles were all important to individual members, but as an ensemble the setting also fit the tenor of their music: loud, free-spirited, unpredictable, and occasionally angry. Their sessions had an anarchic quality — in method and song — and the volume, volatility, and festiveness of their sound helped create the soundscape that would color other leisure experiences occurring across the waterfront. But those qualities of the terminal that were particularly advantageous to the band were time-based, suiting its idiosyncratic rehearsal routine, which blended practice with play and often unfolded over long afternoons. Without designated areas or constraints of schedule, they rehearsed, performed, and partied, in no particular order and often all at once. Rolling into and out of sessions, they moved freely between practicing and hanging out, ensemble and uncoordinated play, and played for as little or as long as they wanted.

On a typical Sunday, members collected themselves near the southwest corner of the Slab, often around 2 p.m. Those who arrived early (or on time) were not bothered by the lack of an immediate quorum with which to practice, and this waiting became a sort of social time. As a critical mass formed, some picked up their instruments and warmed up individually or in groups of two or three. As different members noodled on their instruments, being joined and left by others without apparent plan or consent, some of their mates, seemingly oblivious, continued to socialize. At some point and often without explicit cues, the entire contingent came together to begin formal rehearsal. But getting to this moment could often take a while, and sometimes it never really happened.

The end of rehearsals followed a similar pattern, though in reverse sequence. The music often devolved slowly, becoming more chaotic as more people broke off from the group to do their own thing, musical or otherwise. Sometimes the music just petered out, and by the time the last band member had stopped playing the others were well into “after-practice” beer-in-hand socializing or getting ready to light the barbecue. This was particularly true during good weather, and the Slab’s physical dimension and lack of social constraints accommodated these quick transitions to or from playing soccer or football and barbecues and parties. The looseness of these sessions was surely a reflection of the band’s idiosyncratic character, and most members knew to expect this sort of mild anarchy on Sundays. About the quality of rehearsal, John noted, “Sometimes it was marvelous and sometimes it was crap,” not sounding particularly bothered by the group’s lack of consistency. At times, though, some members were clearly frustrated with their mates who were seemingly determined to play solo or socialize.

Rehearsing the theme song from “The Muppet Show” in mid-October, a relatively rare non-original played by the band, provided a taste of this dynamic. A friend and I watched as Timmy tried to get the group together after what seemed like an unexpected break. “Okay, listen up! Let’s do this song,” he shouted, straining to be heard over the cacophony of talking and random sounds. “Let’s do this song!” He repeated as his frustration continued to build. “Enough talking, let’s do this song!” The band went through several starts and stops but did not have it together. Trying to get the various parts to harmonize, Timmy offered instructions to individual members and barked out the beats he expected. To demonstrate the proper tone and cadence, he sang a line from the song: “Why don’t we get things started?” He approached different members and repeated the line, and they sang it back him, attempting to match the requested octave and accentuations. “And with all the highs and all the lows!” he added. They did it a few more times. Twenty minutes later their final version was perhaps not at the level of harmony that Timmy had expected, but it did contain the appropriate amount of oomph — and entertained those of us listening and watching on.

As practice was breaking up, Sasha tried to better explain how these sessions usually worked. As we talked, Emily, another saxophonist, tried to corral her nine-year-old son, Sam, who usually attended the rehearsals with her, often banging a drum as they practiced or sneaking some notes in on the sousaphone while it lay unoccupied on the ground. Sasha, who wore a vintage dark coat with stripes sewn onto the sleeves (perhaps this was a genuine marching band coat?) and a similarly vintage cap, said the group had a “musical director” only for recording sessions, and there was no similarly designated role for practices. Different band members would sometimes attempt to guide the group, as I had watched Timmy do on that afternoon. “To accomplish something, it ends up taking a long time. But that’s the nature of a large group like this one — because people want to have fun,” she said.

I thought the session was over, but Theresa and Samantha, the band’s cymbal player, came over and smiled at us. “I think we’re gonna play one more song, special for you guys now, ‘Asphalt Tango,’” Theresa said. “It’s a really good song!” Samantha said. And with that they launched into a furious version of this Gypsy Punk number, a signature song of their early years.

The anarchy of space and sound — the waterfront and the Hungry March Band — went hand-in-hand and made for some lively if not always productive afternoons. “It was a lot of partying,” Sasha said, when I caught up with her several years later. Even when the band was “on,” these sessions often devolved into long, semi-structured jams in one key, she explained. (I too remembered and did enjoy these improvisational journeys, which were a prominent if not completely intended feature of these rehearsals.) She noted that there were few remaining band members from this period, and most had never experienced one of these rehearsals. The waterfront is now part of the memory and lore of the band: the crazy place where the band found its signature style and swagger.

Daniel Campo is Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at Morgan State University in Baltimore. Previously, he was a planner for the New York City Department of City Planning.